Dubai Design Week Makes Global Design History

The success of the second annual Dubai Design Week in 2016, and in particular the Abwab exhibition, will bolster the emerging call for more global design histories.

Modernist design history’s triumphalist narrative of progress emanating from industrialising Europe after 1850 is simply out of date,” writes Sarah Teasley, Giorgio Riello and Glenn Adamson in their co-edited book Global Design History. The book is foundational in the growing turn to examining design from a geopolitical perspective, which gained traction in 2016 through Alejandro Aravena’s Venice Biennale, a number of decolonising design initiatives, and perhaps surprisingly, Dubai Design Week.

The city with the tallest skyline in the world, Dubai has arguably driven more architectural innovation over the past three decades than any other place on Earth. Yet, since most of this was at the hands of Western starchitects, the boom did little to raise the profile of Middle Eastern architecture and design itself. International brand names and designers also joined the boom with the launch of Design Dubai Days in 2012, and Dubai Design District and Downtown Design in 2013.

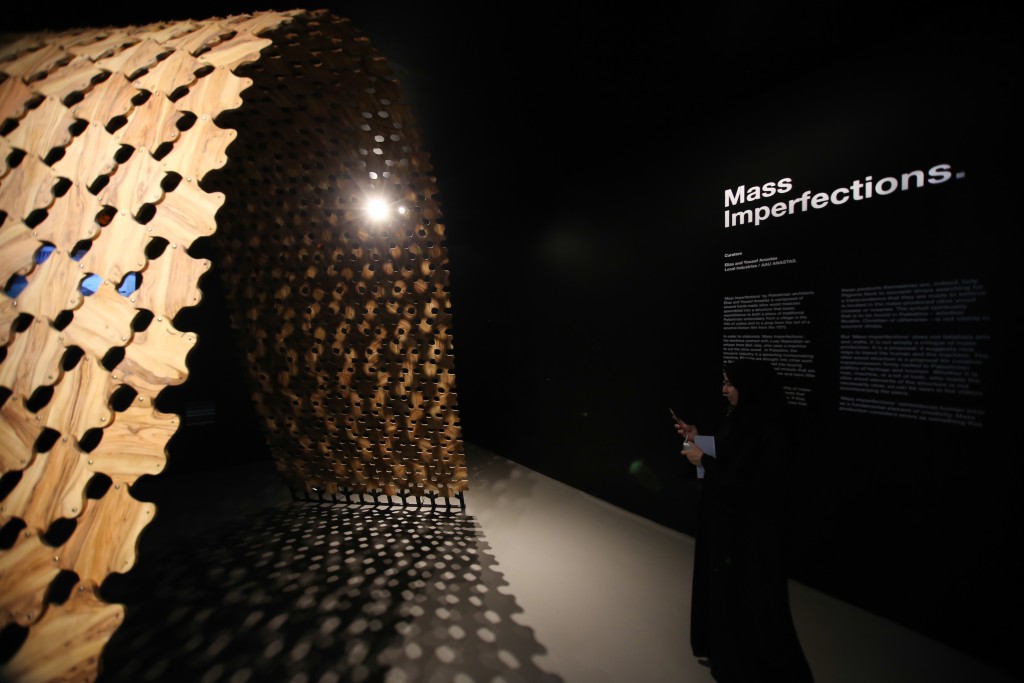

Now, Dubai Design Week has added another dimension by creating platforms to explore the MENASA region’s design identity and heritage without commercial pressure. With only the second annual iteration of Dubai Design Week in 2016, it is still early days. Yet already this strategy has resulted in a seminal first-ever survey exhibition of contemporary Egyptian design, as well as the more experimental Abwab exhibition.

Six countries were invited to participate in Abwab, named after the Arabic word for ‘doors’. While the theme was ‘the human senses’, each country’s exhibition is also a reflection on its own design identity. “Sat side by side,” explains Rawan Kashkoush, creative director of Abwab and head of programming at Dubai Design Week. “The ideas of each of the countries are emphasised. The exhibitions tell of their origins more clearly when we are able to read them all at once.”

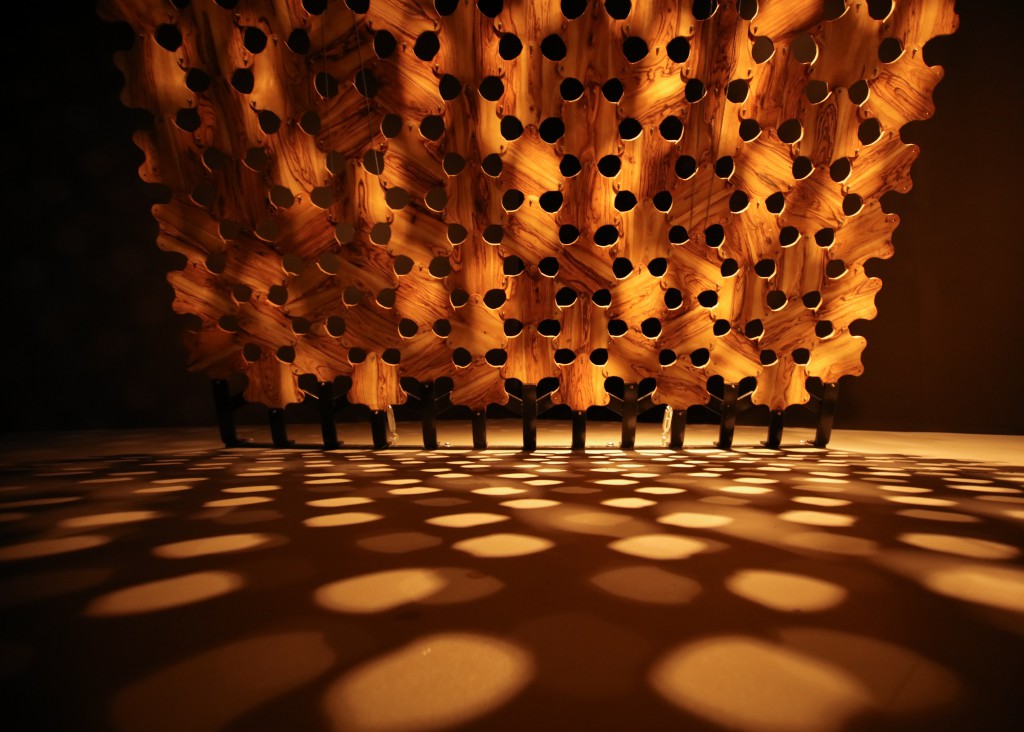

The United Arab Emirates pavilion, for instance, was inspired by the multiculturalism of the ubiquitous cafeterias. This is contrasted with the more archeological pursuits for identity, as seen with Bahrain, Iraq and Palestine. Bridging heritage and craft with the contemporary, were the interactive pavilions of India and Algeria.

Introducing this platform for self-reflexive and experimental design from the Menasa region is strategic for Dubai Design Week, which will hope to grow its significance through critical engagement. Given the event’s rapid growth, this my just be the platform and locality needed to start talking about a global design history that is “a methodology, one that acknowledges that design as a practice and product exists wherever there is human activity, on axes of time as well as space, and recognises the importance of writing histories that introduce the multi-sited and various nature of design practices,” reads Global Design History.

“Global design history begins from the conviction that knowledge is always fragmentary, partial and provisional, and only comes into its own through the unexpected challenges, confirmations, elaborations and unsettlings that result from encounter.”