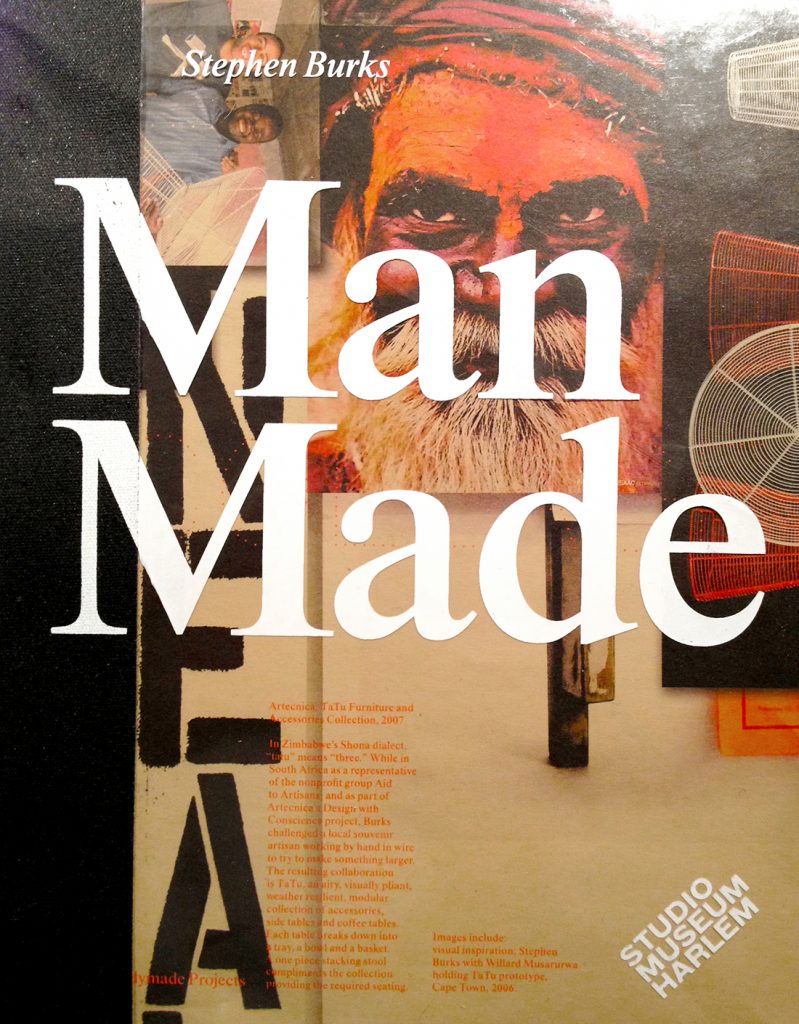

Stephen Burks Man Made

Stephen Burks on his relationship with Africa, working with African artisans, and the evolution of his practice.

Stephen Burks’s design practice — its formal name is Stephen Burks Man Made — often involves a connection between tribal traditions and a contemporary aesthetic, fusing together age-old artisanal craft techniques with the designer’s point of view. Growing up as an African American in Chicago, Burks always felt a connection to Africa, but it wasn’t until his first visit to the continent in 2005 that it had such a profound effect on Burks that he decided to start imbuing his work with African influences. In 2007 Burks worked with South African artisans to produce vessels from painted wire in the shape of Tatu tables for Artecnica and Senegalese basket weavers to make lamp shades and light fixtures from sweetgrass and vibrant recycled plastic.

TLmag: You were born and raised in Chicago. Do you know about your African roots, where your family is from?

Stephen Burks: Like most African-Americans that have not done their DNA testing, my African ancestry is unknown due to the ravages of slavery. Of course, we recognize it and oddly enough know more about our other ancestry including some Irish/Scottish and some Native-American.

TLmag: When and how did Africa start influencing your design practice?

SB: I grew up very much aware of my African roots and the beauty of its diverse cultures, but it wasn’t until 2005 when I visited the continent for the first time that I experienced it first hand and it truly influenced my practice. The first five or so years of my work were very contemporary and informed more from my Modernist education. It was when I was invited to work as a product development consultant in South Africa with the not-for-profit Aid To Artisans and actually saw the immediacy of making there in various craft traditions that I realized that design is a Western concept. Working directly with so many talented South African artisans with no education in design made me understand that there are other ways of looking at making as well as notions of design which are not of European origin that are just as valid and relevant.

TLmag: Recount your first trip to Africa and what did you take away from it?

SB: During that first trip to Cape Town in 2005, I worked with 12 different artisan groups for a couple of hours a day, on alternating days. It was like design boot camp because, for the first time, I was forced to understand the complete lifecycle of a product and how making that product greatly impacted the artisan’s life. In many ways, the risk was greatest for the artisan, the more innovative I attempted to be. Many of them were already losing money just taking the time to work with me, so I felt a great responsibility to share design concepts that could be immediately applied and have the greatest potential to positively impact their economic situation. It was a lot of pressure for a young designer, while at the same time, it was very exciting to see that what I designed mattered. For the first time in my life, I saw the direct consequences of sharing design thinking and strategies for product development that were the complete opposite of designing for the rich. I saw a new path for myself, which somehow related to my African identity and the need for design solutions for a population of makers that could have real economic consequences. I began formulating a plan to build a bridge from community-based artisan production in other places in the world to international distribution.

TLmag: Tell us about Man Made.

SB: Man Made is the philosophy or strategy that my studio attempts to live by. Our goal is to bring the hand back to industry, because we believe the closer the hand gets to the act of making the more potential there is for innovation. We are living through a time when more conscious consumers want more conscious products and certain manufacturers have begun to respond with more sustainable products. We attempt to align ourselves with clients and collaborators like this that allow us to participate in the design process is a much deeper way to find ways to bring new artisanal or craft-based solutions to contemporary design problems.