Sammy Baloji – Stories Found in Copper

On May 20, Sammy Baloji was awarded a special mention in the Venice Architecture Biennale for his three-chapter project in collaboration with Twenty Nine Studio, which addresses the dematerialisation of the landscape and the delocalisation of precolonial social systems through colonial action. TLmag reposts an interview made with Baloji in 2018 for TLmag29.

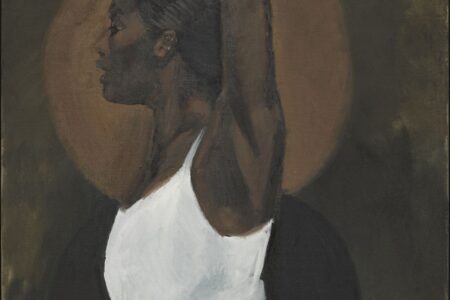

Since the mid-2000s, Sammy Baloji has been using photography, in part, as a means of tracing time — exploring the pre-colonial past of his native Congo, the impact of the colonial era, as well as post-colonial, contemporary society—with all of its complexities and transformations. Using documentary and archival images layered within his own photographs, he constructs powerful imagery that fuses past and present, re-examining historical legacies, while also revealing a society and country that remains little known to much of the world.

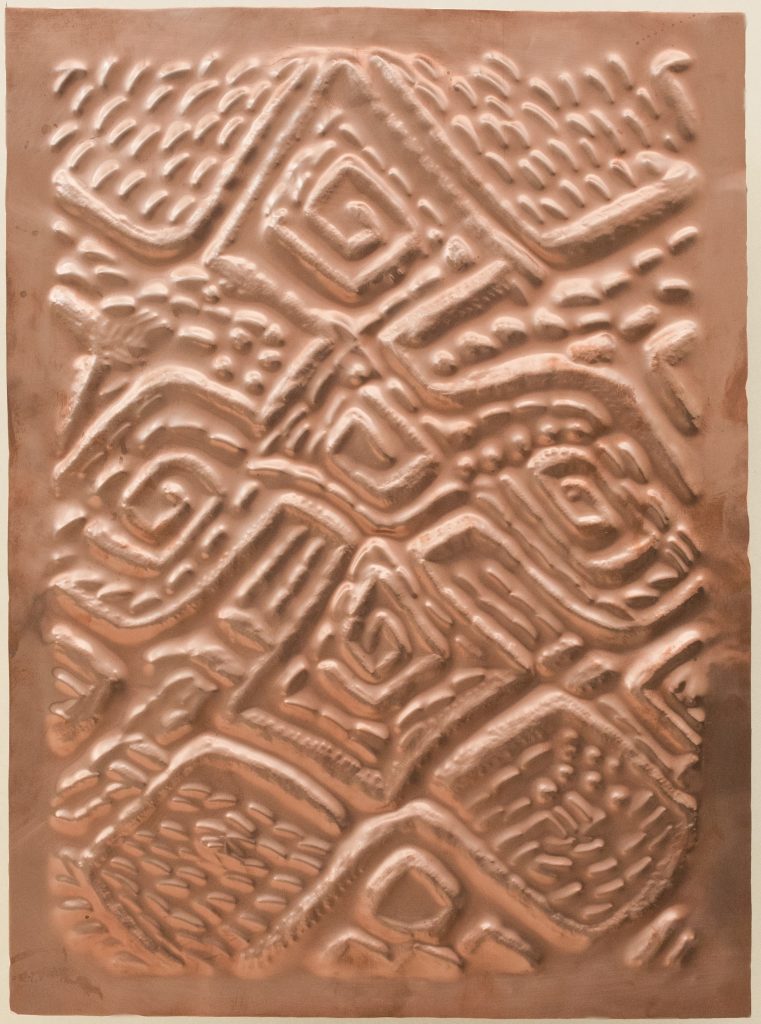

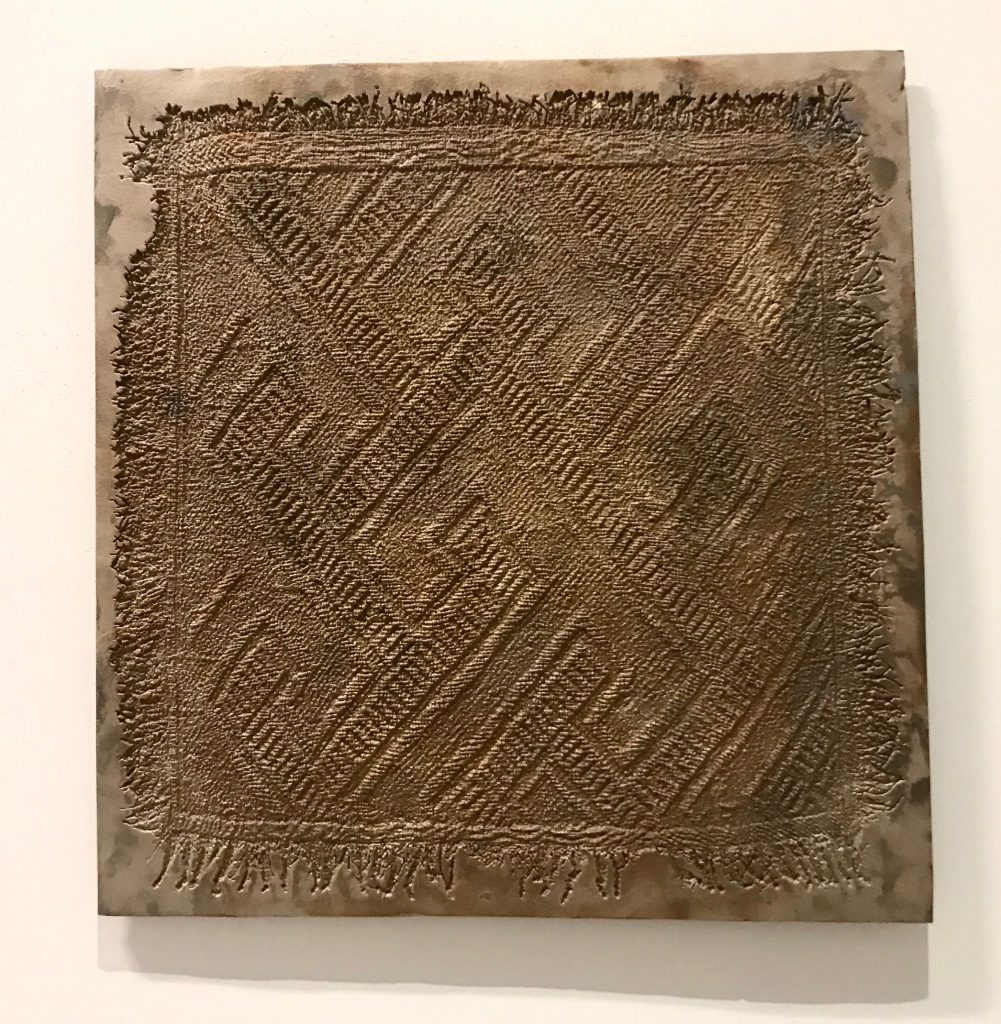

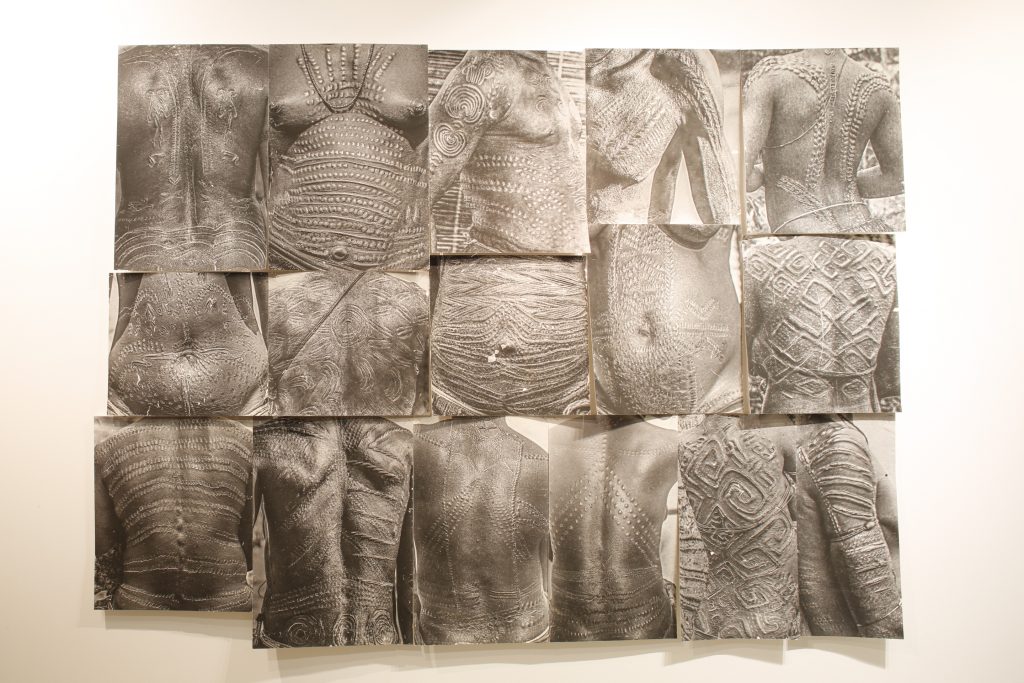

In 2015, Baloji began working with copper, creating a series of bas-reliefs and sculptures onto which dots, shapes, and lines create what first appears to be a sort of abstract patterning, but which in fact reflect patterns