Looking at Tiffany’s Stained Glass Windows in a New Light

The radiant, stained glass religious works of prolific glassmaker Louis Comfort Tiffany are brought together for the first time inside Richard H. Driehaus Museum’s historic 19th century Chicago mansion.

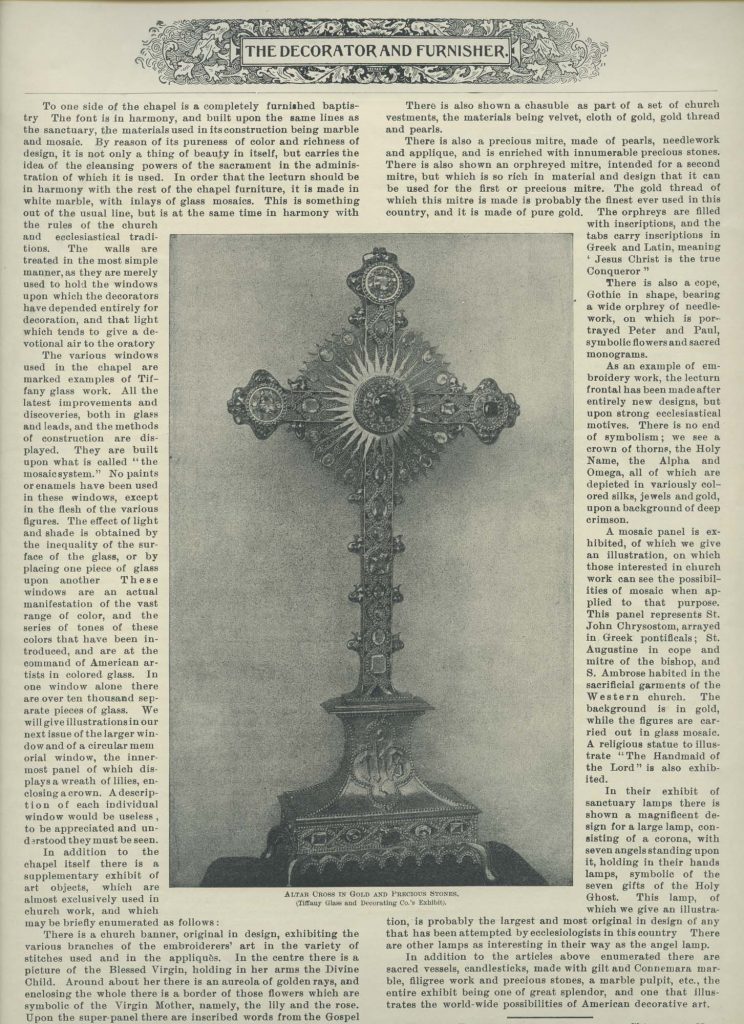

At the beginning of his career, it is said that Louis Comfort Tiffany (b. 1848 – d. 1933) used cheap jelly jars and bottles in his glassworks because they had the mineral impurities that finer glass lacked. When he was unable to convince fine glassmakers to leave the impurities in, he began making his own glass (Tiffany Glass) under the name Tiffany Studios in 1878 – which, at its peak, employed more than 300 artisans. Over the course of his life, Tiffany most notably redesigned the East Room, Blue Room, Red Room, State Dining Room, and the Entrance Hall of President Chester Alan Arthur‘s White House — and, as he focused on his glassmaking techniques, created almost anything out of glass from Tiffany lamps, jewelry and mosaics to stand-alone glass artworks and grand in-situ glass windows of spiritual nature. Tiffany’s inventiveness both as an entrepreneur, designer of windows and as a producer of the material with which to create them has made him renowned in and beyond his lifetime.

