Tal R Does “Academia”

The extensive work of the Danish artist is being displayed in a mid-career retrospective, the Academy of Tal R, at the Museum Boijmans van Beunigen in Rotterdam

In Copenhagen, Tal R’s studio is having a tech issue: the artist is producing work so rapidly that they’ve run out of gigabytes to store the documenting images. “He’s painting faster than we can exhibit,” jokes Sjarel Ex, the director of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. The Rotterdam institution is hosting the Academy of Tal R, a mid-career retrospective initially displayed at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark.

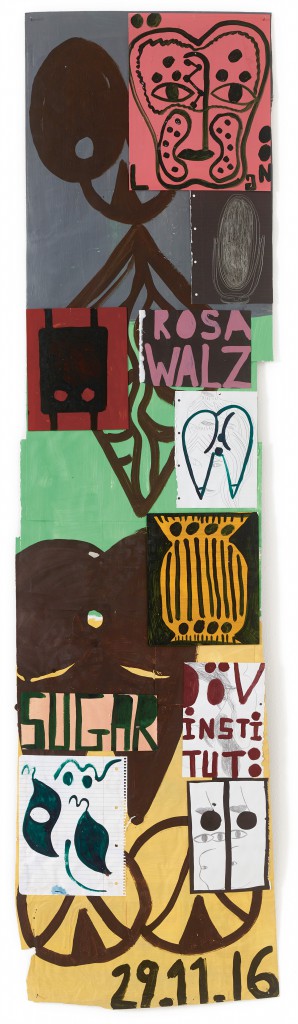

Judging by his quiet yet joyful energy even at an early hour, the day before the public unveiling of the Academy, R has all the markings of being a morning person. Judging by the sheer amount of work on display, he has all the markings of also being a midday, afternoon, evening and night person. There are paintings, more than 40 sculptures, several weaved pieces, large-format collages and more than 50 —yes, 50— different books on his projects. And then there’s the Deaf Institute, a labyrinthian walkthrough installation made of 99 poster-like pieces.

He can’t stop: he has finally found his groove. After years of fighting with the canvas, with techniques, with himself, he has come upon a process that works. “There was always a struggle, but after a while I started enjoying the fact that it’s always a struggle, and the struggle became like a game,” he explains. In a visit to the exhibition, we discussed his hyperproductivity, his hoarding and the painting technique that came at just the right time in his life.

TLmag: Some of the drawings in the Deaf Institute reminded me, of all things, of Caribbean aboriginal art. That’s the last thing I’d expect to see in the work of a Dane.

Tal R: Applied art, carpets, rugs: if you look at that for a long time, you’ll find out that everything arises out of the same type of ornament. And that means that, in every culture, at a certain level, you will find this sort of pattern. One circle and two spots is a face —many of these things, you could say, are typical. These patterns probably also exist in Siberia, because it is the basis of geometry. Before geometry became mathematics, it was everything you could do in the sand.

Carpets don’t care about borders. These patterns move around. There are not that many possibilities. There are many variations of the same possibilities. If you take something like zig zag, you could do it like this, like that, and all the other variations of this. Drawing goes one way and language another, and there’s this point where they touch: that’s where drawing almost becomes words. In ancient cultures there were no written languages, only drawings. That’s the weird place where they just touch.

TLmag: So, the oral history and visual history come together?

TR: Yes. And the reason why this is called the Deaf Institute, although it’s not proper English, it is because it’s for the eyes. You see and experience all this information.

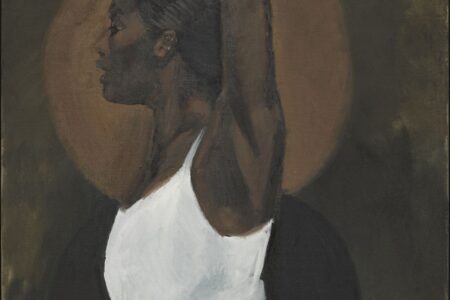

TLmag: Moving to another section of the exhibition, let’s talk about the paintings in the large-format section. Why did you decide to use a difficult material like rabbit-skin glue on such big surfaces?

TR: It’s not so easy to work this way. You take the rabbit skin, you put it in water overnight and you work with it when it’s under 40 degrees. The difficult thing is that it’s a bit like a fresco: you can’t re-edit. You have to move forward, and it if doesn’t work, you have to throw it out —it’s not like oil panting, where you can keep going back and forth. If you don’t use this technique in the proper way, you have to start all over.

