Stefano Boeri: Pioneer of the Vertical Forest

Stefano Boeri believes in building high-density skyscrapers for trees inhabited by humans, which are aimed at improving quality of life by inviting nature into the city. If he had his way, our planet would be populated by entire sustainable, self-sufficient and smart forest cities.

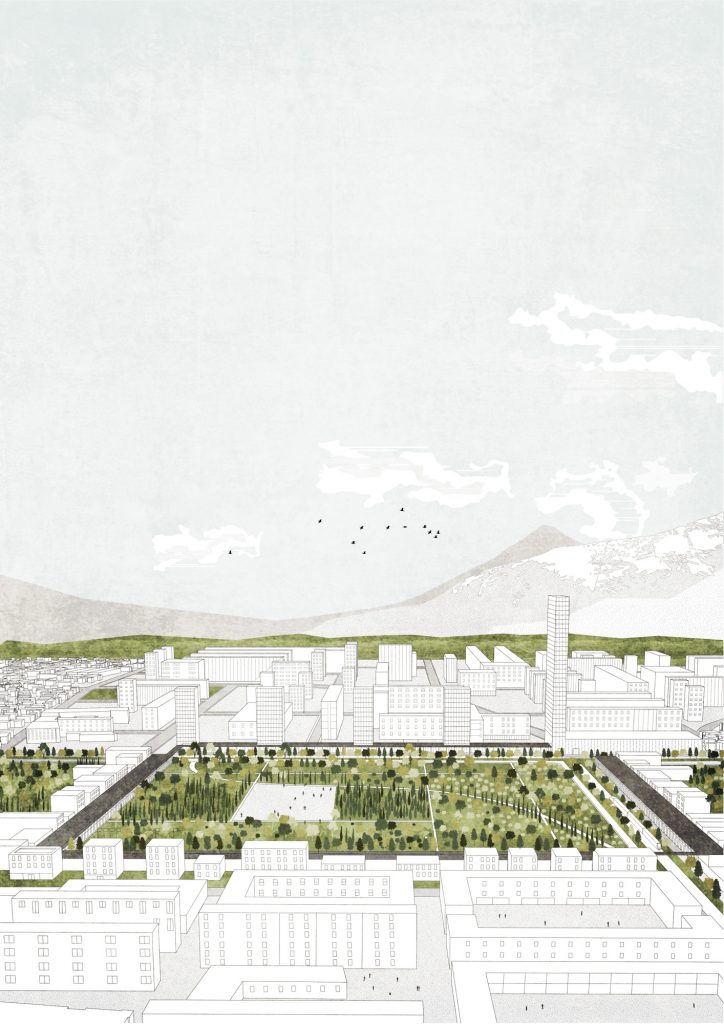

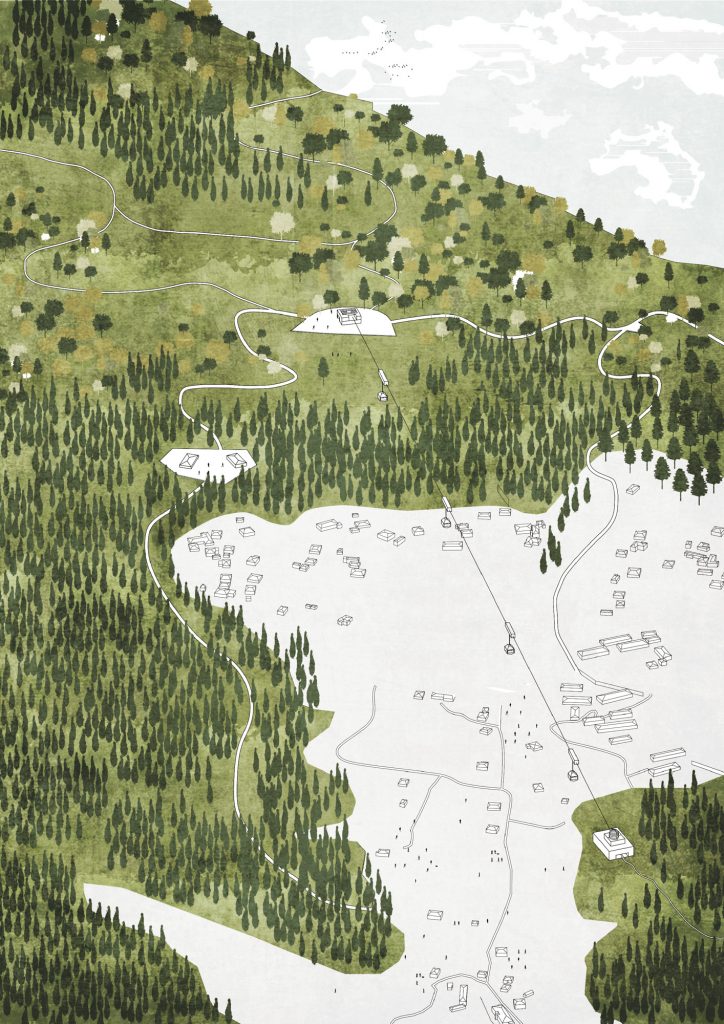

Stefano Boeri believes in building high-density skyscrapers for trees inhabited by humans, which are aimed at improving quality of life by inviting nature into the city. It’s not simply about integrating a green wall or roof garden, but growing plants and real trees – oak, beech, larch, olive, cherry and apple – on the balconies of high-rises. In 2014, the Italian architect, 63, completed his first Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) in Milan comprising two residential towers soaring 112 and 80 metres respectively, which became the first example of a sustainable development covered with 800 trees, 5,000 shrubs and 15,000 plants of 100 different species. The equivalent of three hectares of woodland and undergrowth is amassed in just 3,000 sqm of urban space, with all the environmental benefits that entails. This Milanese landmark has since become a model of metropolitan reforestation embracing the close cohabitation of architecture and nature for other cities worldwide to emulate. And if Boeri had his way, our planet would be populated by entire sustainable, self-sufficient and smart forest cities such as those he is constructing in Tirana, Cancun and Liuzhou.