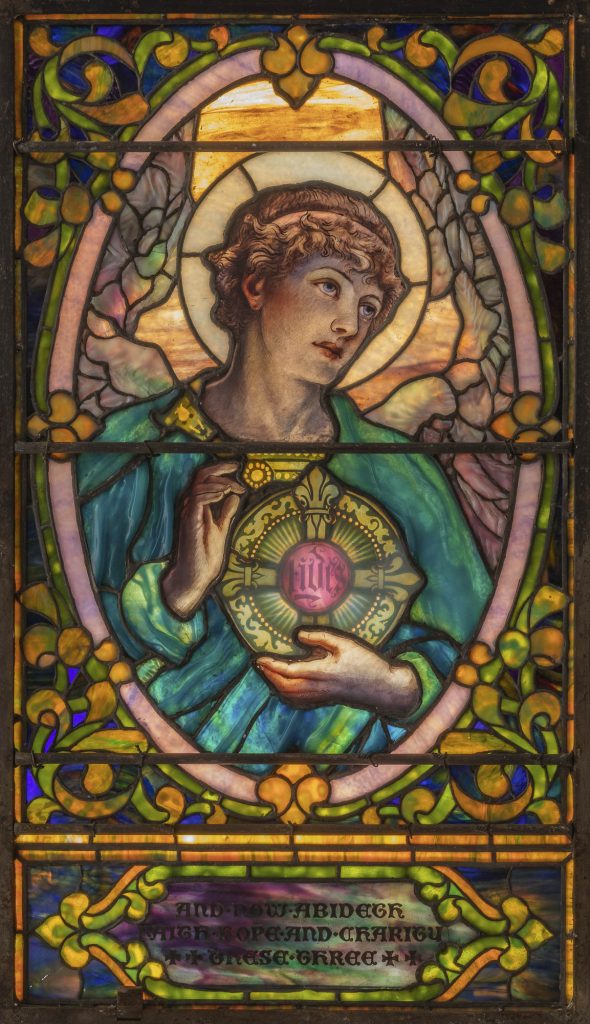

In an exhibition that opened early in September, the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago (USA) is housing 11 ecclesiastical windows made by Tiffany and his workshop artisans between 1880 and 1925. The exhibition, titled “Eternal Light, the Sacred Stained Glass Windows of Louis Comfort Tiffany” captures the artistic range and intricacy of Tiffany’s output, while drawing particular attention to his religiously-themed works as important signifiers of America’s rapidly shifting social, economic, and religious landscape at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

