Piet Stockmans: Porcelain Reincarnation

In this critical essay that traces Piet Stockmans’ oeuvre, cultural philosopher Willem Elias dissects the concepts and issues surrounding the influential Flemish designer and ceramist’s works.

This is not the first time Piet Stockmans has taken me to church to get me to write about his work, “Remember that you are dust and to porcelain you shall return” (installation 1999, Bergkerk Deventer (NL)). A biblically formulated paraphrase that, translated into the heathen language, coincides with the saying by Pindaros (518- 438 BC) cited by both Spinoza and Nietzsche, which translates into ‘heathenish’ as: “Become who you are!” Sartre taught us that this ‘becoming’ (existence) comes before ‘being’ (essence). Becoming, coming into existence, is not a flourishing nor a coming to fruition of what was already present in the nucleus. It is a contingent adventure, at the end of which a ‘being’ becomes apparent. In Piet Stockmans’ paraphrase, ‘dust’ represents ‘being’ (nature) and ‘porcelain’ stands for ‘becoming’ (culture). A beautifully formulated mission in life, for an artist. The use of a church or of a former industrial site as a space to display art is typical of our time. Modernism chose the white cube as its preferred space for presenting works from its of the purity of essences and its strong belief in neutral environments. Postmodern thought gave more weight to the various contexts and meaning-generating influences of environments on objects. Even more than any object like Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain’, an environment is a ‘ready-made’. It becomes even more interesting in artistic terms commensurate with its degree of realism. Especially when its reality already belongs to the past and is being sustained by historical awareness. Artists hardly belong in a computer shop, unless they are computer artists. The critical look at the intellectual platitudes broadcast by television, by Nam June Paik, the father of video art, was powerful precisely because he used discarded sets to create his installations. Modern art as an intrinsically slightly futuristic phenomenon has a staunch ally in the faded glories of the institutions of our daily lives. Having a history is the truth’s weakest point.

The Flemish saying “Scherven brengen geluk” (literally: “Shards are lucky”) would very likely be the common man’s reaction to some of Piet Stockmans’ works. While the archæologist would think: “Stockmans oeuvre is doomed to exist forever, as even in its broken condition it is perfectly complete art.” Neither the scientist nor the guy next door will realise that Piet Stockmans was to my knowledge – one of the first to demonstrate to us, at the very beginning of postmodernism, that the fragment in itself and as part of a series possesses aesthetic power. Its beauty is not per se its perfection. Besides, objects described as perfect are but fake-perfect, pretendentities that manage to hide the fact that they were manufactured at some point. This is what Stockmans demonstrates to us by presenting us with an imperfect fragment, created in his characteristic spirit of playful frivolity.

Which is not to say that no stage setting was involved, but in each instance, the disposition might as well have been different: ‘complete contingency of phenomena’, which is the basic concept of free thought and creativity: no constraints, nor any unpremeditated coincidences, just one tested possibility that welcomes alternative dispositions.

In a recent series, he proffers a variant of the aesthetics of the shard, to make us aware of the beauty of repairs. This is a known phenomenon in fashion, witness its – by now widely popularized – torn pants and patched denim clothing. In art, this not a familiar theme yet. The antique’s dealer will lightly tap an antique plate to verify whether it has any cracks or whether it has been broken and glued together. Piet demonstrates how beautiful repairs can be. ‘Repair’, from ‘reparare’, getting an object ready for reuse. In the case of Stockmans’ work, we could call this ‘recreation’; creating again, a repair that includes creation.

From ceramics to a theory of photography is quite a leap. Or is it? Art is looking and being looked at. The mechanical eye is also a metaphor for looking. In his La Chambre claire, Roland Barthes introduced the notion of ‘punctum’, which designates an element of the image that is not its essence, but fascinates the viewer more than the essence, because the essence is, in all, rather boring. The banality of tautology: a plate is a plate to eat from. But examining why we prefer to eat from the one plate rather than from the other is more interesting. What is the influence of Stockmans-blue (Stockmansblauw)? The punctum is often just one detail that jumps out. The popular expression is: ‘it catches – the eye’, thereby not causing blindness, but a visibility born of a longing admiration. ‘Punctum’ also means the dot on the dice – which allowed Barthes to smuggle coincidence into the concept. By diverting attention from the function of the ceramic shape and directing it to the construed repair of something that was never broken in the first place, a punctum-effect is created. Stockmans shuns false wholeness and wants to diversify, knowing that everything is fragmentary. Against the momentary intactness of a cast surface, craquelure will protest slowly by creating a network of cracks…

