Perspectives Shift in WIELS and TANK Shanghai’s “Convex/Concave”

In a city about 9000 km away from where they’re based, Brussels art centre WIELS collaborates with the recently opened TANK Shanghai in an exhibition that reflects on the dualistic nature of Belgian contemporary art and culture.

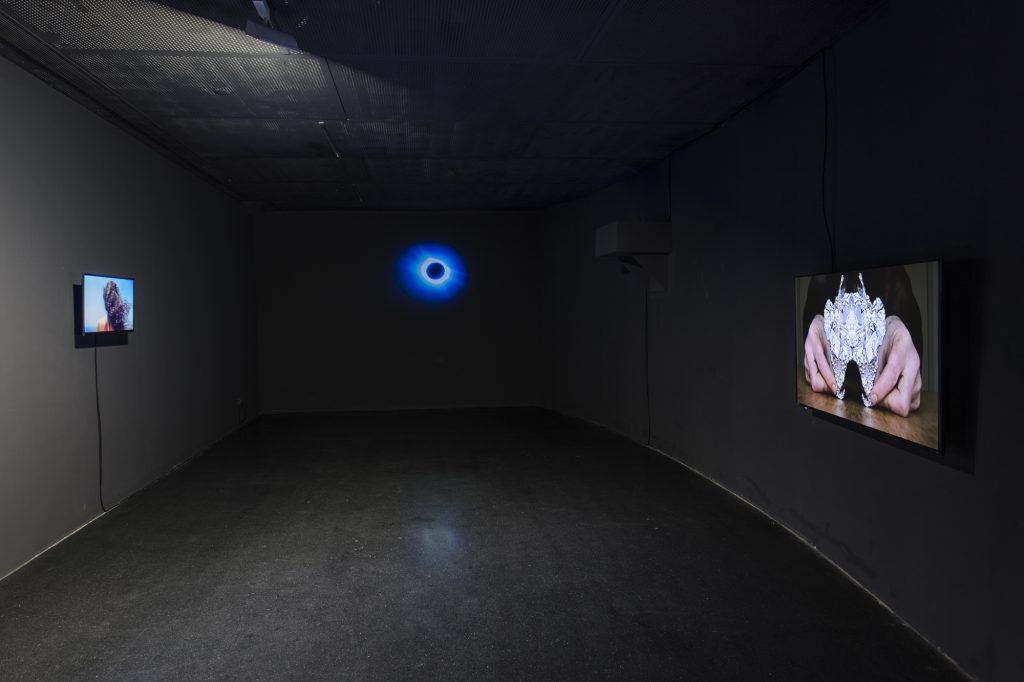

Featuring 15 contemporary (from internationally renowned to emerging) Belgian artists, “Convex/Concave: Belgian Contemporary Art”marks the largest exhibition dedicated to Belgian art in Shanghaiever.The venue where it’s taking place,TANK Shanghai, is the brainchild of Chinese collectorQiao Zhibingand was only opened in March earlier this year (2019). The 60,000 square meter complex (the size of 11 American football fields) has turned former oil storage tanks for the Longhua Airport into galleries, a bookstore, a café as well as an education centre.WIELS, a leading institution for contemporary art in Europe in its own right, is known for its continuous temporary exhibitions without a permanent collection — and has, since its opening in 2007, presented more than 65 shows. The main title of the exhibition,Convex/Concave, conveys terminologies referring to the converging or diverging of light through lenses in a reframed cultural setting. The somewhat ambiguous title reflects on internal contemplation and openness to those beyond our own selves — a dualism that, according to WIELS curatorsDirk Snauwaert(who is also WIELS’s director) andCharlotte Friling,can be found in both China and Belgium. TLmag sat down with co-curator Charlotte, to learn more about the detailed works on view and the process leading up to this special exhibition.

TLmag: What was the drive behind producing this exhibition, and collaborating with TANK Shanghai?

Charlotte Friling (CF):We felt that the exhibition could be a kind of cultural and intellectual exchange between Belgium and China. We wanted something representative, and so the base of the show was that we asked the selected artists to choose iconic, truly representative works of their practices. For us, it was also a way to be able to work with artists that we haven’t had the chance to work with yet. We also felt a connection to TANK, as we share a kind of similarity in the goals we set and type of program we want to present. It’s a new institution in Shanghai and to be able to be associated with their energy and ambition was really interesting for us.

TLmag: TANK Shanghai is a huge space. Is building up exhibitions in such big areas more or less of a challenge?

