Soft Design: A Short History of an Ordinary Object

For our S/S 2021 issue: TLmag35: Tactile/Textile/Texture, Francesca Picchi wrote a fantastic essay about the impact and importance of Italian sofa design post WWII – from innovative materials that allowed for more avant garde forms to the brilliant branding that made the world take notice.

The reputation of Italians regarding the typology of the sofa could depend on many factors, perhaps linked to a nature that is particularly inclined towards the pleasures of life according to the idea of otium handed down by the Latins, for whom detaching from the activities of public life is necessary to find deeper meaning to one’s actions. That may be one reason. However, it is also true that the sofa was subjected by Italian designers to a rigorous revision after the end of World War II: i.e., during the period of their country’s industrialisation and the conversion to civilian use of applications which had been dedicated until then to military purposes (such as foam rubber, which was used to protect ships’ tanks during air attacks, and which after the war became the material that permitted a rethinking of the way of sitting or, at any rate, the production of objects designed to accommodate the body by enveloping it in soft surfaces). These soft materials, such as foam rubber, Nastrocord (this ribbon of rubberised canvas emerged from research into tyres and was patented in 1948) or polyurethane, paved the way for simplified production of the rather recent typology of the sofa. This simplification made it possible, in fact, to overcome the complicated superposition of layers padded with horsehair or elastic springs – which required many hours of work – suddenly freeing the imagination.

It would therefore not be completely incorrect to say that the sofa, in its industrialised version, was invented, or rather reinvented, in Italy, and that this invention set off a series of chain reactions that drove this particular furniture typology to improve, as happens in all cases where a production chain is built around an object, capable of setting in motion many interests in order to create cost savings, even on a small scale. To explore the details of the invention that facilitated this industrialisation process, we need to proceed sequence, beginning with the discernment of Marco Zanuso, who was able to perceive an interesting perspective for development in the work of his friend and engineer Carlo Barassi: an employee of what was then the largest Italian tyre company (and thus a giant in the processing of rubber and its derivatives). Returning to civilian life after serving in the Navy during the war, Zanuso must have learned from his friend Barassi, with whom he shared a love of the mountains and skiing, during one of their many excursions to the mountains around Milan, about the invention that his engineer friend had spent so much time working on, and that he was on the point of patenting: Nastrocord, an elastic textile ribbon derivative of rubber processing. This composite material mixed textile and rubber and, thanks to its woven fibres, delivered excellent structural performance while enabling controlled shaping. By coupling the flexible structure created by interwoven strips of Nastrocord with the sensory and welcoming properties of rubber foam, Zanuso seized the opportunity to revolutionise the production system for furniture fabrics. The system invented by Zanuso was so simple that it generated a substantial market of imitations, setting in motion a new economy in Brianza (the agricultural region around Milan), with a particular vocation for the production of furniture.

