RE/STORE: Aimé Mpane & Jean Pierre Müller

A collaboration by two very different artists challenges the stereotypes and stigmas embedded in an historic institution, underscoring the vital importance of revisiting the atrocities of the past to change the narrative and pave the way for a better future.

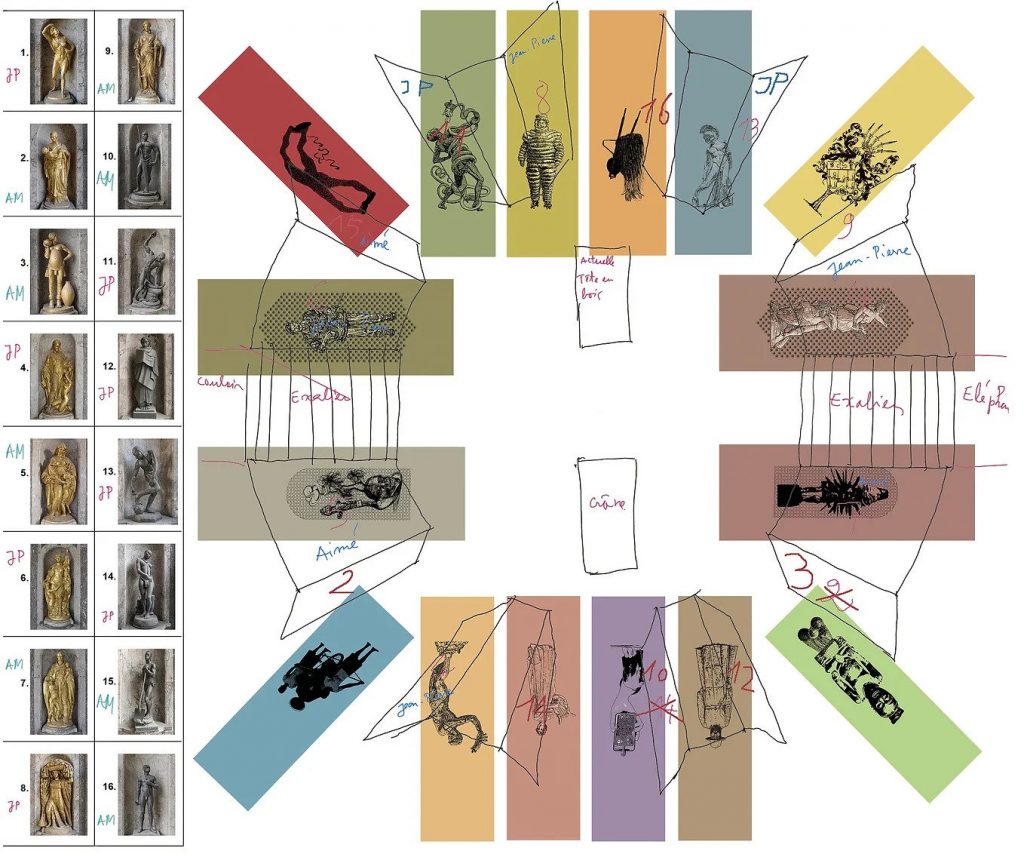

The Royal Museum for Central Africa was founded in 1898, but its current building was inaugurated in 1910 and is characterised by many symbols reflecting the colonial propaganda of the time. The grand rotunda, designed to serve as the museum entrance, plays host to a series of statues that are strong examples of such imagery, reflecting fundamentally racist stereotypes. Between 2013 and 2018, the RMCA underwent a major renovation that saw a substantial redesign of the permanent exhibition, with the involvement of members of the African diaspora in Belgium. A major challenge of the renovation was to demonstrate the will to decolonise a listed building that is legally protected against changes. As removal of the colonial statues was not allowed, the museum was forced to find innovative solutions, notably by inviting contemporary African artists to create installations to dialogue, contrast, and discuss with colonial messages.

