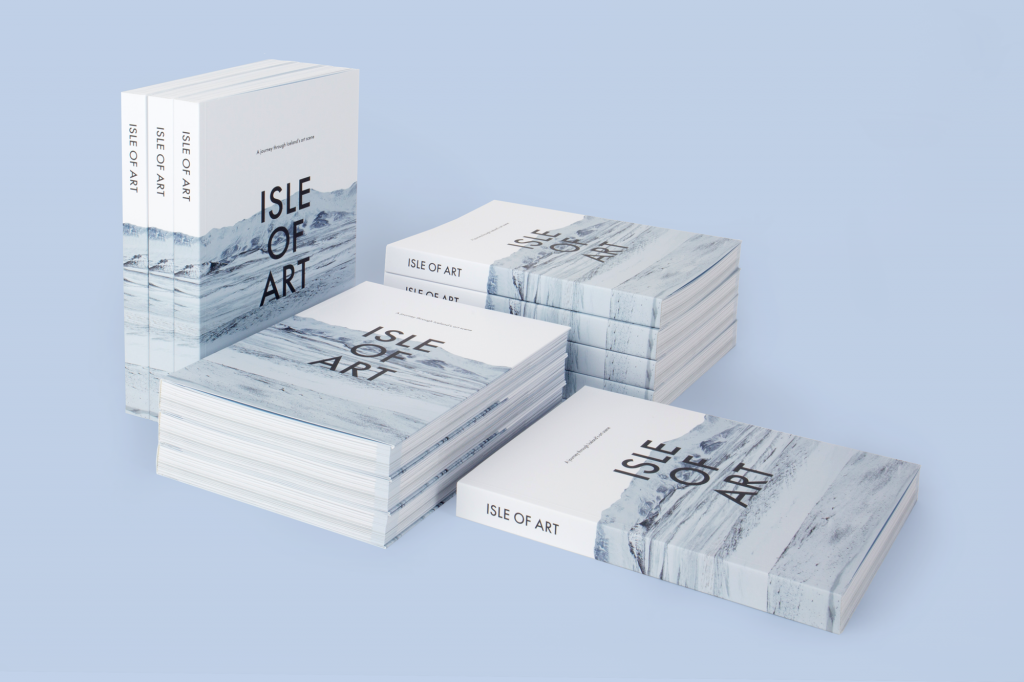

Sarah Schug: Isle of Art

Sarah Schug dove into the exhilarating art scene of Iceland together with photographer Pauline Mikó, to create the book Isle of Art. It reads as a journey in which the Iceland’s artistic landscape is introduced in 256 pages, meeting artists, curators, collectors, museums, and many more. TLmag caught up with Sarah Shug to learn more about this adventure.

Sarah Schug dove into the exhilarating art scene of Iceland together with photographer Pauline Mikó, to create the book Isle of Art. It reads as a journey in which Iceland’s artistic landscape is introduced in 256 pages, meeting artists, curators, collectors, museums, and many more. TLmag caught up with Sarah Schug to learn more about this adventure.

TLmag: Could you take us through your first, initial spark that inspired you to start on your book Isle of Art?

Sarah Schug (SS): The first time I came in contact with Iceland was at the age of 7 when the TV series Nonni & Manni was broadcasted in Germany, the story of two brothers in 19th century Iceland. I fell in love with the horses, turf houses and waterfalls. Since then I wanted to see Iceland, and I did so for the first time in 2009. I fell in love with it again and returned several times. Of course in the meantime, I already knew Iceland’s musical output (Sigur Ros, Björk, Múm, etc.) but visual art was a bit of a blind spot. It’s very underreported compared to the music scene, although it’s no less vibrant and innovative.

I’ve been working as an art and culture journalist and Icelandic artists started popping up in exhibitions in Belgium, I wanted to find out more about the subject. I actually searched for books about it, and couldn’t find much, except monographs. I really felt like there was a gap to be filled. When I told my friend Pauline Mikó (Belgian-Hungarian photographer) about the idea and she proposed to do the photos, I decided to just go for it.

TLmag: How would you describe the book’s narrative, and how did you curate the artists that are featured in the book?

SS: The book is completely focused on contemporary art: artists, gallerists, curators, framers, collectors. It is divided into sections corresponding to geographical regions (Reykjavík, Westfjords, etc.), with each section featuring the artists, museums, galleries and outdoor art pieces in the respective region. Accordingly, it reads a bit like taking a journey around the island. As to choosing the content: it all started with a lot of reading and desk research. Then, I went to live in Reykjavík for two months. On the day of my arrival, I directly went to an opening at the i8 gallery. During these two months, I attended lots of openings and exhibitions, visited art spaces and galleries, and talked with many people from the Icelandic art world: I got to know the scene from the inside. The lack of existing literature on the subject meant that word of mouth was the principal source of information.

