Zumthor: Architecture for the Present

Sound is ephemeral. It reminds the listener that it is fleeting as it fades away at a rate distinct from those of the other senses. Echoes, however soft or lasting they are, are seemingly literary reminders of that which just occurred. The echo places you in the proximity of the now, and that is what we see in the work of Peter Zumthor.

There is this video on YouTube of the cellist Isang Enders playing Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 inside Zumthor’s Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle in Wachendorf, Germany. The suite’s melody is instantly recognizable. It is one of those works in the cannon of classical music that will have a staying presence as long as time remains immortal. However, the specific performance that Enders delivers is different. It is not “different” in the sense of how he approaches the technically demanding octave jumps or the phrasing of each stanza, but rather in the ephemerality of its delivery. While the notes on the music’s score will more or less stay the same for generations to come, the space in which it is presented is constantly in flux. And as I watch this video again and again, I cannot help but focus on the acoustics of this small, concrete chapel in the middle of a farmer’s field. The warm sound of Enders’s cello are absorbed by the chamfered and crenelated walls; the notes do not linger in the air. They are of a specific moment, before escaping into the ether beyond and replaced by another set of phrases, which soon enough give way to the same expanse beyond. It is something as enigmatic as these fleeting notes that I believe is demonstrative of Zumthor’s architecture that underscores the “being” in and of the present moment. It is this sense of being that transcends both temporal and physical manifestations of the word. Those present in Zumthor’s spaces develop an acute sense of not only their own presence in relation to the physicality of the architecture, but an understanding of their temporal location. This multivalent approach to the concept of “being” allows for an architecture that is mutable in not only engaging with a multitude of contexts, but also a diversity of people that interact with the space.

The Aura of Wisdom

In the era of the “Starchitect,” Peter Zumthor is a bit of a peculiar figure in that he shuns the media’s attention. In many newspaper articles, authors often note how Zumthor is an elusive character. He is hard to pin down for interviews, leaving journalists and academics paging through his writings for the answers to their questions. When he travels, unlike his fellow Pritzker Prize peers, he keeps a strategically low profile, as a degree of anonymity affords him the possibility of becoming an observer of a given environment. It is not as though he shuns attention – he has effectively cultivated a brand about his name and ideas – but his notable absence from the spectacle of the media is defining part of his aura. And it might be the word aura that best defines him, as it is also what synthesizes his work. His atelier, in the small town of Haldenstein in the Graubünden canton of Switzerland, is removed from the distractions of city life. Like a modern day version of Henry David Thoreau and other transcendentalist authors of the 19th Century, this isolation from the hubbub of the city allows for a practice that engenders self-reflection.

Trained in the design of furniture and having cut his teeth in working in historic preservation efforts, Zumthor’s path to becoming an architect bucks the model typically followed by his colleagues. But his desire to work on a scale that defines space, rather than merely creating one of many delineations that mollify an environment, is influenced by a diversity of factors. From poetry to music, conversations to smells, these elements meld together to form Zumthor’s architecture. But how they come together is in the form of experience, which becomes illustrative of his ideas. Zumthor has noted in his published works such as Thinking Architecture that there is an aspiration to tease out the past by material means. He stokes the axiom connections in mind – those little understood synapses that mysteriously define our being – as a means of creating an architecture that goes beyond dimensioned space and into the space of our animus.

Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle as Manifesto

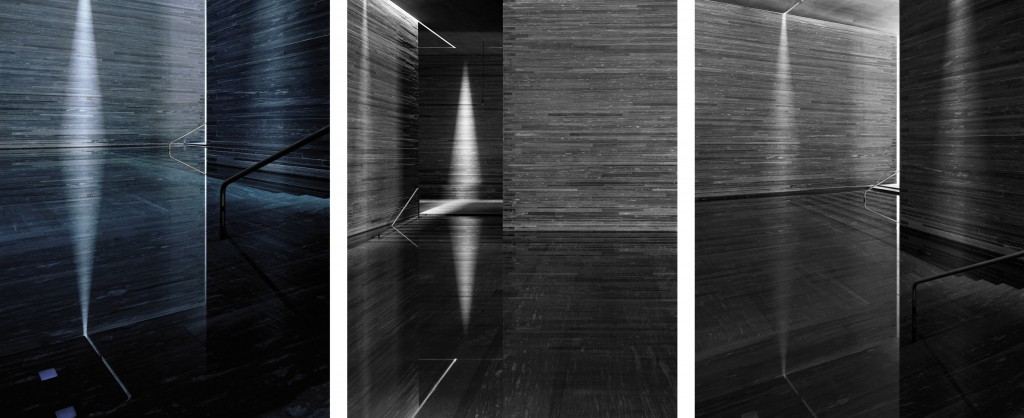

The concrete edifice of the chapel breaks the flatness of the plane. Interrupting the swaying grasses that surround it, the formal characteristics of the chapel are a break from the normative chapel typology. Gone are the peaked roof and the wooden clapboard construction. The roof of yore is jettisoned in favour of an oculus that brings the outside elements into the heart of the chapel, and the presence of wood cladding the exterior is limited to horizontal striations of the formwork that line the exterior are the remnants of its construction. They are an index of the labour put forth by the farmers, a marker of their devotion to the patron saint, Brother Klaus. This envelope, as in other examples of Zumthor’s work, is distanced from its interior, both visually and conceptually. The poché space in between is a zone of transition, punctured only by a triangular door and a celestial array of round, windows no larger than a €2 coin. The walls, meters thick in some places, create a clear delineation between temporal and spiritual realms. The interior space stands in contrast to its envelope, as the texturally rich walls, created by burning away a rough, timber formwork, keeps one eye scanning the surface.

Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle is a structure that stirs emotions; it evokes a sense of spirituality that is wont to escape words, but still reverberates in one’s bones in fleeting ways. That chapel is an exploration of how something so simple can work on a myriad of levels. This excitation is central in the construction of the awareness of being. In many ways, the awareness of the self is paramount in the act of prayer. To know oneself in a space that helps construct the framework that underscores the idea of consciousness as protagonist is where Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle succeeds. Even when those in the space are not Catholic, the spirituality of the space is able to resonate, much like the notes of Bach’s cello suite. The limited echo in the structure is legible as underscoring that there is only a “now.” There is not a past or future in this space, just a present. It is a deft architectural feat to design a space that speaks literally to the immediate moment.

Architecture, as a totality, is wont to speak to a specific moment in time, but it often lives in the past. Aesthetics are easy to blame here as a public finds it easy to locate form within a historical spectrum. However, to create this timelessness in a structure loaded with the weight of iconography is remarkable. Looking at the solitude and performativity of Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle, we see a space that is able to work on many levels simultaneously. Something so simple and understated can do so much.