of body scarification from the late 19th and early 20th century, that reveal meaning about the identity and community of the people shown in these photographs. The roots of this project developed while researching archives at the Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, another country which Baloji calls home. The photographs he found in this archive were deeply troubling for the artist — highly clinical and voyeuristic, like studies of ‘the other in all their foreignness,’ yet they were links to his own past and community.

Seeking to create new meanings and re-frame them in a new light, he focused on the scarification seen on their bodies, an important trace that represented both their individuality and communities, thereby giving back, in a way, their identity and “erasing their objectification,” while creating an intimacy and connection between himself and his past. Cutting and cropping the images and then transferring them onto a new surface, the copper plate, further re-contextualized the photographic imagery, transforming it into an object.

For Baloji, it was interesting to look at these images and re-discover “traces of this cohesive social system, that is scarification,” which during colonization and, in particular, the impact Christianity, was slowly erased as people renounced their culture. “It was interesting for me to find these traces of the pre-colonial system, these links to history and say — look there was a whole cultural, social, aesthetic and meaningful system in place before… and working with this material as a way to re-direct the system, denouncing the political and economic impact that colonialism had in the Congo.”

The importance and influence of copper runs deep in Congolese society and for Baloji, it holds a symbolic meaning —both as a way to explore the geographic aspects of his homeland in terms of mining and resources, but also of geopolitics and time, and the reverberating consequences that the extraction of this mineral has had in the Congo.

Importantly, the copper used to create this body of work is not strictly from the Congo. As Baloji explained, “nearly all of the copper from Congo is extracted and exported, then fused with copper from other countries, such as Chile, and finally sold in massive quantities for large-scale industrial use.” For Baloji, this globalizing aspect of the copper is interesting—and he links it to his own identity in the world, as being from the Congo yet living in different countries, meeting people, learning, experiencing and creating his own presence within this space, this increasingly global citizen, who is part of many cultures and not just one.