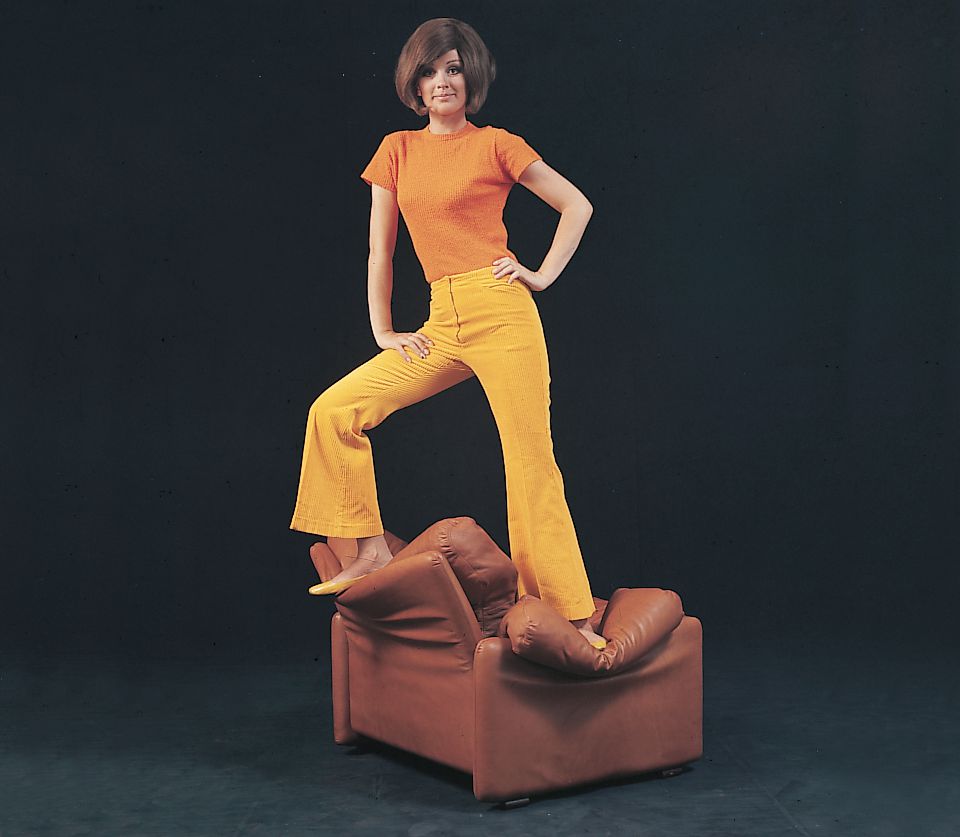

This context enables us to introduce the next phase, which marked a crucial turning point in the history of the modern sofa in Italy in terms of the innovation of processes regarding the introduction of new materials, because we must keep in mind that upholstered furniture is part of the history of plastic, its soft variant. Here as well, the sofa intersects with the history of the invention of new materials, because at a plastics trade fair in London in 1964, Piero Busnelli (a young and stalwart entrepreneur from Brianza), saw a machine that cold- moulded a soft cellular mass created by the mixture of two components, and (as he had been born in a small town whose economy revolved entirely around the pro- duction of wooden frames for the mass production of upholstered sofas) he immediately understood what such a soft mass – which chemical giant Bayer was about to put on the market, leaving it to inventive consumers to find new possible applications – could in fact be used for. When I had the opportunity to interview Piero Busnelli, I remember the excitement that still shone through his story when he spoke of the first time he sensed what could be done with a material like polyurethane foam. Together with Cesare Cassina, Busnelli founded one of the most famous brands in the furniture sector, B&B (which was initially called C&B, after these two eminent figures in the history of Italian furniture). Busnelli’s opportunity was to invent a way of moulding sofas in one piece like large polyurethane monoliths; and we can recognise that it is the company at the base of this famous Italian know-how related to the sofa, which quickly spread throughout the territory, becoming an integral part of the design culture. But beyond the purely technological aspects, we must also consider an aspect linked to the behaviour, or rather to the desires and inspirations, of a nation which, in a few short years, found itself an industrial power, leaving behind a rural history dating back hundreds of centuries. The new citizen-consumers wanted to immerse themselves in the symbols of well-being that would reassure them about the social position they had with some difficulty struggled for and attained; the same symbols that for decades had characterised the comfortable life of the ‘dominant’ class. Certainly, the sofa had never had a space in the peasant’s abode, and in fact this object was a candidate to become the heart of the most representative space in the house: the living room. Its dominant position was definitively established with the increasing presence of the television after 1954, the year when television broadcasting began in Italy.

This context helps us to better understand the revolutionary impact of the attitude of the Italian designers who, starting post-war, at exactly the time when every- thing needed to be rebuilt, began rethinking a common object like the sofa, by introducing a new perspective oriented on usage and not ownership, a concept that Cini Boeri, creator of the famous Serpentone sofa, summarised by proclaiming: “I did not intend it to be possessed, but rather used. And it was a bargain.” The Italian designers, driven by an intention to break the inflexible domestic divisions, understood that the sofa was the ideal target to raise questions regarding the concept of power that dictated the roles within the home.