It is always remarkable how, in the middle of all this, Piet Stockmans manages to walk the tightrope between designing for industrial production and practising liberal arts. He never sets a wrong foot in this perilous adventure. His art is autonomous. The self (‘auto’) in this compound word is about his own creation, but the nomos (‘nom’) is not just about self-regulation, but also his relation to the rules of the game. In the art world, playing the games often means playing rough.

Though sacrality – re-sacralising in a heathenish manner at the desacralised church and profanely consecrating labour at the mining site – is a common thread throughout the exhibition, Stockmans’ work is the most in tune with the history of catholic liturgy. Daring to use the altar as a pedestal entails an overdose of Christian connotation. Stockmans’ work is sufficiently powerful to brave this. In all its ambiguity – the basic principle of modern art – his work refers to rituals and attributes: the relic (cracked clay pieces), the monstrance (is not every work of art a monstrance, an ostentatious displaying-while-obscuring?), the host, etc. If wearing chasubles were to be considered an option, the rite would probably turn into a black mass…

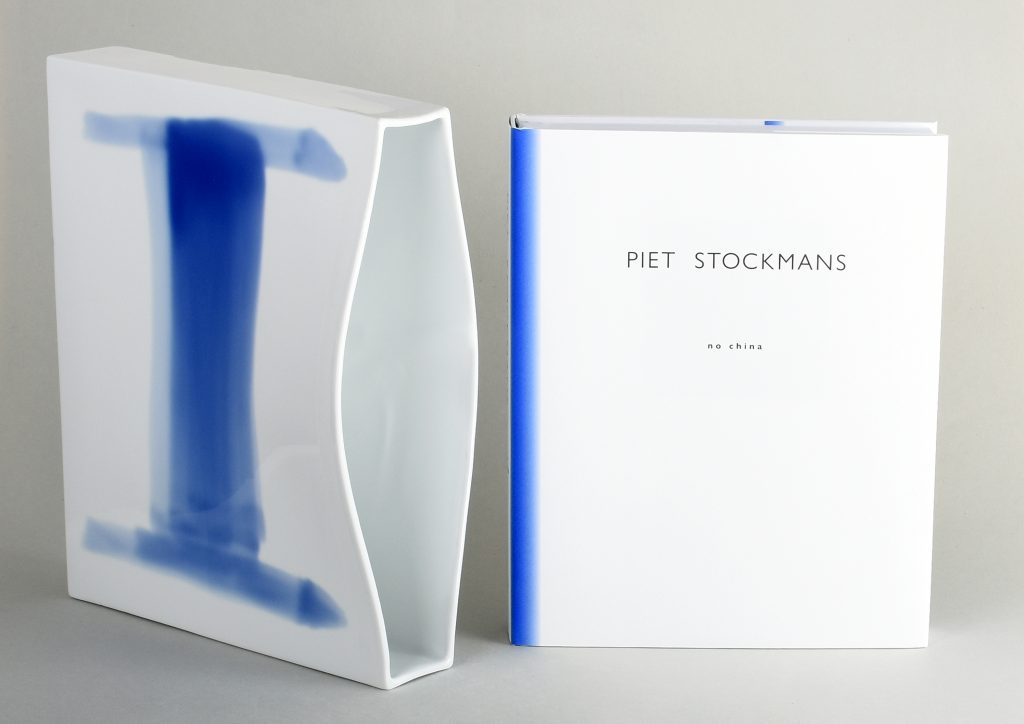

Cover Photo: ‘nageboorte’, creative process and installation, Thor Central, Genk, 2018

This essay was originally published in TLmag’s 2018 Autumn-Winter edition ‘Archæology Now!‘

www.pietstockmans.art

@studio-pieter-stockmans

www.spazionobile.com

@spazionobilegallery