Henry Van de Velde: An Unsung Visionary

TLmag helps tell the story of a shunned visionary in this interview with Werner Adriaenssens, curator of the Royal Museums of Art and History

Though a recent push to re-evaluate the life, work and influence of Henry Van de Velde has granted the Belgian designer iconic status, history has long dismissed this transitional yet controversial figure.

Overshadowed by his fellow visionaries in the various movements that he helped establish, the versatile autodidact was often relegated to marginalised roles. Although Van de Velde was integral to the creation of the Art Nouveau style, he was quickly eclipsed by Victor Horta. He also strove to expand and generate interest in the social consciousness that was first explored in neo-impressionism and William Morris’ Arts and Crafts movement. An idealist, Van de Velde felt that art had the power to shape society for the better. Thanks to his efforts, history now views Art Nouveau as the fin-de-siècle mitigation of industrialisation as it accelerated.

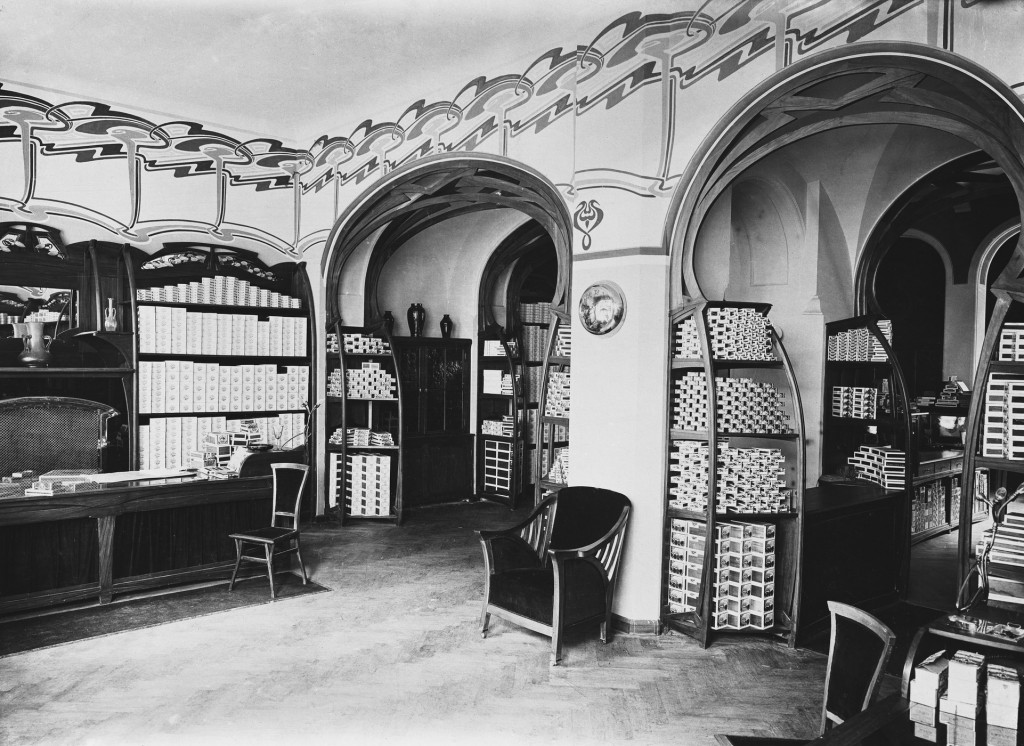

The designer was shunned in Paris as an unwelcome outside influence. Eventually in 1900, his competitors chased him out of Brussels. As early as 1914, given the rapid stylistic shifts taking place among the avant-garde elite in his adoptive Germany, Van de Velde’s work began to be seen as outdated. In a famous debate with the Deutscher Werkbund prophet Hermann Muthesius, Van de Velde stood firm in his defence of creative freedom, even when it took the highly un-modern form of ornamentation. His flowing interior and furniture design line, Whiplash, preserved its original context and was anything but frivolous. This nuance notwithstanding, Van de Velde’s opponent could only envision a future of further standardisation. This seminal stand-off would come to shape the century that followed.