In this sense, the emphasis on the use, or rather on the thousand-and-one possibilities of use, on the endless possibilities of combinations for creating and dismantling the domestic space, became key to promoting change. The Lombrico and Serpentone projects of Marco Zanuso and Cini Boeri, respectively, for C&B and Arflex between 1967 and 1971, could be seen in this way. Two products built around a repeatable module: a continuous sofa sold by the meter. Is it reasonable for us to read the transformation of a society through an object like the sofa? By studying how people sit? Around 1968, the sofa typology drew great attention from designers, who were questioning the roles and power of space in influencing behaviour. From this point of view, it seems quite natural that the protagonists of the radical groups identified the sofa as a piece of furniture suited to the reconsideration of middle-class life. As the sofa is involved in the way people gather, the young radicals thought to upset the rules by freeing people’s positions and gathering family members in a circle rather than in a row along a line that forced everyone to look in the same direction. From this point of view, it was certainly no coincidence that the most emblematic ‘objects’ of the best-known radical groups were sofas, such as the Superonda and the Safari, created by Archizoom and manufactured by Poltronova from 1966-1967. Or even the Sofo sofa of 1966, also by Poltronova, and Bazar, which appeared in Giovannetti’s catalogue in 1969, created by Superstudio, another essential group of this radical avant-garde.

The “headline” that accompanied Safari in advertisements reveals the power that the young radicals perceived objects to have in influencing people’s behaviour. “An imperial piece in the dreariness of your domestic walls. A piece that is finer than you. A very beautiful piece that you would not deserve. Clear your sitting room! Clear also your life!” The Safari project was therefore born in opposition to the production of upholstered armchairs and furniture, as ‘an emblematic representation of the well-being and opulence that Archizoom challenges with a systematic dedication’, writes Paolo Deganello, one of the founders of the Florentine group. Superstudio’s Bazaar should rather be understood as the expression of a ‘contemplative’ function which, alongside its practical function, is the objective of this type of “large, colourful, bulky”, object that is also “useful and full of surprises to live and play with”, that the members of Superstudio pursued. And then there is a purely technological reason. In terms of experimentation with new behaviours, when the radical groups discovered the shaping potential of polyurethane, they used it to give life to a series of powerful images built on the linguistic shift of the Pop matrix: a vast series of large lawns, cacti, baseball gloves, tents, Greek columns and Roman ruins translated on a giant scale and in flexible materials, have come to define the radical vocabulary. By acquiring a whole series of playful references, this new vocabulary of comfortable shapes spread a renewed idea of comfort based on the full fluency of the body’s positions. Certainly, polyurethane not only established a new vocabulary of shapes for furnishings, but it did the same for plastic materials, offering a soft counterpoint to the thin and rigid membranes of injection moulding, with its very complex and expensive moulds. Thus, requiring few technological resources, the flexible masses opened up a world of hospitable shapes with a hitherto unexplored freedom.

