Daniel Henry – Fibre textile

Swimming against the tide of the fashion and design market, Daniel Henry is a textile designer who trained at La Cambre Arts visuel. Following a year of research at the Tapestry Centre of Tournai – a city still marked by its history and time-honoured expertise – he has spent 20 years going where no one expects. During a meeting in his Tournai-based studio, simultaneously immersed in creation and production, between screen-printed fabrics, experimental embroidery and works of art in the making, Daniel Henry revealed his remarkably diverse path. He conscientiously weaves his canvas in a discreet and avant-garde way, by innovating new textiles – at once technical and artistic -, for the benefit of fashion designers and the textile, automotive and furniture industries.

TLmag: You began your fashion studies at La Cambre Arts visuels before branching off towards textile design. Why?

Daniel Henry: Quite simply, out of love of the material. In my second year, during a knitwear workshop, I realised I had found my path. What animates me is the sensuality of the material. For me, everything flows through touch. In the fifth year, I had the opportunity, while still finishing my studies, to collaborate on innovation projects for the European Confederation of Flax and Hemp. This first experience enabled me to create a network and to meet the players in the sector: from the spinner to the designer, by way of the knitter and the weaver. Almost 20 years later, my profession remains the same, but my requirements have changed. I try to be ever more radical in my choices.

TLmag: You had – and still have – the opportunity to work with the greatest couturiers. Tell us…

D.H.: My first fashion client was Christian Lacroix, for whom I developed finishes on silk and lace. During the same period, I was collaborating with Sébastien Meunier – the current artistic director of the Ann Demeulemeester label – on a denim for the men’s collection. I have always tended towards eclecticism in my choice of clients. Limiting oneself to the fashion sector never seemed very healthy to me. Today, I am also active in the automotive sector, in furniture, etc. One job leads to the next. Everything is constantly in movement.

TLmag: You even collaborated in the set design for Céline Dion in Las Vegas…

D.H. :I joined Franco Dragone’s team just after he left the Cirque du Soleil. We had to dress 65 members of the troupe. Our team was international. I worked alongside Americans, Mexicans…I also created contacts in Quebec that persist to this day.

TLmag: Was this experience a springboard for you internationally?

D.H.:Not really, in the sense that I never really worked for Belgian designers. The fashion brands in Belgium rarely have the budget to invest in fabrics like those I create… My fashion clients are thus mostly based in Paris.

TLmag: Two years ago, you decided to revise your way of working a bit. What have you changed in your approach?

D.H.:I was terribly frustrated by the rhythms of the fashion world. The sequence of collections makes it necessary to go faster and faster. In these conditions, it is nearly impossible to realise a substantive work. Even when I held the post of artistic director for textile manufacturers, I always had a tendency to involve myself in the research and development, despite the transgressive nature of this approach. Nothing is as exciting as developing new know-how.

TLmag: Could you give me some examples?

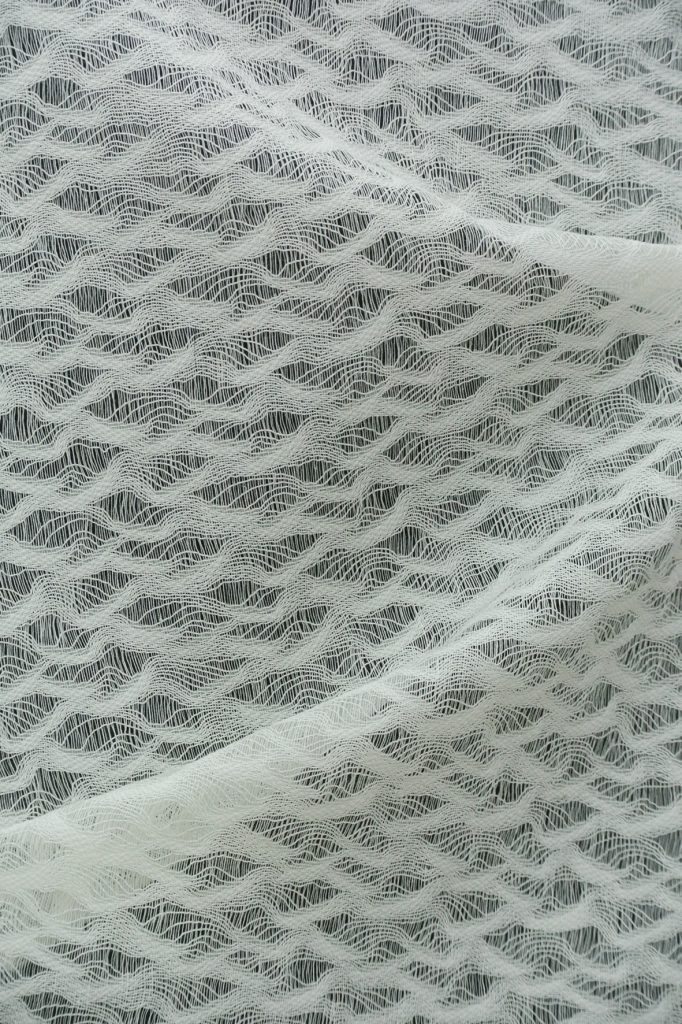

D.H.:In 2013, while I was working with lacemaker Sophie Hallette, I had the idea to combine a Calais lace with neoprene. It was very bold, and not everyone understood. To maintain a traditional feeling, I wanted to keep the toothed edge of the lace, but its rigid nature offered new design possibilities. That year, Chanel used it to make sleeves[KA1] for her show. Afterwards, I made a summer version of the concept by laminating a thinner lace onto Japanese paper. Giambattista Valli used this fabric to create a voluminous cape.

TLmag: What is your trademark?

D.H.: I like to transform old fabrics I unearth. They inspire me to new perspectives. Based on a starched linen I found at a flea market, I had the idea to create a structural print on a silk pongee. Then I made additional versions using this approach on other timeless materials in the masculine and feminine wardrobe (velvet, satin, chiffon). Once developed, this technique could be industrialised in Lyon by a small, family-owned business. The concepts of collaboration and transmission remain at the centre of my way of thinking.

TLmag: And do you also teach?

D.H.: I very regularly participate in ‘master classes’ in schools, and in conferences for industry professionals. I also train interns in the workshop.

TLmag: Does all this leave you time for personal projects?

D.H.:Very little, but I manage. This summer, I am taking part in Quebec’s Biennial of Linen, among others. I am exhibiting there as a visual artist. The 15 pieces I am showing (a mix of hand-embroidery, machine-embroidery and patchwork) explore the idea of a sublimated fabric cemetery. In October, I will exhibit in Liège at the Les Drapiers gallery, as part of Europalia. Inspired by Romanian skills and folklore, my work revolving around draping coexists with a very technical approach to gilding. I am not sure about the terminology for the part in yellow.