Mounir Fatmi – Archaeology of Materials

At the Göteborgs Konsthall, Mounir Fatmi considers the importance of materials as a tool for the future understanding of our present modes of technology and communication.

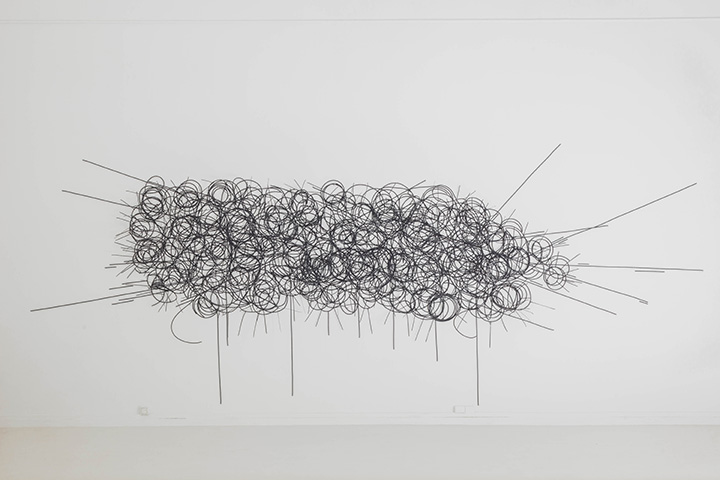

What happens to the empty recordings on abandoned VHS cassettes? Does a transmission cable still transmit information if not used as intended? What are the limits of language? Using materials like old typewriters, cable wire, and massive printing presses that no longer function, Mounir Fatmi questions the limits of language and communication, while also reflecting on the material itself and its uncertain future. There is something of the archaeological spirit behind some of the work presented in his recent exhibition, 180º Behind Me, at the Göteborgs Konsthall from August 6 to September 16. Nearly all of the materials on display, as they exist now, will disappear in the future, and his artwork and installations will be an archive, a point of research for understanding our times as much as the exhibition and the meaning of the artwork itself.

Liv Stoltz, curator at the Göteborgs Konsthall, and visual artists Mounir Fatmi discuss the exhibition and Fatmi’s practice:

Liv Stoltz: You often use anachronistic material in your work such as old VHS tapes, type-writer machines, copy machines, electric wires and printing machines; and build them into large installations. Two examples of this are your pieces Black Screen, a wall consisting of VHS tapes, and The Index and the Machine, which is an old printing machine from 1872. Why do you integrate this kind of antiquated technology that is in some sense “useless”?

Mounir Fatmi: I like the fact that you started this interview by using the word “useless”. What is useful, anyway? Is a work of art useful? And to whom is it really useful? At the very beginning of my career, when I was still living in Morocco, I was always fascinated by those useless materials you listed: antenna cables, VHS tapes, obsolete typewriters. In a way, all these objects reassure me. All these archaic technologies express the end of something, a moment in our history. Most of all, they are about death. A great deal of my work consists of reanimating them, or rather accompanying their mutation from useful objects to useless ones and ultimately to simple archive documents. An African mask in a Dogon tribe is useful, initially. The same mask thrown in a museum loses its function completely.

LS: The political theorist Hannah Arendt’s quote, “There are no dangerous thoughts, thinking itself is dangerous” has been important to your work with this exhibition at Göteborgs Konsthall. How has this statement influenced this specific exhibition? And, beyond this exhibition, how has Hannah Arendt affected you personally and your work?

MF: The Hannah Arendt quote pinpoints the very problem of what it is to “think”. It’s an act of resistance, of revolution even. I wanted the public to have that sentence in mind before they went in to see the exhibit. I wanted them to understand that thinking is a political act, and not a gratuitous and useless act. Many philosophers have inspired my work, not just Hannah Arendt. I could mention Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. I have always used philosophy to understand the world in which I live. Philosophy to me is like a toolbox: I know there is always a hammer in there for breaking walls.

