Noa Eshkol

Commemorating 13 years since Noa Eshkol’s passing, TLmag revisits Gunia Nowik’s personal journey to Eshkol’s historic home in Holon (Israel) which was – and still is – the center of collaborative study for the Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN) and Eshkol’s dance repertoire.

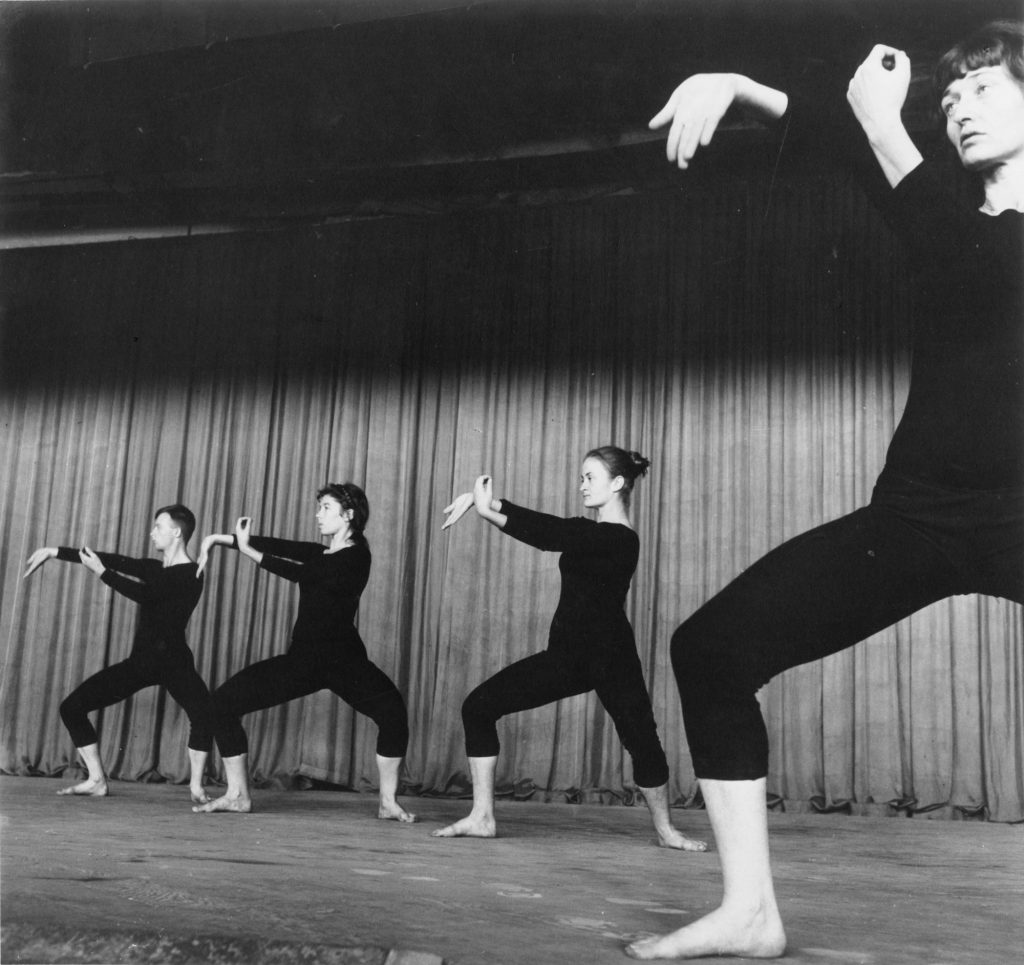

It’s a 20-minute bus ride from Tel Aviv to Holon. I get off at the bus stop, I find Arlozorov Street right away. Modernism, so captivating in the “white city”, is ubiquitous even here. There is a modest, elegant modernist house on the left. A metal gate leads to the garden. In the background, on the axis of the overgrown path, I can see a picture of a dancing figure. It is definitely here. Ruthi opens the door for me. Racheli is right behind her. Both dressed in black, ready for rehearsal. I don’t go into the apartment, because they immediately lead me upstairs, where they suggest that they dance to Noa’s notations. I sit on the sofa. Racheli turns on the metronome. There is silence and only that regular ticking. And the two of them, incredibly focused, dancing. Precise and flawless. Between the two compositions they say, “We’re not as young as we used to be, but we’ll try.” Ruthi Sela is 79, Racheli Nul-Kahana is 76. They have been dancing the Eshkol Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN) for over forty years. In the choreographic composition, their bodies first follow a single trajectory, then part a moment later and meet again in the precise rotation of their movements. Inscribed in invisible geometry, they never touch each other, even though they dance very closely together. The abstract, hypnotic, extremely disciplined form of dance opens for me a fascinating world of gestures. I hold my breath for those few minutes.

