Jean-François Declercq: A Blank Page

In 2015, collector Jean-François Declercq and his partner Elsa Sarfati opened a gallery Atelier Jespers in Brussels. For Declercq, Atelier Jespers is a new beginning – in many ways.

White, modernist house stands out in the quiet and stately residential neighbourhood in Brussels. Its curved corner with wide windows onto the street reveals a glimpse of the white, minimalistic interior. Unlike in the classical town houses in the area, the modest main entrance of the house lies in the end of a garden path, almost hidden in the corner of the house.

In the beginning, the house caused uproar in the classical neighbourhood for it’s perceived ugliness. Since then, it has been accompanied by buildings designed in the 1970’s and 80’s. Today, the house appears as an understated classic.

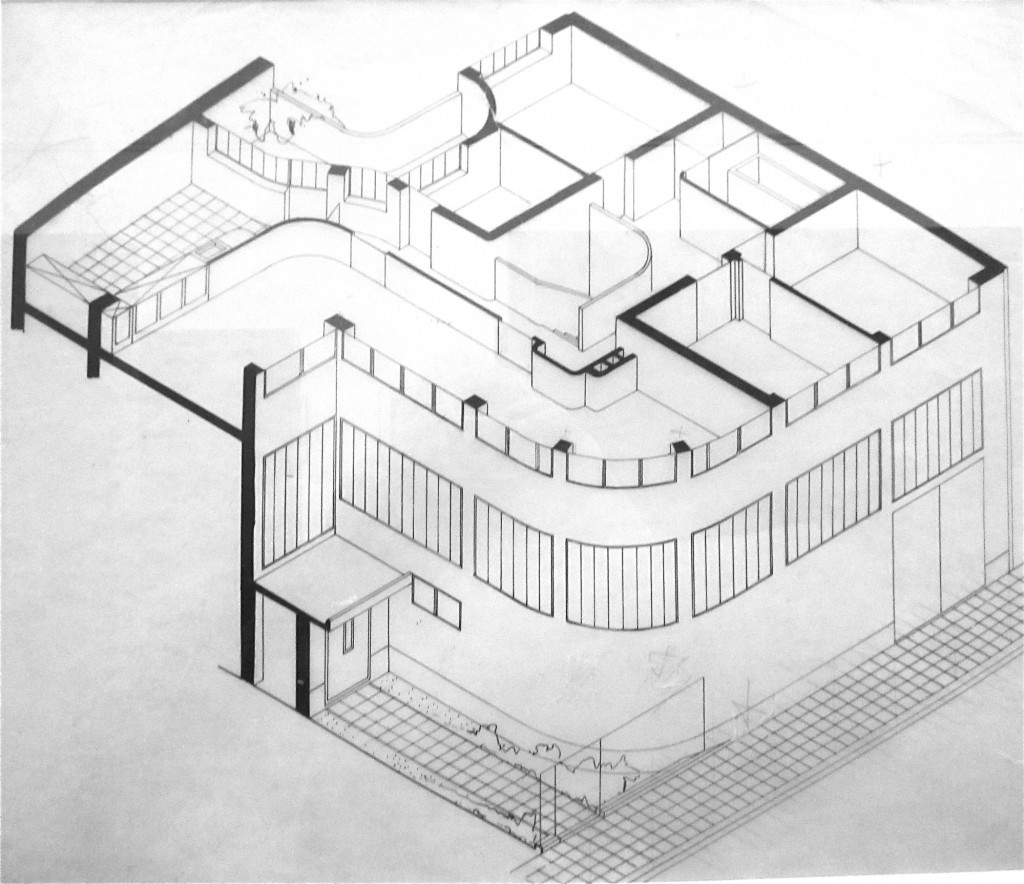

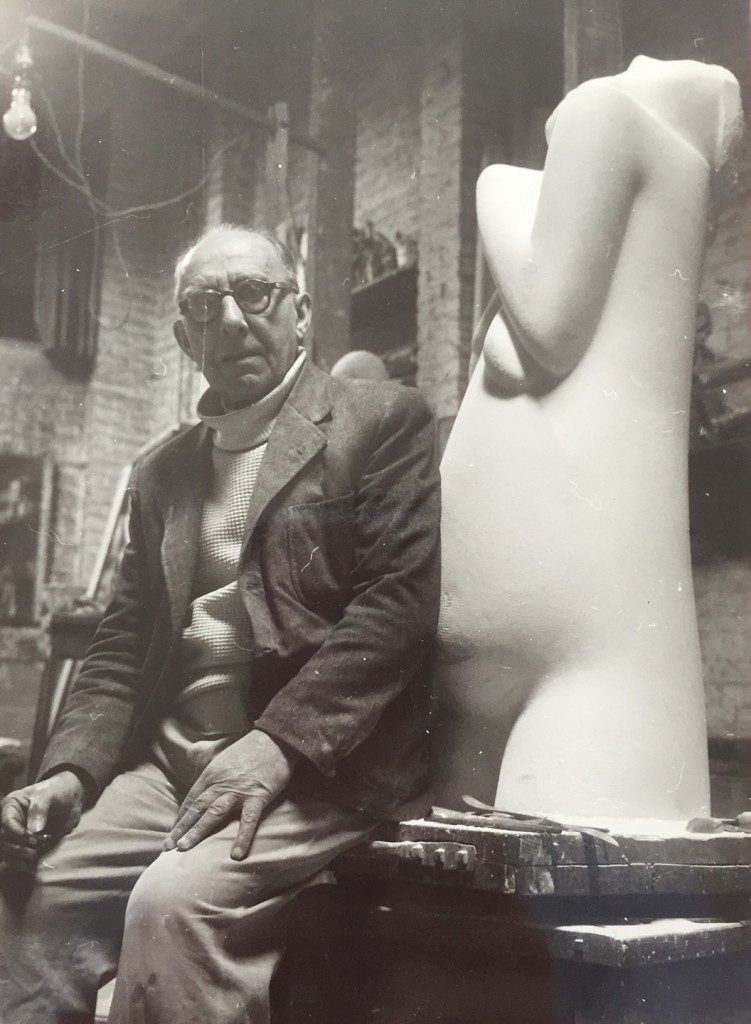

The building, Atelier Jespers, was designed by modernist architect Victor Bourgeois in 1928. The house was originally designed and built as a luxurious atelier for sculptor Oscar Jespers – luxurious in a sense that the vast open space that reached through the first floors of the building was completely dedicated to creating and showing Jespers’ art. He and his family lived in the 120 square-metre living space on the upper floor of the 400 square-metre house. After Jespers’ death, his family conducted an extensive renovation in the rather impractical house, and built floors and rooms to the atelier to make the house more liveable.

Two years ago, the house was bought by an entrepreneur and collector Jean-François Declercq. Used as a family house for a decade, Declercq lives there, but has also brought back one of the original functions of the house – exhibiting. He runs the newly established gallery Atelier Jespers with his partner Elsa Sarfati, with whom he also founded a Paris-based PR agency Page One, which focuses on art, architecture and design, in 2015.

Hoarding design

