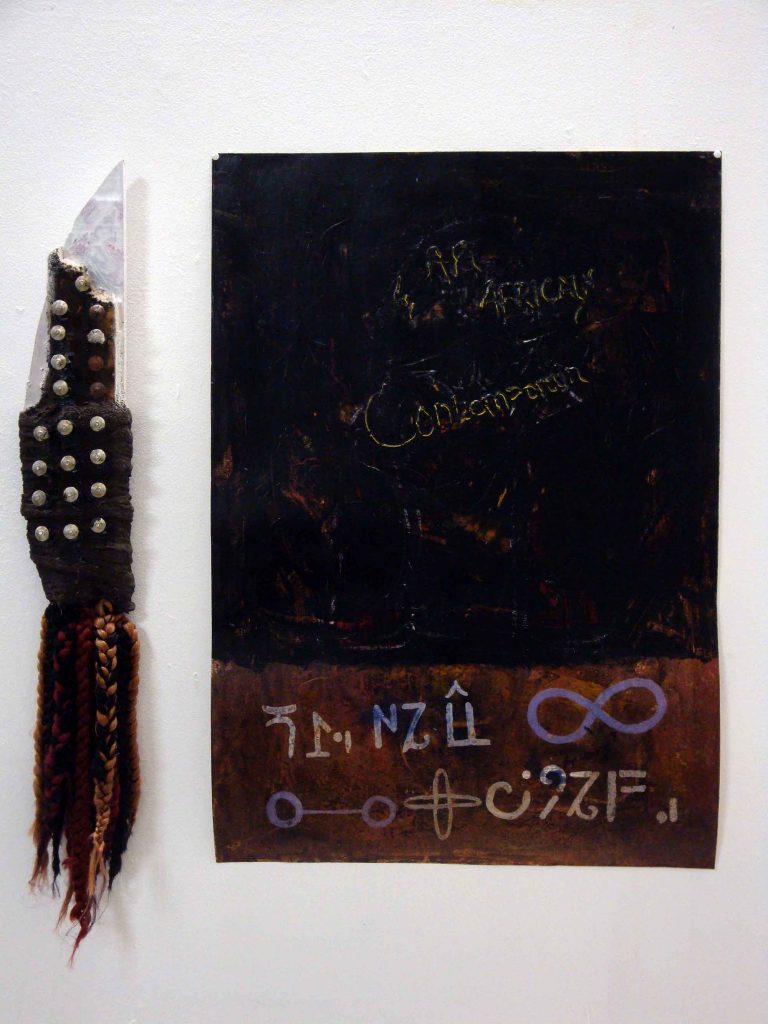

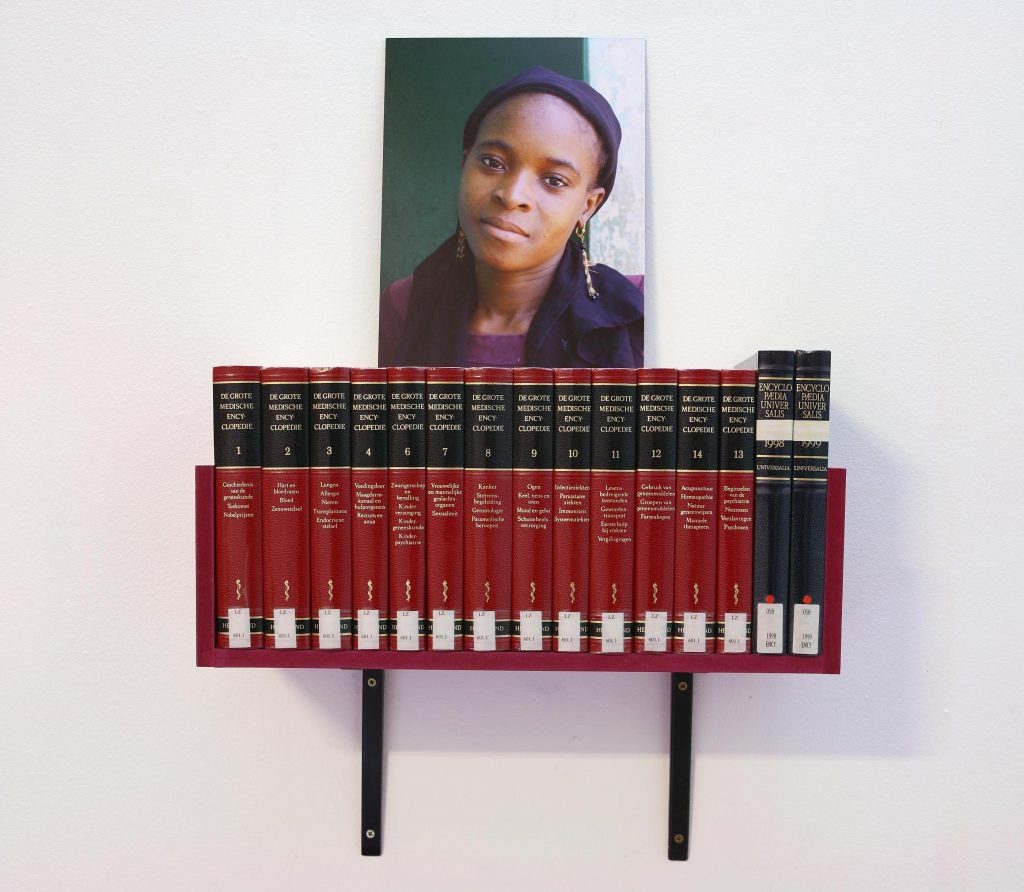

Walter de Weerdt: Collector, Curator and Gallerist

The owner of NOMADGALLERY talks about ten years with his gallery and his ongoing interest in contemporary African art.

Since the 1980s, Walter de Weerdt has been a central figure in the presenting contemporary African art in Europe as well as the United States. Starting as a passionate collector, he opened NOMADGALLERY, a semi-roving gallery in Brussels, in 2008, as a platform to support emerging artists, through exhibitions, and introducing their work to a new generation of collectors and curators, expanding for a time in Miami as well.

TLmagazine: How did you get started in this field? When did your passion for African art develop?

Walter de Weerdt: I started collecting tribal pieces in the late 1980s-early 1990s, mostly from lesser known tribes such as Moba, Tchamba, Ewe, and Lobi, and I was curious if I still could find these pieces in situ. While traveling extensively through West Africa, I came in contact with emerging artists in the capital cities and started collecting their work, including Moustapha Dimé, Viyé Diba, Sokey Edorh. In 1994 I wanted to go hear (Nelson) Mandela’s maiden speech in the “new” South Africa and while I was there I had time to visit artist studios and galleries in Johannesburg and Cape Town. This first trip was a discovery and as I continued to go back in following years, I found inspiration in artists like Kay Hassan, William Kentridge, Norman Catherine, Sam Nhlengethwa, and Willie Bester. My network was expanding and the collection started to grow rapidly. Friends and collector’s pushed me to open a gallery space in Brussels dedicated to contemporary art from Africa.

Nomad opened in 2008 – ten years ago this year. Can you tell us about how the gallery has evolved and changed over the last decade?

NOMADGALLERY has been in three different locations in downtown Brussels – this was part of the nomadic concept of the gallery – and it started bringing quite a lot of new artists, many exhibiting for the first time in Brussels. Art Brussels was the next step, we were the only gallery showcasing contemporary art from Africa and from the Diaspora. Shortly after NOMADGALLERY started exhibiting at art fairs in the United States and Switzerland, and then we decided to open a central point in Miami to develop business in the United States. Most recently the gallery relocated in Brussels to be connected to its origins and we opened a private space in the Place du Châtelain neighbourhood. NOMAD is focusing on art advising and coaching artists with their careers.