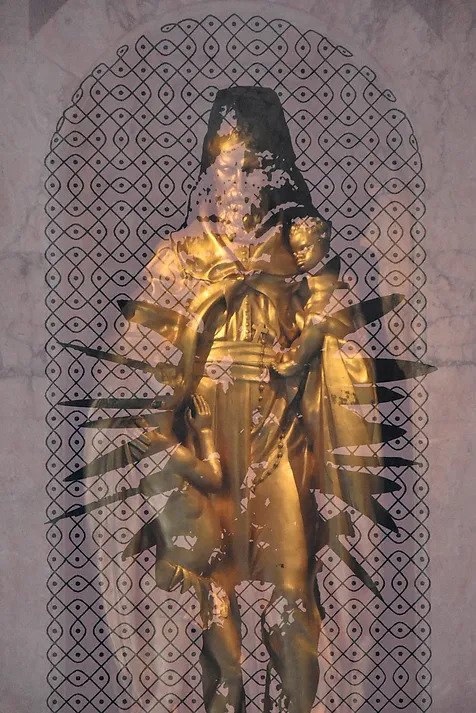

Congolese artist Aimé Mpane was chosen to make such an installation in the rotunda in 2018 with New breath, or Burgeoning Congo. Public reaction helped the AfricaMuseum realise that it needed to go further. Along with the creation of a second sculpture, Aimé Mpane, in co-creation with Belgian artist Jean Pierre Müller, proposed the RE/STORE project: a permanent installation of transparent veils, each bearing a contemporary message, hung in front of every statue in the rotunda. The themes addressed in this collection of veils interact with the viewer in a powerful and eloquent manner.

The following interview originally appeared in the book: “The Grand Rotunda of the Royal Museum for Central Africa”, 2022, edited by Aimé Mpane and Jean Pierre Müller.

M.F. Dubois: Aimé Mpane, how did this project with the AfricaMuseum begin?

Aimé Mpane: The museum launched a call for projects in 2016. I sent in my proposal, like the other artists, and the selection committee picked my installation New Breath, or Burgeoning Congo.

M.F.D.: What was your reaction when the UN Working Group asked for a reworking of this space in the grand rotunda in 2019?

A.M.: I had not been totally satisfied as my original plan was to have a larger sculpture in the rotunda’s centre. In its final form, the sculpture was not enough of a riposte to these sixteen historical sculptures. When the museum asked me to revisit the project, I had the urge to install a second sculpture across the first one. The idea of Lusinga emerged rather naturally.

M.F.D.: Then you invited another artist to join you for the project. Why?

A.M.: It came to me when I was thinking of the collective unconscious. These traumas affect all of us. I wanted to invite a Belgian, who would also be unconsciously bearing this burden. My project for the AfricaMuseum is not based on an idea of revenge. Rather, it strives to restore human dignity. When I speak of human dignity, I have current events in mind. Young Africans do not see their future. And a significant number of young non-Africans see the mistakes and cruelties of the past and feel traumatized. It is on the level of psychogenealogy. My project attempts to marshal the ideas and strengths of the youth on both sides, not to destroy, but to build. It is a positive project.

M.F.D.: Why Jean Pierre Müller?

A.M.: I met Jean Pierre and discovered his work through La Cambre. He already worked on these themes and I liked his aesthetic. I thought he could bring something to the project as a visual artist.

J.P.M.: We have known each other for a long time, but we only really started discussing projects a few years ago, mainly to set up a horizontal dialogue between students of Beaux-Arts in Kinshasa and La Cambre in Brussels. And then, during an atelier visit in 2019, Aimé brought up the issue of the rotunda.

A.M.: I told him about my concept of restauration and my idea of partially hiding the sculptures. Jean Pierre took the word in English and cut it in two: ‘RE/STORE’, which naturally became the title of our joint intervention. It places the emphasis on the word ‘store’: like a warehouse, an existing stock of images that can be drawn from. A universal heritage, in a way. Jean Pierre was able to make the project his own. He brought a new energy to it.

J.P.M.: Aimé was the one who invited me, not the museum. He took a risk, one that could have gone badly. In suggesting that we share the burden of this tragic legacy, Aimé made a strong statement. Primo Levi explained just how the inhumanity of the perpetrator led to the dehumanisation of the victim, both finding themselves shut out from what it is to be human. As descendants of the actors in this drama, can we stand together and look this violent past in the eye? And in doing so, rehumanise not just the descendants of the victims, but those of their tormenters?

M.F.D.: How did you end up with the veils?

A.M.: I wanted to remove the sculptures from their niches, but it’s important to keep these witnesses of history. I thought of turning them around, of planting ivy that would cover them, of sculpting bas-relief wooden shutters that would be left half-open. I like the idea of concealing and revealing.

J.P.M.: It was while discussing these possibilities that we arrived at the printed veil. It recalled certain things that Aimé already had in mind without being aware of it. Fabric, printing, transparency were already at the heart of my practice, so things just came together.

A.M.: I often work with transparency, even in my sculptures. In the 2000s, I had already made sculptures with veils.

M.F.D.: How did you split the work?