The colours here are on the canvas, but look like they’re above it, in the air. I started this eight, nine years ago. This is the only technique where you can have the colours pure like that; they look like pastel. I needed them to look like they were in the air, not on the canvas. Oil painting is like ketchup… this is more fragile.

TLmag: How did you start working with it?

TR: I was a professor for many years in [the Kunstakademie] Düsseldorf. There were other colleagues working with the technique: usually artists use this in the beginning, and then put oil on top, but I was interested in this alone. I liked the texture of it. But I wouldn’t have had the patience for it 20 years ago. It would have driven me crazy. The moment you put it on the canvas, it sucks into the canvas. You have to be quite calm and quite clear about your ideas.

TLmag: What were you like 20 years ago?

TR: I had one foot in where I came from, where painting was for me always about having an idea. When it didn’t work, I would just destroy it, and in the process of doing that, something interesting would come out. I was almost dancing on the canvas out of anger when it didn’t work. Around 2007 I got clearer about narratives. I became interested in narratives that I could explain to you over the phone —something almost boring and simple, like, for instance, “the moon reflecting in water” or “three women on a veranda” or “boy with pijamas.” Almost boring, but the moment you see the painting, the whole experience is different. For this, I needed a different technique. I needed to make the restriction of not being able to edit. You can only march forward.

TLmag: But other subjects are very, very local for you. This is the Louise bridge in Nørrebro, for example.

TR: Some years ago I started being interested in something: Why can’t painting be what you see while walking down the street? Or the people you are around when you look out the window in the morning. Art history set out with that kind of approach in general terms, only amateurs would work like that, but now everyone with an iPhone is working like that. The necessity for showing other people what they saw in that specific moment is still so deep in us. This is a man I saw sitting there. This is the façade of a sex shop in Soho in London. This is also Louise bridge, a guy who was sitting there drinking milk —which is a weird thing for an adult. I did so many versions of this painting, and this is the most messed up one. It’s called Little Milk.

This is somebody I saw taking a shower. The privacy of what you saw is always a dilemma. If you need to show an image like this to there people if comes from the private but it’s not private anymore. That’s always a dilemma as an artist.

Look at this one: it sounds like a stupid pop song. “There is a shop selling empty frames.” It’s almost a cliché for philosophy. After I did this, I was interested in the idea of façades. There is the pavement, you look to the window and if you find it attractive, you go in. And then you notice the backroom and you can only imagine what’s in there. That’s also the basis of painting. It’s an interesting thing that we think that artists know what’s in there. I paint because I don’t know what’s in the backroom.

TLmag: Did you face that with the sex-shop paintings?

TR: I paint them because I don’t know what’s inside. I’m only interested in their façades. Painting is flat, and so is a sex shop. You never see what’s inside.

TLmag: Some of these paintings made me laugh on the inside.

TR: It’s a very serious game when I do that… but very playful, and I enjoy it a lot. You know where you’re going but you don’t know how to get there. It started as a disaster when I was younger, and that’s why I destroyed so much. There was always a struggle, but after a while I started enjoying the fact that it’s always a struggle, and the struggle became like a game. I know I’m in the right direction when I’m on thin ice.

TLmag: According to the tech person in your studio, you seem to be on thin ice far too often.

TR: Yeah, I keep a lot of stuff. Also, the sculptures: whenever I do a sculpture, I like to do a family of them. If I find a certain topic —for instance, I did something called The Egyptian Boy—, you need to follow it until it crystallises, and that means there’s a lot of work. I do it myself, nothing is painted by any assistants.

TLmag: And yet I’m surprised by the amount of work labeled “2016” and “2017” in here. It’s a lot.

TR: I think the reason I’m good at playing with the work is that I’m very structured. The moment you start playing, there’s a structure about it. That doesn’t mean you know what’s going to happen, but you keep that possibility. I don’t know how to explain it. But I also get dizzy when I see how much I’ve done. But I don’t look back. When this show was in Louisiana, I went there for the opening and never went back to look at what I had one.

TLmag: So it’s true that once you finish a series, there’s a visual mark to the last piece, and it’s over.

TR: I’m not nostalgic with my work. I’m more curious with the things that I haven’t done. That might be brutal, but in the end, artists will always try to tell you that they choose strategies, but they don’t: it’s just the way you are. What’s interesting with art is that some of the qualities you have as a person, that would be quite bad in society if you had a normal job, are actually advantages as an artist. That’s also the reason why some people decide to be artists: they know they’ll fail in other places. Mistakes are what make art grand.

Academy of Tal R is on display until January 21, 2018