Noa Eshkol was born in 1924 in the Degania Bet kibbutz. She was the daughter of Russian Jews who emigrated to Palestine before World War II. Her mother, Rivka Marsha, was a teacher, her father, Levi Eshkol. was active on the political scene (in the 1960s he would become the third Prime Minister of Israel). When Noa was four, she and her mother left for New York, where Rivka taught Hebrew. In the early 1940s, they returned to Israel and lived in a small house in the city of Holon, just outside Tel Aviv. As a child, Noa took piano lessons where she learned about musical notation, and then she went to the Tille Rossler dance school in Tel Aviv. There, she first encountered Labanotation – a famous movement notation created in the 1920s by dancer, choreographer and dance theoretician Rudolf Laban. At the instigation of her teacher, who saw her student’s analytical abilities, Noa went to England to study at Laban’s Art of Movement Studio in Manchester, and then at Sigurd Leeder School of Modern Dance in London. In 1951, she returned home to Holon and focused on creating her own movement notation, experimenting with composition and starting to create a completely new, unprecedented form of dance. For the first time, she could test her research by directing performances accompanying the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the Lohamei HaGeta’ot kibbutz. Shortly afterwards, she founded the Chamber Dance Group, which performed short scores according to the emerging system of notation of movement, which she was working on together with the architect Avracham Wachman. The result of their research, the Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN), was published in London in 1958 and then presented as a revolutionary achievement in the Israeli pavilion at Expo’58 in Brussels. After that, the development of the Movement Notation became the meaning of the life for Noa Eshkol and her close circle of devoted dancers. The collective ethos of the kibbutz was present in the community life of the house in Holon, as well as in the scores Eshkol wrote. Choreographic compositions were never created for soloists – at least two dancers were needed for them to exist.

While the Laban system assumed that all the dancer’s possible movements would be inscribed in the figure of an icosahedron made up of a set of points that their body could reach – Eshkol imagined that the end of each limb was a point inscribed in a sphere. To illustrate this principle, she designed instruments (built by her student and dancer John Harries) – Orbits – to help understand the EWMN system and apply it in practice. Sometimes she gives the dancers a record of a never before danced composition, checking if they could read it and recreate it. Her goal was to improve the method that allowed for the most accurate and universal recording of movement so that the movement could be repeated in an identical way. The dancer may appear to us here as a robotic instrument which processes the record of movement in a mechanical way, but the instruments are, in fact, all parts of the dancer’s body, making them a one-person orchestra that needs human sensitivity and intelligence to perform the EWMN composition.

