Glass Magic: Breaking the Mould

On show at ‘Breaking the Mould’ is an awe-inspiring collection of kiln-blown glass artworks in all their wonderfully colorful and versatile forms

Smooth and rough surfaces, swirls of color frozen in time and mysteriously transparent and opaque forms await visitors of Breaking the Mould at Peter Layton London Glassblowing. This is the first comprehensive kiln-cast glass exhibition at the gallery since 2011 and shows the versatility of possibilities that this technique offers artists and designers.

TLmag caught up with Cathryn Shilling, an internationally renowned glass artist and the curator of Breaking the Mould to delve into the world of glasswork:

TLmag: Breaking the Mould exhibits glasswork that is made through the process of “kiln casting.” What it this and how does it work?

Cathryn Shilling: Kiln-cast glass is created by a series of complex and often lengthy processes. The simple definition is that in order to create a particular form, glass is melted into a mould in the heat of a kiln and then allowed to solidify.

There are several techniques that can be used but the most common is the lost wax process. The artist begins by making a form in a solid material that is then cast in plaster. From this, a wax model is made and invested in a refractory mould made from plaster and other materials. This type of mould retains its integral strength even at the very high temperatures required to melt glass. The wax is steamed out forming a void for the glass, hence the process is known as lost wax casting. The mould also has a reservoir that opens into the cavity and once in the kiln, this is filled with glass pieces or granules that when heated will melt and run into the cavity. Whatever the technique used to cast the glass, the cooling process can take from days to months depending on the size of the piece. Once cold, the glass often requires many hours of painstaking cold working – cutting, grinding and polishing – before its true beauty is revealed.

That sounds extremely time-consuming. Why do artists choose to work with this process?

Through kiln-casting, artists are able to explore the optical effects and physical properties of glass, making pieces about light and color as well as form. Cast glass has been around since Egyptian times, predating the development of glassblowing by the Romans, yet often overshadowed by it.

However, over the last three decades, there has been a rise in the use of glass as a serious artistic medium in the UK and kiln-casting has gained in popularity as a way of exploring artistic ideas. There is a tradition of teaching in the UK, with masters of kiln-casting passing on their craft. In Breaking the Mould there are both teachers and some of their former students included.

There seems to be a resurgent interest in the craft of glass, we have covered Venice Glass Week, the Douglas Vase by François Anzambourg and other glass exhibitions in the past few months alone. Do you think this is true? And if so why?

Until the middle of the 20th Century, most glassworks were produced in factories. The studio glass movement where the maker is also the artist or designer originated in America in the latter half of the century and, only recently, the 50th anniversary of the first glass workshops was celebrated. This movement has since spread and gathered momentum around the world, and glass has gained in popularity with artists due to its versatility and captivating qualities.

Could you tell us about London Glassblowing?

London Glassblowing has been in its present location for nine years now and we have seen a huge rise in interest of the art and craft of glass. Our workshop is open to the public and our audiences are drawn to the exceptional skill of our makers as well as the sheer beauty of the material. This interest is reflected in the increasing presence of glass at international craft and art fairs.

How did you select the pieces for the show apart from that they are all kiln-cast?

There is a thriving community of artists working in kiln-cast glass in the UK, a good number of whom are well known internationally. Through the exhibition, we wanted to highlight the versatility of glass as a serious artistic medium. Breaking the Mould includes a wide range of work, made from a variety of kiln-casting techniques from twenty artists working in the UK and includes established artists such as Angela Thwaites, Heike Brachlow, Bruno Romanelli, Joseph Harrington and Richard Jackson as well as new emerging talent such as Ingrid Hunter and Monette Larson. The work of several of the artists was included in the 2018 British Glass Biennale including Joseph Harrington whose piece ‘St Helens ii’ won Best in Show. We have also included work by a recent graduate of the Royal College of Art, Lola Lazaro Hinks.

From our own studio as well as Peter Layton’s pieces, we selected new cast work by two of our resident artists, Tim Rawlinson and Anthony Scala.

In my position, it is important to keep up to date with what is happening in the British glass scene, as well as internationally, which for me is a labor of love.

The works range from the figurative to the abstract, could you pick a couple of pieces in the show that you are particularly excited about and describe their stories?

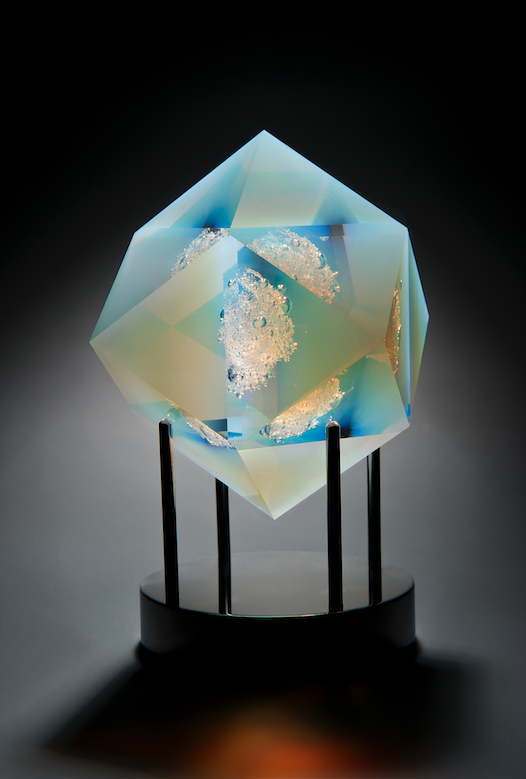

To select just two pieces from the wonderful array of work in the show is very difficult! However my first selection has to be ‘Particle’ by Anthony Scala, this is not just a technical masterpiece in its precision, but also a stunningly beautiful piece.

The interaction between viewer and piece is key, as you move around it, the initial appearance changes from cool white as it flickers red like a fire opal. I am constantly drawn to it as its character changes, from as brilliant as a diamond through to ethereal, in different lights. Anthony himself writes beautifully about this work:

‘This piece is a poignant reminder that there is far more to reality than what we can deduce from mathematical projections, simulations and raw data. Whatever the future of physics holds for our species, we can be sure that the fundamental nature of existence will be far stranger than any of us can possibly imagine.’

My other choice is Joseph Harrington’s impressive casting, St Helens ii, which Joseph recently revealed, took him four years to complete. Joseph has become a master of a process that he has developed himself:

‘I interpret landscapes through exploration of material. I focus on rugged coastlines, looking at erosion as a spectacle of discovery and generation of form, revealing a sense of the history and movement of a place. The work is produced using my ‘Lost Ice Process.’ I use salt to sculpt ice as a one-off ephemeral model to take a direct cast from. The textures this provides and the transient nature of the creative process reflects the erosion and sense of time I want to represent in the landscape. There is a roughness from the initial cast that is ground polished and refined to its final finish, revealing the internal structures of the glass and creating facets and flat planes to redefine the essence of the made against the organic surface.’

Breaking the Mould will be on display until October 20