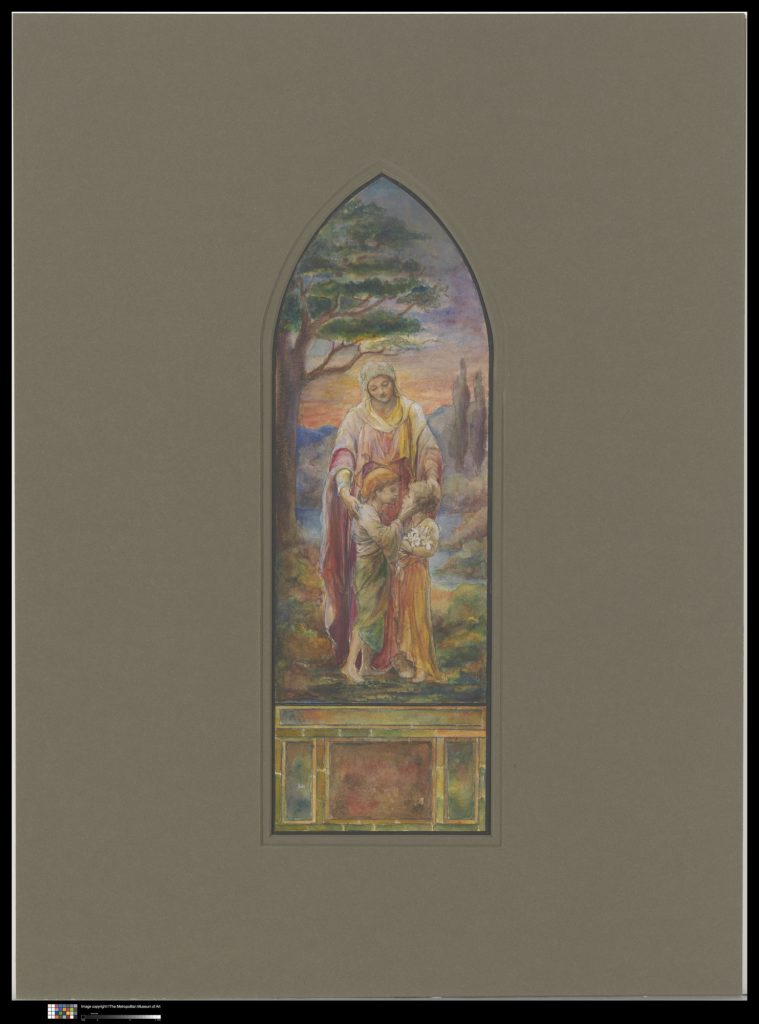

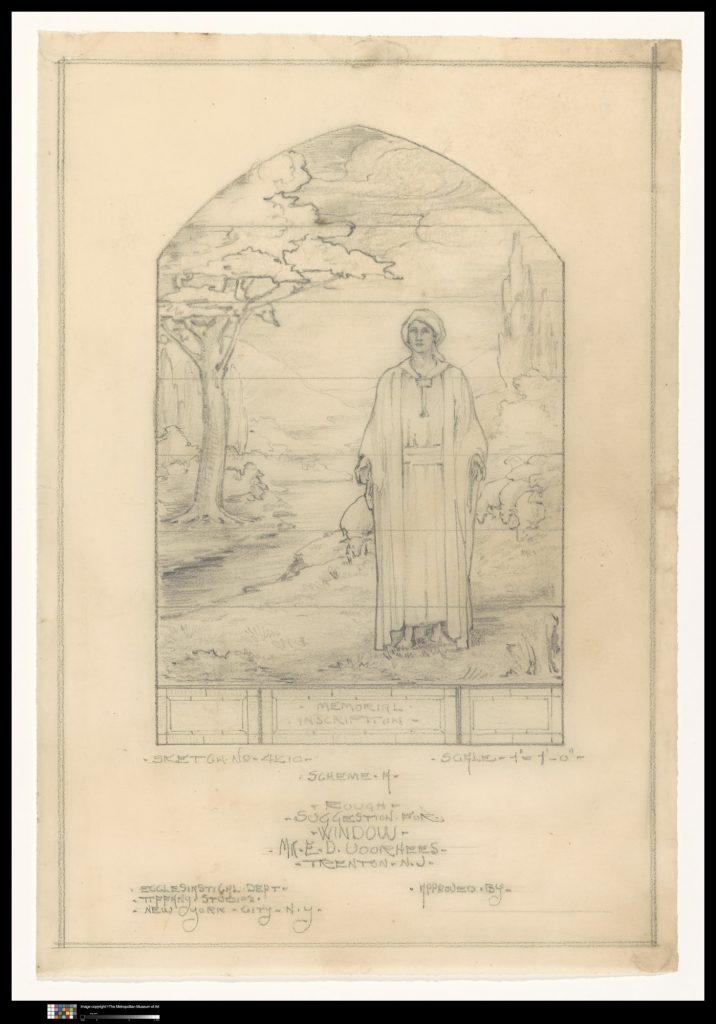

Divided into three sections, the exhibition examines the progression of an idea from design to finished product within the workshop’s Ecclesiastical Department, presents Tiffany’s marketing genius and his firm’s successful efforts to promote its services to Christian congregations and their patrons and, ultimately, presents ten stained-glass windows and one memorial chandelier that demonstrate the incredible creative and artistic glass capacities of the Tiffany Studios artisans. The windows included in the Driehaus museum’s exhibition are reunited with their preparatory drawings for the first time in over 100 years since they were created — and are also exhibited alongside other archival materials which highlight Tiffany’s incredible creative and commercial vision and provide a new opportunity to examine him as a key purveyor of America’s modern future.

To further contextualise the prominence of Tiffany’s religious works and to accentuate his impact on Chicago’s art and architecture, the Driehaus Museum has also organised a 14-stop interactive self-guided tour through the city. The tour, titled Chicago’s Tiffany Trail, will build on themes explored in the exhibition and provide details on the patrons who commissioned the projects, the technologies used to realise the designs, and how each Tiffany work is incorporated into the architectural design of their environment.

“Eternal Light looks without sentiment at the ecclesiastical windows of the Tiffany firm as rich reminders that America is ever-changing,” said Richard P. Townsend, Executive Director of the Richard H. Driehaus Museum. “Tiffany’s masterpieces tell stories of American entrepreneurship, of places of worship as community incubators, of our country’s evolving relationship to religion. This exhibition is not only about beautiful objects exceptionally crafted, it is also about the ideas and stories behind the windows: progressive technologies, designers, and patrons.”

“Eternal Light, the Sacred Stained Glass Windows of Louis Comfort Tiffany” is on view at the Driehaus Museum until March 8, 2020.

Cover Photo: Tiffany Glass Company, American (1885-1892). Designed by Frederick Wilson (American,born Ireland, 1858-1932). Christ and the Apostles, ca. 1890. Leaded and enameled glass. The Collection of Richard H. Driehaus, Chicago, 40012.a. Photograph by Michael Tropea, 2018.