Though Nomad is dedicated to emerging artists – many of the artists you began working with 10 years ago have developed important, international careers, thanks in part to your support of them early on. Is there a dialogue among the gallery artists between some of older generation and younger generation?

Of course I always wanted artists from any generation and location to be in dialogue. Most of the artists with whom NOMAD has been working are now a part of a vast network and artists meet at art residences, museum shows, art fairs, exhibitions. I really think they support each other and appreciate each others artistic careers. If not, I am always there to make it happen.

Do you continue to develop curatorial projects outside of the gallery?

I have been involved in a couple of exhibition projects with a focus on Africa, not only in Europe but also in Africa, including Senegal, Mali and South Africa. But again, my focus is now more into advising new and existing collectors in contemporary art from Africa and the Diaspora.

How do you see the rise of art fairs such as 1:54 adding to the growing interest in contemporary African art?

All artists need a larger and more international platform to develop visibility and there is a motivation to be shown at Frieze, the Armory or Art Basel. Of course only a few get there and so art fairs like 1:54, and more recent AKAA are a good start to see art from Africa and from the Diaspora. I personally regret how art, including African art, is more of a business model now and not a pure personal discovery.

What are you looking forward to seeing at the Dakar Biennial? What excites you most right now about this event?

I have been at the Dak’Art Biennale since 2006 and present at most of the editions. This 2018 Biennale is probably the largest ever in Africa, but don’t get me wrong, after the opening week there is not much happening like at other Biennales. My visits are more to connect with artists and art professionals and hopefully also to discover new talent.