For a collector’s house, Atelier Jespers is surprisingly minimalist. The white walls are empty of art, the spaces echo, and there is only a rare collectible design piece here and there. The centrepiece of the entrance – the main atelier – is a contemporary large marble table by Antwerp-based designer Ben Storms. The table is accompanied by a rough, triangular bookstand by architect and designer Ugo La Pietra from 1970, and a contemporary stone table with a heavy tabletop balancing on a single point by Belgian designer Gerard Kuijpers.

Knowing that Jean-François Declercq is known for specializing and collecting architect Jean Prouvé’s designs, Atelier Jespers is strikingly something else than you would expect. Unlike Declercq’s previous home, which was a more typical collector’s home with rich colours and plenty of furniture and art, Atelier Jespers is exceptionally minimalist.

“I will put three pieces of art in the house, no more,” Declercq says. “I like things really minimal.”

That hasn’t always been the case. Declercq began collecting design as early as he could, eventually in the tender age of 18.

“I think I was 15 or 16, when I passed a typical 1980’s design store in a small town near France, and saw Philippe Starck’s Ara lamp. I stopped and thought: ‘what’s THAT?’ he tells of the first encounter with a design piece. “At that point, it was quite expensive for me, but when I was 18, I bought two of them. Since then, I’ve been really touched by design.”

“I stopped collecting during the period between ages 22 and 26–27, but at 28–29, my collecting became crazy and I bought a piece a week. I was chasing new finds every day. There was no Internet at that time, so I went to Paris at night and was the first one to enter the trucks bringing things to St. Ouen flea market. The trucks came at 2 o’clock at night and were opened at 5 am in the morning. I entered the trucks with a lamp; it was so dark that you couldn’t see anything. And when I found something interesting, I bought it.”

“That was in the beginning of my first company, and I bought things with every cent I could. But, I was sick – when one pile of lamps reached the ceiling, I started another pile. I had a huge warehouse for the pieces.”

“Then we were close to have a fire, and that opened my mind. Had the collection caught fire, I would have lost everything. That changed the way I bought, and I began focusing on things that I can handle in my place. I began to buy small things and I became a dealer.”

