Building Blocks

For the A/W 2020 TLmag34 – Precious: A Geology of Being, Tracy Lynn Chemaly reported on four innovative architectural firms using traditional clay bricks in pioneering architectural projects. Economical, environmentally stable, and aesthetically eye-catching, it’s time to put this material back in the spotlight.

For a while now, architectural modernisation has been assessed through material and technology. Steel, glass and concrete have allowed buildings the world over to conform to a look that could place a structure anywhere in the world. In a globalised, mechanised environment, where machines make anything possible, the work of the hand, and the building blocks it can create, are often overlooked. But environments differ, lifestyles are varied, and separate regions possess different needs. Unique climates, special economic concerns, access to natural resources and energy, and intricate cultural traditions all inform the most optimal way to live.

By looking at vernacular architecture through the perspective of culture, tradition and climate, we can see that modern technology and new materials are not always the solution. Earth and clay, and the bricks that these materials become, are showing their significance in regions where harsh climates might necessitate more porous, ventilated structures, or where labour and traditional skills can be sourced from the community, creating employment and circular economies. Natural materials sourced closer to the projects they serve imprint an identity on a building that speaks to where it comes from. It shows where it belongs, and how it could probably exist nowhere else in this same way.

Hikma Secular and Religious Complex

In Dandaji, a village in arid western Niger, Mariam Kamara of Atelier Masōmī and Yasaman Esmaili of Studio Chahar transformed a derelict mosque into a library that shares its site with a new village mosque. They called on the expertise of the traditional masons of the original mosque to renovate the old building, imparting these skilled labourers with knowledge about adobe-enhancing additives and techniques for erosion protection in return.

Most of the materials were sourced within five kilometres of the property, and concrete was limited to structural elements such as columns and lintels. The main building material was compressed earth bricks (CEB), made with laterite soil found on the site. These CEB have resulted in a structure that requires less maintenance than adobe, but still retains similar thermal benefits. The resultant natural ventilation that emerges from the material has eliminated any need for mechanical cooling, making it a comfortable place for the community to gather and learn, even in the heat of the day.

Iturbide Studio

The studio of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide is a three-storey tessellated-brick tower on a 7x14m site designed by Mauricio Rocha and Gabriela Carrillo of Taller de Arquitectura in Mexico City. The repetitive, rhythmic brickwork encloses a central space with open-air patios on either side, offering natural ventilation, while the patterned uniformity of both horizontal and vertical bricklaying is another decisive control against the Mexican sun. Light emerges and retracts in a way that keeps the interior temperatures just right, while simultaneously texturing the home with shadows.

Such a contemporary use of traditional materials allows even the modern bookshelf to merge with the large clay volume of punctuated brick walls. This is a space designed to offer a sense of silence and an experience of continuity, say the architects. “An ethereal volume that disappears with the light and shadow… that stops being… so that the strong atmosphere – transmitted by this woman whom we admire – lives in it and is empowered.”

Casa de Marbel

Hundreds of families, left homeless after Mexico’s devastating earthquakes of 2017, received financial support from the country’s national disaster fund for the reconstruction of their homes. Many preferred to design and build these themselves so that they could spend more on materials. Such a situation, without the aid of professionals, would leave the quality of their homes compromised.

Architect Tatiana Bilbao was one of various architects who undertook a participatory design process with certain residents, ensuring an adequate exchange of knowledge about needs and technical possibilities so that results would be appropriate for the communities involved.

Casa de Marbel was one such home in the State of Mexico. The 86m2 property, surrounded by flowering trees with which the family makes wreaths to generate an income, had to respect its natural environment and resources. At the same time, it needed to be connected to house next door, where relatives reside.

This was managed by building three small volumes joined by platforms surrounding a central patio. Selected areas are ventilated by lattices made from compact earth bricks produced as ‘machimbloque’, a cost-effective method of construction in the area.

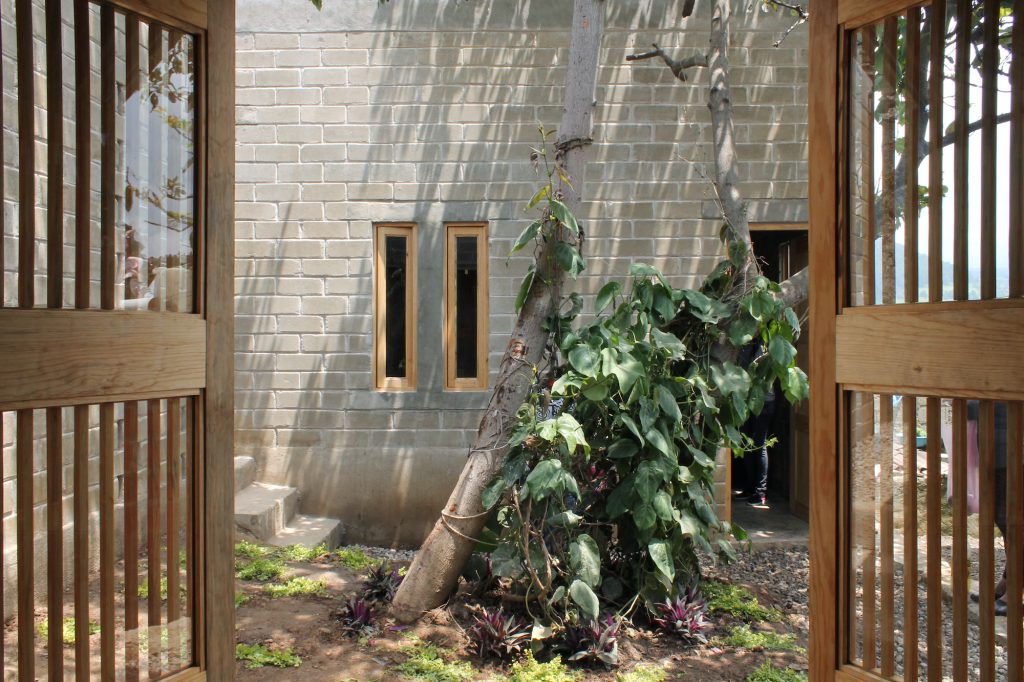

Long An House

A residence in Vietnam’s Long An Province has been designed by local architecture studio Tropical Space in a trapezoid shape that incorporates two storeys around a central courtyard and reflective pool. Inspired by traditional Vietnamese houses, the structure comprises three separate spaces and a sloped roof, and stretches across various functional areas that are divided by the intensities of light and shade rather than by partitioning walls.

Hollow clay bricks in the front yard absorb the rain and reduce the ground heat at the entrance, while indoor ventilation was maximised by dividing the roof into two parts, and installing a long corridor to connect the two sides and all the areas in between. The openness of the design, and the porous patterned brick walls, welcomes air into the home. Climate control is further enhanced by a clever layout that takes advantage of wind direction during different seasons of the year.

This article originally appeared in TLmag34: Precious: A Geology of Being

@atmasomi

@studiochar

@tabilbaoestudio

@tropical_space_architecture