LS: You place a particularly high value on words. You integrate words, phrases and Arabic scripts into many of your works as well as other communicators of language; such as flags, VHS tapes, speakers and typewriters. With this in mind, can you tell me about your interest in languages and the written word? From where does this emanate and what does it mean to your practice as an artist?

MF: Wittgenstein compares the question of language with the question of limits. He says very simply: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” I use language in some of my works to accentuate even further this effect of limitation and failure. Just because you look at a picture of a chair with a little sign that says “chair” doesn’t explain anything. Lévi-Strauss went to great lengths to try and understand what “to signify” really means. Unsuccessfully. Language is the first of our illusions of communication, it’s our limit, and I use it specifically for that reason. The last sentence in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus logico-philosophicus says: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

LS: Critique of ideology, consumption and dogmas are all important motifs in your work. Can you tell me of your interest in these topics and how they influence your work?

MF: Ideologies, dogma, religions, consumerism, etc. are put in place primarily to prevent us from thinking. That’s why thinking is a political act. And what else can we do than criticize them and even look for strategies to deconstruct them? My critical work attacks precisely this trinity: architecture, language and machine. These three “concepts” are interrelated in the fact that they serve all the installed power and the dominant thought. What I call “ready to think.” It took me a long time to be accepted as an artist dealing with political, religious or simply social topics. If you do a quick little search, you will find that most artists who declare themselves politicized are a minority and they often come from countries with very serious political problems. I think that my artistic sensibility comes rather from my daily reality, because I am Arab, Muslim, African, third worldist, feminist… that of my studies at the School of Fine Arts in Casablanca or the Rijskakademie in Amsterdam. So, I came to this idea that we cannot change the world without changing the concepts that make it work. I do not think we have other choices.

LS: Your work centers on the meeting points as well as the frictions between East and West and the intermingle between ancient traditions and hyper modernity illustrated in your images of machinery. What relationship do you have to history and the interpretation of history in relation to contemporary times?

MF: To answer your question clearly, my work can be seen and read in many ways. It is because there are frictions between East and West that my work is seen as a meeting point between them. Yes, there is a conflict between ancient traditions and hyper modernity, you can see that in most of my works. I do not stop going back or accelerate in time. It was not easy to integrate Arabic calligraphy for example in contemporary art. When I started using it, it shocked many of my artist friends at first. It’s like I’m no longer contemporary. I’m not interested in our time. What interests me is the history, even though I tried very hard to break free from my history and from history in general. I think that we are prisoners of what we have called contemporary times. Until when will we talk about contemporary times since we live in contemporaneity every instant? Do you think that one day, we’ll wake up, turn on the radio to discover that: “Finally, we have just come out of contemporary times!” More seriously, I believe we all live trapped in a very narrow space-time with a very limited body and intellect. We are here because we don’t know yet how to go anywhere else. And in this prison of “here and now,” there are some who try to find a breach in the wall and escape. And others who have accepted this state of things and begin decorating the walls. And even add more cells.

LS: There are very strong aesthetic dimensions in your work. What does this visual beauty of your work mean to you? Do you feel that there is a risk for the visual impact masking the often strong political aspects of your work? How do you see these dimensions interacting with each other?

MF: As I have said: my works of art are esthetic traps. Without esthetics, no one would go and see the different levels of my work. I always wanted to control the illusion that is esthetics. I try and create a work within another, a sort of camouflage. Sometimes it takes a lot of time and effort for the audience to appreciate my work or to understand it. I often say there is nothing random in my work. That I control every aspect down to the last millimeter, even when I create an accident. And that the result of that accident is mine: despite the fact nothing proves this to me. In the end, in order to continue to create, I hopelessly try to control my disappointment. With time, my visual language, although it’s doomed to fail, attempts to point the public to that idea.

Mourir Fatmi Instagram : @mounirfatmiofficiel