“Cured from collecting”

As life sometimes takes sudden and unexpected turns, Declercq and his ex-wife separated two years ago. She continued with their company, and Declerq bought Atelier Jespers and moved into the house.

“My life has changed a lot during the past couple of years,” he says. “Sometimes it’s been difficult to live the change but at the same time, if you work for it, it’s going to be very interesting and it will bring you more wealth inside. You really change your mind and begin to see things differently. It’s so rich. I’m quite lucky.”

Along the changes, Declerq sold the whole design collection he had collected during the past 15 years. The auction at Piasa auction house in Paris in May 2014 consisted of 90 design pieces from the 20th century, many of the pieces from designers and architects such as Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Perriand.

“Prior to the auction, I saw the pieces at home every day and kept thinking whether I will sell this or that. It was torture for me to decide what to sell. Then I just said ‘let everything go’ and so I was selling everything. The transport arrived, and we packed everything, everything. It was such a relief.”

“Every piece of furniture I had had a story behind. There was a Charlotte Perriand shelf for which I called the owner every now and then for seven years and asked if he would sell it. The guy said ‘no.’ And I called again: ‘Good morning, are you selling the bookshelf?’ Finally he sold it. For another Charlotte Perriand shelf, I received a phone call while doing groceries. I will remember that call for the rest of my life. I didn’t have money at that moment, ten years ago, and the guy gave me a week to find the 45.000 euro for the shelf. I sold my watches, two tables and a desk, and one week after, I bought the shelf. That was the most important piece of my collection.”

“In the auction, we sold a lot, almost everything, but I also discovered what was the real market. It was like selling a part of your life, selling everything you had chased for 15 years, something that was your fate… Some pieces could have been sold for more, but in fact, it was ok.”

Today, says Declercq, he buys only ten pieces a year, but the pieces are very high-end or rare. The role of the collected items has also changed, and Declercq is willing to sell a piece even if he liked it.

“Now I collect in a different way. At the time, I had to own the pieces. Now I see pieces without the idea of possessing them. No barriers, no frontiers, it’s open now. And, you know, when I say collecting is a disease – sometimes I went for a vacation only for two weeks instead of a month to provide me to buy things. Now I’m enjoying life more – living more than anything.”

“I’m now buying more from the brain than from the heart, and it’s sometimes better. I have started to find things from the 1980s interesting also. I quite like the aesthetics that was considered quite ugly ten years ago. When I see some Italian designers from that period, I get really interested about them. Two years ago I would have said ‘wow, it’s ugly,’ but now I’m looking for it.”

New beginnings

Seeing differently has also lead to collaborations that would previously have been unlikely – such as working on contemporary design.

“I still don’t see so many contemporary things I would like to buy though,” he admits, “although the InVein Marble table by Ben Storms hit me immediately.”

Considering Declercq’s fascination with 20th century design, contemporary Belgian designers Storms and Gerard Kuijpers were perhaps unexpectedly the first designers exhibited at Atelier Jespers in 2015. Coincidentally, the first exhibition in the atelier coincided with the 45th anniversary of the death of sculptor Oscar Jespers. Also coincidentally, both designers work on stone like Jespers did.

During BRAFA Art Fair in Brussels in the end of January 2016, Declercq and Sarfati will show a long-lost and recently found collection of furniture by modernist architect Georges Candilis. For Art Brussels art fair in April 2016, they will work with French furniture craftsmen and gallery Domeau & Pérès, and Atelier Jespers will also be one of the venues of the Art Brussels VIP tour. For this year’s Design September, the gallery will show a wide selection of Lampe Gras industrial lights from the 1920s, which, in Le Corbusier’s time, were used in nearly all of the buildings he designed as well as in artists’ homes and workshops. Once forgotten, the lamps were sold by no more than 5 euro in flea markets 20 years ago, and have since then been brought back to daylight and appreciation of collectors and design aficionados.

“Exhibitions and collaborations have appeared really naturally. It’s been easy. In the future, I think we will make some design exhibitions; some contemporary design, art and photography,” Declercq states with lightness in his voice.

Turning the house into an occasional exhibition space is, as the house is quite bare, relatively easy.

“We needed to move everything earlier last year for the exhibition, and now I have wanted to have the house pure like that. Some paintings are in my garage,” he says. “If you stay in the house long, you will discover details that remind you of a painting, for instance; a corner or circulation of light. The house is a piece of art in itself. If I lived in a white box, I would maybe like to add colour and all, but this house doesn’t need that.” •

Exhibition Georges Candilis, curated by Clément Cividino, at Atelier Jespers in Brussels, Belgium, on 22–31 January 2016.

Main image Jean-François Declercq.

Images Atelier Jespers, Brussels, Belgium.