In the end, you quickly get a grasp for what’s important, which names come up again and again, and so on. No matter how successful, everyone seemed within reach – perhaps unsurprising in a country where it’s reportedly not uncommon to find yourself sitting in a hot tub at the local pool next to the president. The accessibility of this small, tight-knit community -unheard of in art hotspots like Paris or London- facilitated the creation of Isle of art. Regarding the selection, it was very important to me to paint a full picture of the art scene as a whole by bringing together a rich canon of different voices and perspectives from inside the Icelandic art community. This means that the book features newbies and old-timers, Icelanders and foreigners, young and old artists, students and stars. The idea wasn’t to show “the best” artists (whatever that might mean) but a kind of mosaic, if you will.

By reading the texts and interviews, questions like the following are being answered: What factors shaped Icelandic art? Is there a common denominator? How has the scene changed over the last decades? What does it mean to live, work and create as an artist on a remote island in the North Atlantic? How does such a tiny scene function? What are the highs and lows of living in a small art community? Why would a Paris-based artist decide to run an art space in a remote fishing village here? Why exactly is the scene so vibrant? And how does one deal with the lack of an art market?

TLmag: Even though you were previously well acquainted with the Icelandic art scene, I’m wondering whether there are any new elements or perspectives you’ve learned on the Icelandic scene?

SS: Definitely. First of all, it’s important to acknowledge that there is no such thing as “Icelandic art”. It’s contemporary art just like everywhere else: artists are making everything from paintings and sculptures to performance and video art and photography. But there are a few things I found striking when it comes to Icelandic artists: there seems to be a certain carelessness, fearlessness and confidence resulting in this very Icelandic “just do it” spirit. I think Börkur from i8 Gallery, the country’s oldest commercial gallery, put it quite well. He said: “Those who have some talent and work hard: nothing is stopping them. There is nothing in the system to hammer them down. If they’re good they’ll just continue. Everyone else will fall off the wagon, but much later than in other places. When I was an art student in London, half the people quit right after we finished. On graduation day, half of them gave up.”

There’s also a strong spirit of creative freedom, playfulness, collaboration, and experimentation. This might be rooted in the fact that Iceland is still somehow at the sidelines of the art market. There are maybe 5 serious collectors. Many artists talked about how no one really even thinks about selling, and they are shocked when going abroad how artists are very occupied with this thought already during their studies and run one-man-businesses. It’s a very different mindset when it comes to making art. From the outside, this outsider position might be seen as a burden, but talking to the artists it widely seems to be considered as a boon.

TLmag: In what ways can you imagine the Icelandic art scene growing? What are the chancesand opportunities for the scene?

SS: The scene is becoming more professional and more international. Coincidentally, I did my on-site research during a historic moment for Iceland’s art scene; a period the art community has dubbed “game-changing” for art in the country: the opening of Reykjavík’s Marshall House. This new flagship arts complex and award-winning architectural gem in a former fish factory brings together the country’s most significant artist-run and commercial galleries under one roof. It’s a stamp of approval and vote of confidence for the future of an already thriving art scene that has the potential to be a new destination on the international art map. It’s also the material manifestation of a widely-shared feeling: Iceland’s art scene is growing up.

Globalization, digitalization, and the explosion of international travel have caused the island’s once rather closed-off art scene to become bigger, more professional, and more diverse. It is common now for local artists to venture abroad to study, work and exhibit, while foreigners arrive on the island in no small number to create and show their work. Reykjavík’s art schools’ academic offer didn’t go beyond Bachelor’s level until 2012, and it became fashionable for local artists to pursue Master’s degrees in another country. It can now be considered part of the international art world by any objective measure. The country has all the ingredients necessary for a vibrant scene, namely commercial galleries, museums, art schools and a multitude of independent art spaces. Especially the number of commercial galleries has been growing, a significant indication for the increasing maturity of the scene. It’s, of course, a good thing, but personally I share the feeling of many Icelanders who hope that despite all that, the scene will be able to keep its unique playfulness and freedom. Icelandic curator Markús Þór Andrésson encapsulated it perfectly in his interview: “There is this weird struggle between maintaining your identity as the art scene that has no history, no money, no collectors, and no galleries, which was very much the case for the second half of the 20th century, and want to be one of the big boys. We got what we wished for, now what? There is a sense of loss as well. We lost this innocence of being able to claim “we have no history so we can do whatever,” something that had been the artists’ mantra here for a long time.”

Cover image: Lilja Draumland Photography.