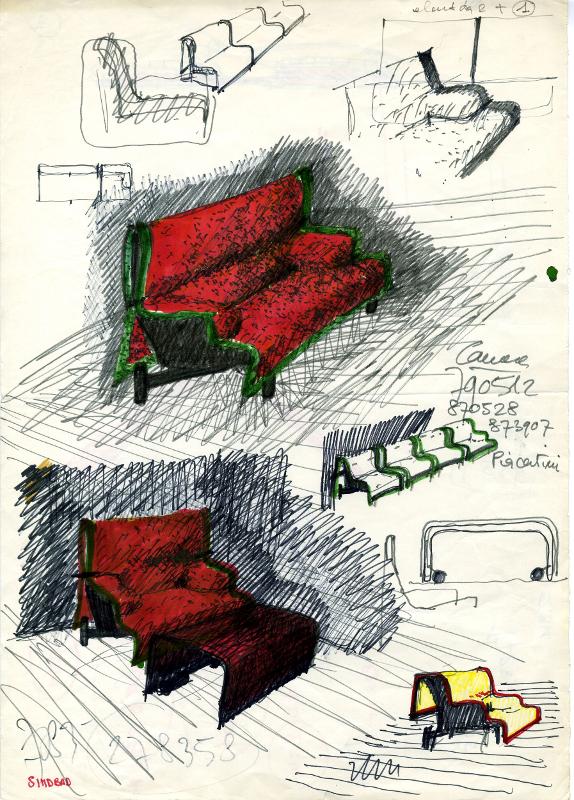

While, consequently, the radical groups profoundly modified the relationships with the domestic space, their influence was more omnipresent than could be imagined, because a large part of their research migrated into the house, domesticated by less ‘radical’ designers thanks to the concentration of experimentation in a single place, such as the Centro Ricerche: a space founded at the end of the 1960s by Cesare Cassina, specifically intended to be shared by Cassina and the company which subsequently took the name of B&B. In this site in the heart of Brianza, the research of actors motivated by a deep desire for change, such as Gaetano Pesce, or the aforementioned Archizoom and Superstudio, converged. The Centro was run by Francesco Binfarè, another inspired sofa designer, to whom we owe the most innovative models that have recently emerged on the Italian sofa scene, such as the Flap or On the Rocks models designed for Edra, which can be considered as a direct result of this research. While the Centro Ricerche represents a significant episode in the experimental dimension of Italian design, it can also be seen as the common denominator behind the production of some of the best-selling pieces of Italian design, which experienced enormous success and strongly impacted the national scene in the 1970s and1980s; from Mario Bellini’s Des Bambole, an enormous cushion which seemed not to have a rigid structure, instead appearing to be a large, soft mass ready to welcome the body (C&B, 1972), to Vico Magistretti’s Maralunga (Cassina, 1973), which was built around the concept of a mobile mechanism in the armrest that enabled the sofa to be transformed, in the best modern tradition of the furniture-machine. Both Bellini and Magistretti spent time at the Centro, translating the most extreme experiences emerging from the exaggerations of the young generation into a bourgeois language, promoting the metabolisation of their ideas within the domestic scenario, and supporting the bourgeois imagination.

But in the 1980s, with the linguistic liberty that was inaugurated by the postmodern poetical, a more thorough reinterpretation began, extending to the entire legacy of experimentation produced by modernity since the first decades of the 20th century, when the avant-garde movements pushed so far forward that they did not yet have the methods and techniques to translate their visions into reality. It is perhaps not so wrong to say that the sofa was also the focus object for the redemption of ‘bourgeois’ good taste, after years of linguistic exuberance had thrown the furniture world into turmoil. Antonio Citterio, for example, built his reputation on the sofa typology; this uncontested protagonist of modern Italian design, when a young architect, born and raised in Brianza, burst onto the scene in the mid-1980s with a project that was revolutionary in its own way: called Sity, this articulated system with a wide variety of configurations became probably the best-selling furniture product of the 1980s. The seating system, produced by B&B, was designed as a flexible and disconnected structure, comprised of some 20 distinct pieces. Compared to the idea of all-identical modular elements, Citterio designed each element as a finished piece that could be used alone or combined with others, creating so much freedom of combinations that “no Sity is the same as another Sity”, as the advertisements declared. In 1987, Citterio won his first Compasso d’Oro, which propelled him to the front of the Milan scene.

In parallel to this transcription work, for which Antonio Citterio is one of the most sophisticated and inventive interpreters, new players and new brands continued to break into this great collective work of exploring new soft forms. Certain events left traces, such as when Ron Arad burst on the scene in 1988 with a chair collection called ‘Spring’, which revolutionised the concept of elastic com- fort by exploiting the properties of harmonic elements in steel. It was at this precise moment that a company appeared, quickly becoming a main player in the typically Italian scene of the production of quality contemporary upholstered furniture: Moroso. It owed its development to the spirit of initiative of the daughter of the founders, who had until then focused on traditional sofas. When Patrizia Moroso enrolled in the new Faculty of Art, Music and Performing Arts which had just opened in Bologna under the aegis of Umberto Eco, she understood that she could put her experience to good use in the family factory, by experimenting with new languages.

In short, out of these episodes the role of the industrial substrate clearly emerges, comprising many small and medium-sized factories, dedicated to perfecting processes in the best modern industrial tradition, but with a difference, considering as well the eccentricity of the theme, namely a certain free, passionate manner that was not subject to the rational rules one would generally attribute to industrial design.

