Interview: Stefan Diez at MAKK

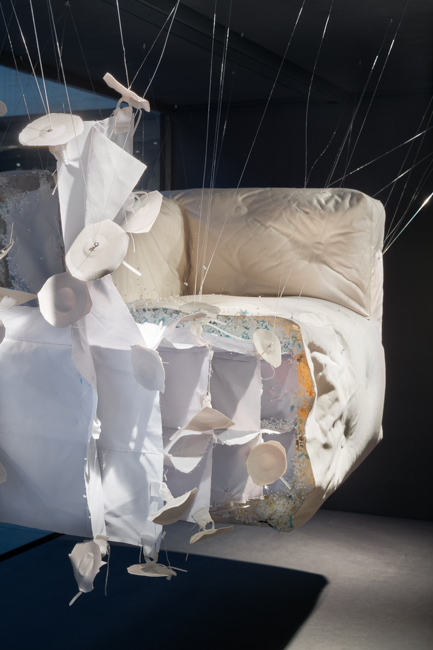

On the eve of Stefan Diez’s first retrospective, Full House at the Museum of Applied Arts Cologne from January 17 to June 11, TLmag asks him to reflect on his first 15 years as a designer.

“One of the greatest opportunities we have today is doing things together in an unexpected, experimental way by aligning mutual interests in a growing network,” says Stefan Diez. The Munich-based designer may be one of the most boundary-pushing industrial designers of our times, but he is a craftsman and teacher by heart. TLmag asks him to reflect on his first 15 years as a designer in anticipation of his first retrospective, Full House. The exhibition opens alongside imm Cologne on January 17 at the Museum of Applied Arts Cologne (MAKK) and runs until June 11.

Why the exhibition title “Full House”?

The title is a reference to the way I ideally see work and life together as a full and open house. It is also a reference to the way the exhibition was made possible: with the support of many hands in a huge collaborative project. I wanted to emphasise that one of the greatest opportunities we have today is doing things together in an unexpected, experimental way by aligning mutual interests in a growing network.

Much of your work crosses industry production boundaries – like making a chair using car technology. How and what drives you to make these creative leaps?

I believe every time we think about a new product or update an existing one, we should take into consideration the boundaries of what is actually possible. What can be done today that was not achievable a few years ago? This brings one straight to globalisation, outsourcing, digitalisation, networking etc. as driving forces of today. This context offers the possibility for the designer to influence how things are made and with whom.

What is your understanding of craft in relation to industrial design?

I approach many of our projects through the eyes and hands of a craftsman. Craft skills are powerful tools while creating shapes and balancing proportions. In many ways, craft helps to find the appropriateness a good product needs. And, last but not least, real models and mockups provoke communication within the studio, and with the client or partner. It is very simple to work as a team simultaneously on a mockup but very difficult to do the same in front of a CAD model. Of course we use the full spectrum of digital crafts in our studio (CAD, rapid prototyping, 3D printing, CNC routing, etc), but mainly for developing an industrially produced product rather than use craft itself as a means of production. This is because the effort we put into developing a product would only pay back in the context of mass production.

What is your philosophy and approach to teaching, in your capacity as a professor?

I have simply been lucky enough to be educated by some of the greatest enthusiasts in this field. I would be very happy if I could give back a bit of it. On the other hand, working with students is also learning for myself. I am not a full-time teacher, my engagement is rather doing a few projects over one year. It is simply a time conflict.

You’re presenting a phenomenal 15 years of work. Where to from here?

I think this period of preparation (the exhibition, the book) was a very important one for me. Many things got clearer while turning back and walking literally to the roots of where everything started – a bit like from the leaves to the trunk is only one way, but from the trunk to the leaves are many options – resulting in a much clearer idea of what really matters. I think this could be a good starting point for further projects.