A.M.: There were sixteen sculptures, so we divided them, eight per person. We worked together on the four central pieces. To set them apart from the others, we put eyes in the background. Jean Pierre drew figurative eyes, and I took inspiration from African culture. These eyes watch you, observe you from all over. History watches and interrogates us.

J.P.M.: We also added borders at the bottom of the veils to expand the content. It is important to broaden the context and not simply limit it to the specific case of Belgium and Congo.

A.M.: These friezes are like an exquisite corpse, a duet. They are also nods to memory.

J.P.M.: They call on the viewer’s investigative abilities.

M.F.D.: What was your creative process?

J.P.M.: Aimé and I work well together, we like to follow and untangle threads. In RE/ STORE we found our respective obsessions: classical antiquity in my

case, precolonial Congolese civilisation in his, and for both of us, the question of language and etymology. One can see from my interventions that I am an artist- printer, because I play with the principle of superimposition: another figure of the same proportion is superimposed on a human figure. Meanwhile, Aimé is clearly a sculptor in the way he creates composites and associates several elements. This gives his interventions a more enigmatic character than mine have, and a welcome breath of poetry.

A.M.: I also trust my intuition above all. I followed my initial idea and took parts of the body: legs, skin, hair, genitals, hand, torso. For other veils, I adopted the principle of ‘store’ and selected objects that recall African heritage.

M.F.D.: What relationship do you have with the historical works in the rotunda?

J.P.M.: After having been confronted with them for several months, I can attest to the unbearable weight of the violence contained in these sculptures. Yet despite the rage, our interventions have nothing to do with issuing a definitive condemnation. It is not a question of retrospectively putting previous generations on trial. History is complex and our perception of it evolves. A work of art is the reflection and testimony of an era and the mentalities driving it. It would be odd to deny that a work carries the zeitgeist of

its time, both its genius and horror, and to confuse aesthetics with ethics. It is just as absurd to want to erase these testaments because they no longer meet the dominant standards of the moment.

M.F.D.: What does RE/STORE offer?

J.P.M: The preservation of contested works, the refusal to negate them and the consideration of the fact that they embody harmful symbols. We can see in RE/STORE the present addressing the past.

A.M.: I approach the statues of the rotunda the way I approach the day-to-day, because these clichés and stereotypes abound and follow me everywhere.

M.F.D.: The associations you made can be surprising or disturbing. What led you to these representations?

J.P.M.: I found it necessary to make references to rubber and severed hands. Dialogue is impossible without at least an acknowledgement of historical fact.

A.M.: Admitting wrongdoing can be violent and therefore dialogue must be induced to resolve problems.

J.P.M.: The world that saw the genesis of RE/STORE will change as well, hence our insistence on the versatility of both material and process. We can imagine that in a certain future, other veils (or megagalactic water- repellent vibrations) will hang in front of ours, examining our intervention.

M.F.D.: One of the criticisms levelled against museums is that they assuage their consciences and foist their decolonisation mission upon artists, especially ones who are African or of African descent, by calling on them for contributions. What are your thoughts on this?

J.P.M.: These sixteen pieces will not absolve anyone but at least they open a dialogue.

A.M.: Yes, it is a matter of dialogue and restoration. We show that there are ways of getting along, of forgiving, of being on equal footing and moving forward together. As Jean Pierre often says, we are using history as a medium.

J.P.M.: We are not historians, activists, or politicians. We are artists.

A.M.: We are not representatives of the museum either. We contributed to the museum as artists.

M.F.D.: Should the initiation of such dialogue take place in an institution like the AfricaMuseum?

A.M.: It is the ideal place. That dialogue needs to start here, not elsewhere. Culture, paradigm shifts, they happen through institutions. In an art gallery, it would fall into oblivion after a few months. In a permanent exhibition, it leaves a mark and is transformed to memory.

J.P.M.: This grand rotunda was to be the emblem of the Leopoldian enterprise. It could henceforth serve as a forum where one dares to confront experiences and emotions.

May the dome become a palaver tree! A place where those nostalgic for a paradise lost would cross paths with former heroes and rescuers of hostages, where artists riddled with doubt meet descendants of those who were humiliated, exploited, denied of their humanity, their bodies and their lands for so long. Their tales would mingle and intertwine, and listening to one another would bring a measure of peace. We could then envision together the restoration of a common heritage that, although damaged and in distress, will be irremediably shared. RE/STORE.

@mpane.aime

www.jeanpierremuller.be

www.africamuseum.be