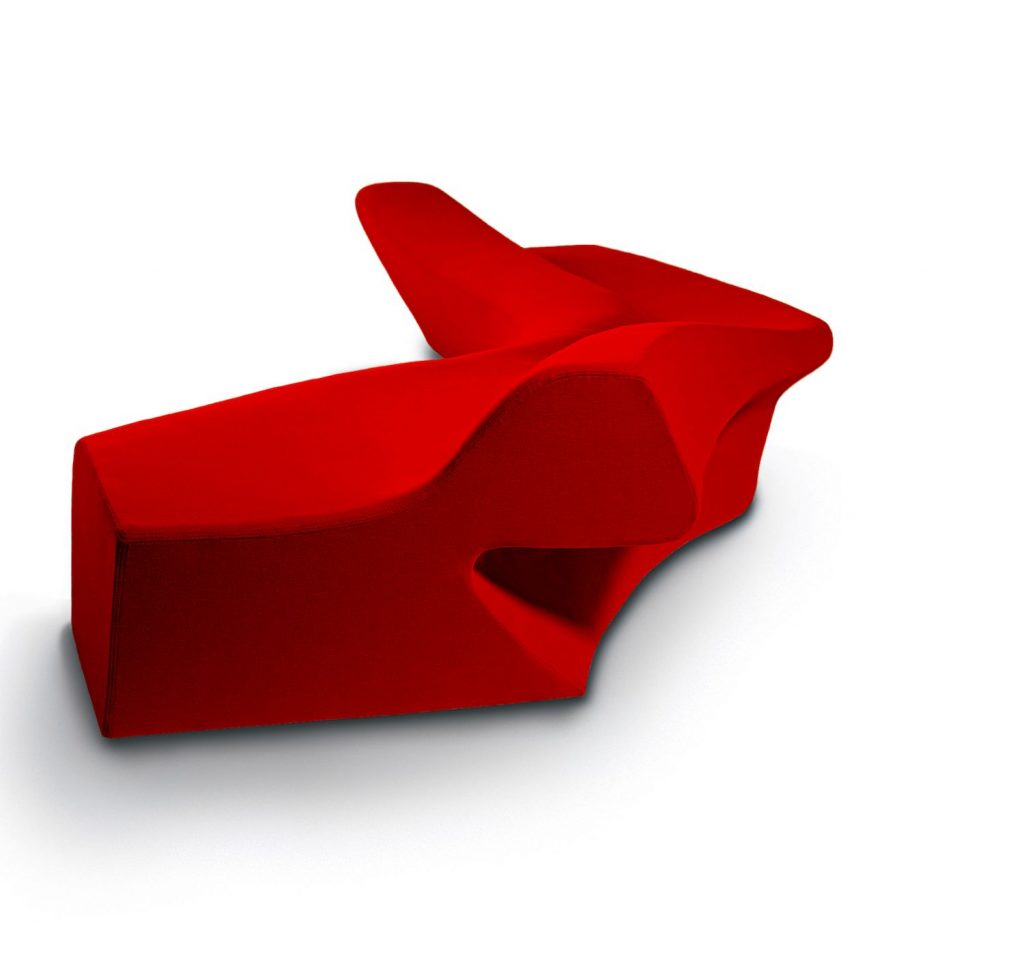

To underpin this ‘passionate’ tendency, I would like to conclude with an example impacted by the human and creative bond which united Zaha Hadid with William Sawaya and Paolo Moroni. This special bond of friendship prompted them, in 2000, to translate the visions of the Anglo-Iranian architect, inspired by the conformations produced by the natural erosion of moraines and glaciers, into the reality of a product: the Moraine sofa, a unique, 5-meter-long piece. The case of Zaha Hadid and Sawaya&Moroni reveals how this type of experimentation into the language of household objects is only possible thanks to the degree of refinement reached by an industrial structure that, with an artisanal mentality, preserves above all a willingness to experiment.

From these kinds of stories it also emerges, again in an unexpected way, that Italian designers and architects have been working on the sofa typology for a long time, with some players being particularly expert, from Piero Lissoni to Patricia Urquiola. Furthermore, we see that this competition for more and more sophisticated and inventive solutions has led the Italian industry to build up significant knowledge on production methods and invention of shapes, as well as upholstering solutions (for fabrics, textures and colours).

This type of latent story is so marginal and perhaps even ordinary that it caught the attention of Alessandro Mendini, who credited the sofa with the power to distinguish between two types of designers: those who can tackle the object, and those who seem incapable of handling its language. For this reason, Mendini also invented the neologism derived from the Italian word divano (which mean sofa) for those who “have in their blood the gift of knowing how to design contemporary Italian sofas.” Only the Divanista, according to Mendini “is capable of creating sofas as if they were myths, as a transgression of the living room concept, as an advanced proposition of life, as a morbid desire, like a mirage.” In short, to conclude: “One is born ‘Divanista’, one does not become it.”