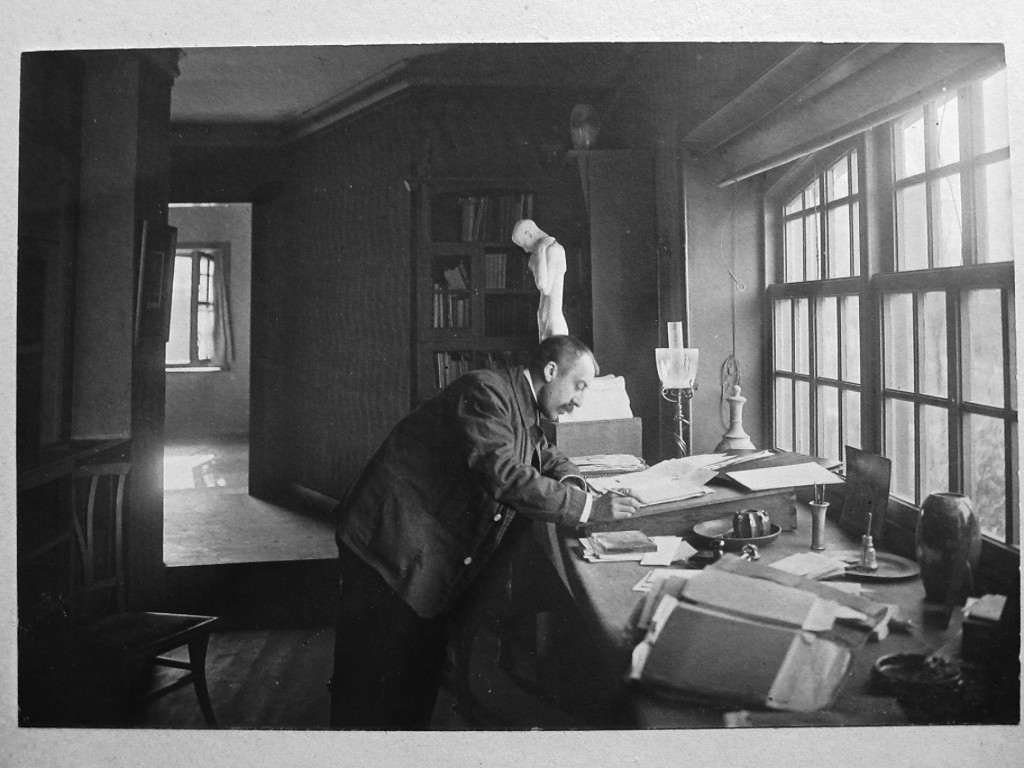

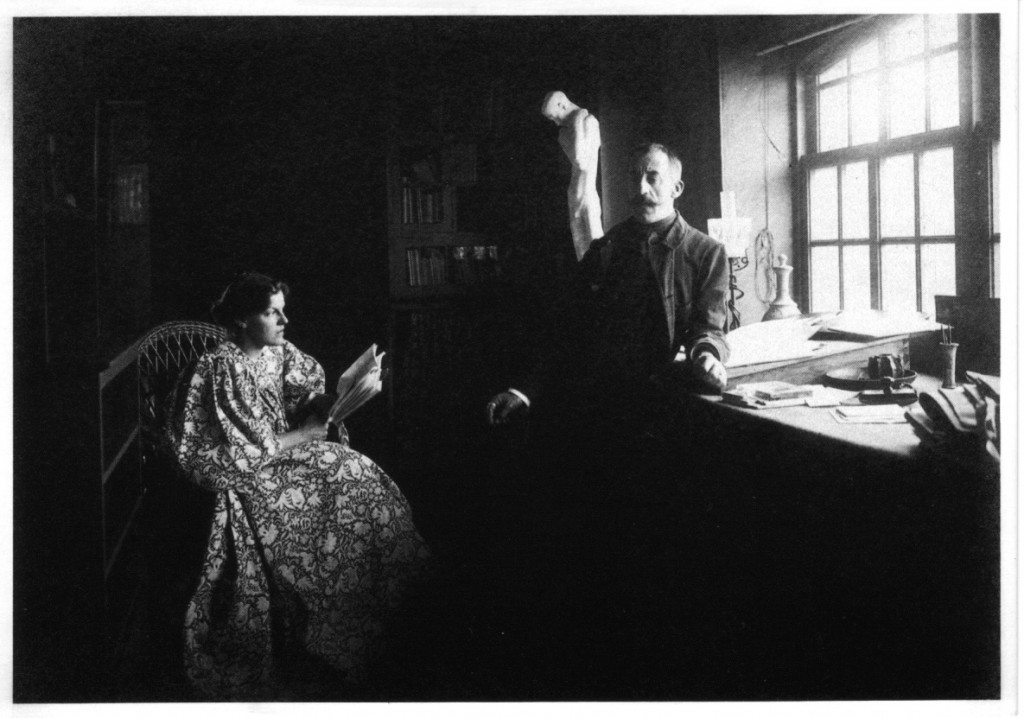

Van de Velde was undoubtedly a tragic figure. In the early 1930s, he found himself back in Belgium, where he shed his fragmented reputation and began to apply the new International Style. Despite his gloomy trajectory, Van de Velde’s legacy can still be seen in projects like the Havana Cigar Shop in Berlin, the Tropon poster, the Boekentoren at Ghent University, the Kröller Müller Museum and various transportation assignments. Perhaps the architect’s most symbolic work is his Bloemenwerf house in Brussels. TLmag helps tell his story in this interview with Werner Adriaenssens, curator of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels.

TLmag: Was Henry Van de Velde more of a craftsperson or artist than a designer or architect?

Werner Adriaenssens: It’s hard to categorise his profession. He was trained as a painter but was disappointed by the limitations of his skills. He idealistically viewed design as a new avenue. He completely stopped painting in 1893. Van de Velde had not studied the decorative arts and found that they afforded him more freedom and a better ability to shape his own approach. When he designed a chair, he concerned himself above all with its comfort and usefulness. Only then would he consider aesthetics. He designed Bloemenwerf as a functional space, not as a piece of architecture based on a set of rules. I would call Van de Velde a designer who was in constant evolution.

TLmag: Did he inspire a wider appreciation of art?

W.A.: Van de Velde was a child of his time: the late 19th century. The Arts and Crafts movement was bent on changing society in industrial England, close to Belgium. The movement adopted the slogan, “art by the people, for the people.” Though these ideas were utopian, they had a strong influence on the decorative arts. The problem was that over time, these designers ended up working exclusively for the elite class. Ironically, the new bourgeois believed in the ideals put forth by the Arts and Crafts movement.