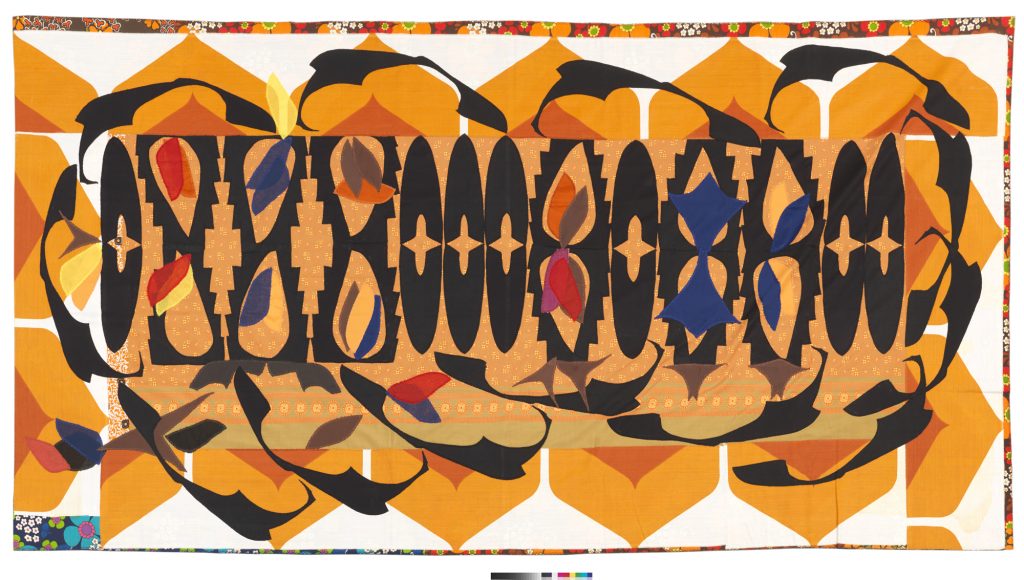

At the end of the 1960s, professors from the Faculty of Electronic Engineering at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, became interested in the EWMN system and invited Eshkol to continue research using the developing computer technology of the time. On this occasion, as an illustration of the system, the Chamber Dance Group gave several performances at university campuses in the United States as well as in London. Noa, however, never created her choreographies to gain fame and conquer the world, only to improve the EWMN system. She had not danced herself since the end of the 1950s, only keeping watch to ensure her compositions were perfect. She was opposed to the theatricalisation of performances and the creation of productions that were supposed to be so-called “shows”. Her several-minute scores were performed in silence with a regular ticking of the metronome, accompanied by neutral light. The dancers appeared in black, simple costumes that were designed not to distract from the precision of the presented movement sequences. The last performance of Chamber Dance Group in front of an international audience took place in 1972 at the Festival dei Due Mundi in Spoleto, Italy and turned out to be a revelation. Shortly after, however, Noa decided that she should focus only on working on the notation. Her isolation from the outside world was helped by a traumatic event in Israeli history: on 6 October 1973, the Yom Kippur war broke out. Noa always had a very close relationship with her dancers and one of the members of the group, Shmulik Zaidel, was mobilised to the Syrian front. Eshkol decided to suspend rehearsals until the dancer returned home safe and sound. It is then that she experienced her first choreographic crisis and, looking for an activity that would draw her thoughts in a different direction, she found old scraps of material that she started to compose on the floor, intuitively, in an empty dance hall. She engaged her dancers in the creation of what she called wall carpets. The dancers sewed her compositions together by hand and set out to look for scraps of materials thrown away near a tailor’s shop in Tel Aviv, or the Lodzia textile factory in Holon (named after the Łódź textile city in Poland). Friends started sending her fabrics collected in various Israeli kibbutzim; she also received military surplus blankets, which were often used as a support for new tapestries. As in the case of the work on the notation, Noa needed a system here, too, which she would stick to. The fabrics were thus segregated in terms of patterns or colours, they were never cut with scissors (so only the existing shapes were used), and those with the motif of a human figure were immediately rejected. She created tapestries that became her obsession until the end of her days and were obvious witnesses of the times in which they were created. Among their colourful – sometimes abstract, sometimes figurative – compositions, one can find characteristic fabrics from the famous Israeli Maskit fashion house.

We sit with Racheli and Ruthi in the kitchen at a big wooden table. The table very quickly fills up with Mediterranean delicacies served for brunch. Noa always sat at the head of it. They say they loved and admired her. For them, she was not only a dance teacher and mentor, but also an intellectual guide in life. It wasn’t an easy relationship. Noa had magnetism in her, but her character was rather difficult, and she required total dedication from her students. Not everyone could stand the pressure. Racheli left in 2000. She became too independent for Noa and even though they had previously understood each other without words, their daily contact with each other was unbearable. She went to therapy until she finally decided to cut herself off from the home in Holon and care for her own health. Ruthi’s fate was different, but she doesn’t regret her life choice. Raised in a kibbutz (like all Chamber Dance Group dancers), she moved to Nof Yam in the suburbs of Tel Aviv in 1966 with her husband and two children. Lonely (because her husband served in the army), she suffered a nervous breakdown. Her friends, knowing that she always loved to dance, recommended that she enrol in the classes that Noa Eshkol conducted in the Seminar HaKibbutzim. Returning home after each rehearsal, she felt, as she says, that she was floating above the ground and that her life was becoming meaningful. Four years later, Noa offered Ruthi a place in the Chamber Dance Group. At this time, her marriage had broken up and her husband decided to send the children back to the kibbutz. Ruthi didn’t go. Many people didn’t accept her choice, but she simply couldn’t do anything else but dance. She danced constantly until 2000, when Racheli left. Ruthi stayed with Noa until her death in 2007. She helped with the work on the notation and the wall carpet compositions, as well as keeping a diary of the activities of the Holon home. Years later, she rebuilt her relationship with her family. What she didn’t give her children, she gives to her grandchildren now. She keeps the journal to this day.

In 2007, after Noa’s death, Racheli crossed the threshold of the house on Arlozorov Street for the first time in seven years. Ruthi opened the door for her. They immediately knew that for years they’ve only dreamt of dancing together. They were moved. Their bodies remembered even the tiniest element of the scores. They were surprised that they were able to dance at their age alone, without Noa’s presence, in this fascinating world she created. The ritual of daily rehearsals returned, and the Chamber Dance Group was reactivated, welcoming new students and passing on the EWMN to the younger generations. Ruthi tells me with a smile, “I thought that with Noa’s death everything would end, but to my great surprise, it all began, and the world was open to us.”

I would like to thank Ruthi Sela and Racheli Nul-Kahana for welcoming me to Holon in October 2017, and Sharon Lockhart for initiating this visit.

This article was originally published in TLmag32: Contemporary Applied, and was uploaded on October 14th 2020 to pay tribute to Noa Eshkol on the 13th anniversary of her passing.

Cover Photo: Noa Eshkol holding two of her reference models, probably London, late 1950s. Image © Courtesy Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation, Holon, Israel.