TLmag: Tell me about your passion for trees.

Stefano Boeri (SB): I have always considered trees to be individuals. Each one has its own biography, expectations, trajectory and evolution. There is a novel, The Baron in the Trees, by Italian writer, Italo Calvino. It is the story of a young baron who at a certain moment decided to abandon his family and to spend the rest of his life working, studying, making love and meeting friends on the branches of trees in the woods. It was strong for me because it is set in Liguria, where my father was born. Another reference is Friedensreich Hundertwasser, an Austrian artist and architect who came to Milan for a manifesto on tree tenants. He said we have to consider trees as possible tenants like we are, and I remember this image of him walking in Via Manzoni and Piazza Duomo with a tree in his hands. Another important inspiration was all the work by Joseph Beuys, in particular 7,000 Oaks in 1982 at Documenta in Kassel, where he gathered 7,000 stones at the entrance of the exhibition and started to sell them in order to buy 7,000 oak trees. He then planted the trees all over the city, in the courtyards, streets and squares, which changed the city. This demonstration of the possible metamorphosis of an urban environment was symbolically strong for me.

TLmag: Why is the relationship between the city and nature such an important component of your architecture?

SB: Because I personally believe that we have to change in terms of how we deal with the concept of nature. Nature is not simply something that is outside, a kind of autonomous sphere of our lives. We have to start considering nature in a different way, as part of our way of life on the planet. We have entered into a new period of life in the future of the city where we cannot simply perimeter living nature inside the city by creating parks and gardens; we cannot simply put living nature outside. We have to experiment with a totally different proximity within the two spheres in many different declinations so that we articulate this relation in different parts of our urban environment.

TLmag: How did the idea for the first Vertical Forest in Milan come about?

SB: I started to work on a different way to rebalance the relation between the mineral environment and living nature many years ago, but I had the opportunity to develop this concept in 2007. I was in Dubai with my students, as I was teaching at Harvard University’s architecture department, and we were studying the urban explosion of Dubai. I was amazed by the wealth of this new city with hundreds of skyscrapers in the desert. I started to say instead of high-rise buildings covered in glass that reflects sunlight, why don’t we make them with a biological scheme, with a façade covered in leaves? Then I had the opportunity to transform this concept into a real project thanks to Jeremy Hines and the Italian CEO of Hines, Manfredi Catella, who wanted to try to transform one of the darkest and abandoned parts of the Milan centre. I answered with pleasure but please let me develop this idea of the Vertical Forest: a high-rise building with trees. At the beginning, they were very sceptical but they told me to answer a list of very serious technical questions: how can trees survive 100 metres high, how can trees be protected from extreme winds, how can tree maintenance be sustainable, how can irrigation be possible? I gathered a bunch of experts, we went back with the answers and they thought what we were doing was very serious and coherent, so they said, “Let’s start.”

TLmag: The idea isn’t to move into the countryside, but to bring nature inside people’s homes in the city?

SB: Yes, it’s totally another concept. We have to imagine a kind of double simultaneous movement: one is the movement of citizens in the direction of the forest because the forest needs our help, needs to be protected and maintained by us, and the second is the movement of trees in the direction of the city. If we want to tackle climate change, we now have many technologies like solar panels and geothermic tools to reduce the consumption of energy and use renewable energies. It’s important to invest in this kind of technology, but if we think how we can absorb the CO2 that we have already produced, we have only trees, plants and forests. That’s the basic reason for multiplying the number of trees inside our city because they absorb CO2 and transform it into oxygen, so I believe that’s an amazing and radical way to tackle climate change.

TLmag: In 2018, the Morandi Bridge collapse in Genoa caused the deaths of 43 people, and now you’re building Polcevera Park and Red Circle there. How can natural disasters become opportunities for the rebirth of a city?

SB: The idea is to bring together the maximum of technology in green forest management and the maximum of capacity in resources in start-ups in such a depressed, transfigured and destroyed environment. We’d love to show that it’s possible to rejuvenate this place if we invest our maximum intellectual and financial energies. In terms of urban forms, a pedestrian ring connects the different parts of the territory hit by the tragedy, which even before had been segmented into different parts, so this steel red ring is not simply a metaphor, but it’s one of the possible ways to connect different landscapes. The other ingredient is plants and trees, so the Dutch landscape designer, Petra Blaisse of Inside Outside, is going to work on a biodiverse park, several green settlements with an amazing amount of species of plants, shrubs and trees. We are also working with issues of mobility. It’s a very complicated project, not only about greening but about how we can regenerate such a complex and destroyed physical, natural and cultural environment.

Images courtesy of Stefano Boeri Architetti.