TLmag: How was Henry Van de Velde different from other art nouveau architects?

W.A.: Since he was not an architect, he designed his buildings like they were objects. Since he was not restricted by his training, he had to learn from his mistakes and evolve over time. Horta’s impeccable techniques were a revolution in civil engineering. However, Van de Velde’s layouts were more daring and radical.

TLmag: What was the real reason Van de Velde left Belgium in 1900 and only returned 20 years later?

W.A.: Though Van de Velde was good designer, he was bad businessman. Having established his own Brussels-based workshop and firm in 1897, he solicited the financial backing of a German investor. He had already achieved some recognition thanks to an exhibition that was held the same year. Things fell through and the company was sold to the Berlin-based Hohenzollern-Kunstgewerbehaus. That was main reason why Van de Velde moved. However, being employed and working under someone else’s direction didn’t sit well with him for too long. When he moved to Weimar, he quickly lost the copyright for his own style. Horta helped to keep Van de Velde out of Belgium. He wanted to keep his competition at bay, especially as he was designing the Belgian Pavilion for the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. However, Van de Velde returned to Belgium in 1922 and became integral to the founding of the Brussels-based art school La Cambre. In doing so, he followed a model similar to the Bauhaus model. Over time, Henry Van de Velde

regained his position in Belgium.

Cover portrait: 1908 © Fonds Henry van de Velde, ENSAV-La Cambre, Brussels