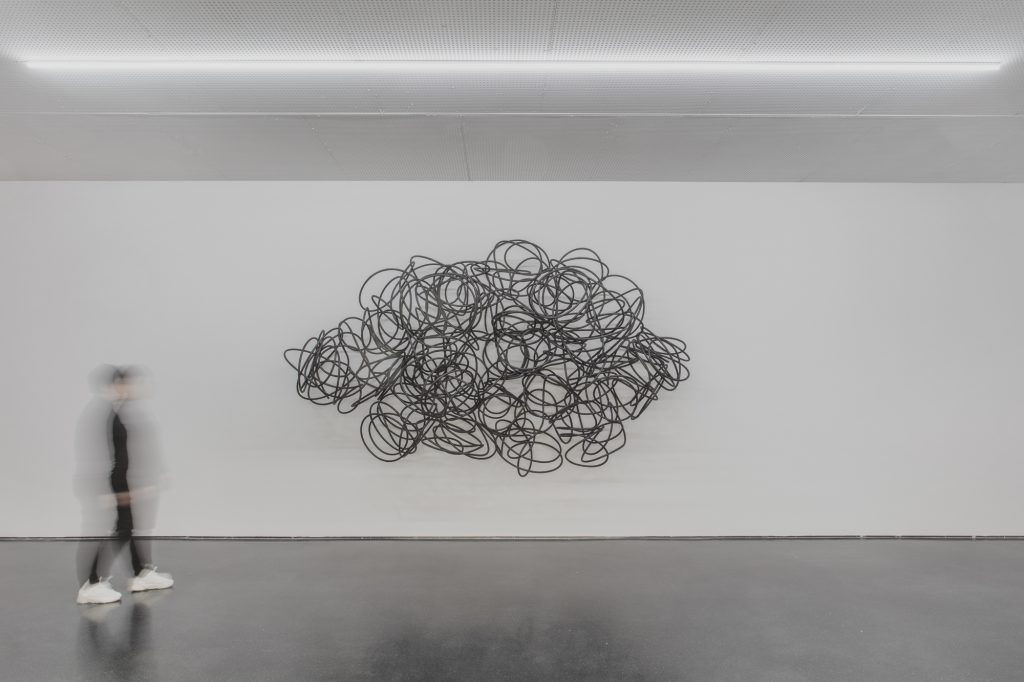

CF: The spaces provided to us were great, but I admit they were also rather tricky; we had two gallery-like floors in one of the tanks, as well as the large entrance hall — which is very much open to the outside and a place of transit. At first, we thought of giving each artist their own space, but eventually the works ended up in closer dialogue with each other than we expected. As a result of that, most spaces developed very particular energies — and introduced completely new perspectives to existing works. Artist’s works who probably would rarely be associated in another context were placed alongside each other such as for instance a large sculpture by Berlinde De Bruyckere, paintings by Jacques Charlier and an installation by Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys. The parallels that we’ve drawn there were ones we wouldn’t have seen otherwise, and it was great for us to have that freedom over there.

TLmag: How was the collaboration with TANK Shanghai? Did Qiao Zhibing have any influence on the exhibition beyond the show space? In the artist selection, for example?

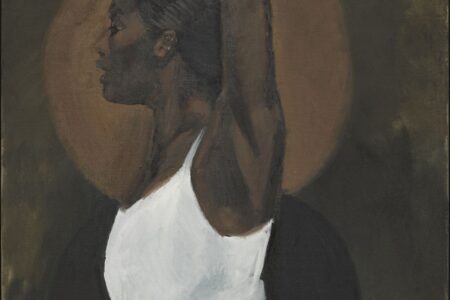

CF: They had total trust in us, and really let us do our own thing. Because Qiao Zhibing’s entry point into contemporary art was collecting works by the likes of Michaël Borremans, we did feel like that would be an excellent point of departure for the exhibition. Working with him and maybe other more famous Belgian artists would provide a base to attract attention and allow other artists, who were more mid-career, to share that spotlight.

TLmag: Curating a show with solely Belgian artists in Shanghai, and having it be the largest exhibition dedicated to Belgian art there up to this point in time, is quite a daunting challenge I imagine. How did you go about connecting 15 artists, each with their own practice and methodology, within this group show in China— and represent the types of contemporary art being made in Belgium without over-simplifying it?

CF:As a response to this exhibition,a lot of people have been asking us what Belgian art is, or how it differs from Chinese art. It is evident that there is no static definition of Belgian or Chinese art, and that this exhibition simply aims at showing a certain angle from which our own rich art scene can be approached. What’s more, we’ve had the opportunity to visit artist studios and exhibition spaces in Shanghai, and have discovered a great diversity of practices that we can relate to and that show more synergies than differences between our countries and cultural scenes.

Regarding the artist selection — fifteen artists is a long way from representing what Belgian art or artistic production in Belgium is, and it was an extremely difficult choice to make. There were many many more artists that we would have liked to invite but, because we wanted to give every artist their own space and importance in the show, we felt that it was more interesting to limit the number of voices, instead of trying to be too widespread. Something that we noticed (and that we built this show around) is that in the artists we selected there was a tendency to work either in a way that was very extroverted and interconnected, or, reversely, in a more intimate and inward-looking way. That’s the tension that resonates in the title “Convex/Concave”, two different reactions to the reality of our world today.

In general, we’ve shown more recent work than older work, and that was also our intention; we didn’t want to make a historic show, but a show that is grounded in what contemporary artist are making now.

TLmag: Alongside existing works, the exhibition also shows site-specific installations — right?

CF: Yes, site-specific and specially made works that reflect how interested the artists were in collaborating and responding to the Chineses context of this show. Michaël Borremans made three new paintings for us, Koenraad Dedobbeleer, Harold Ancart and Edith Dekyndt developed entirely new works and Luc Tuymans managed to find nine paintings — resulting in a spectacular kind of mini-retrospective. A really major site-specific work outside by Sophie Whettnal took the shape of a performance as the artist spray-painted shadows of non-existent trees on the ground in front of the entrance to TANK as an echo to Chinese landscape painting. Also outside is Ann Veronica Janssens’ reinterpretation of one of her major works in neon, which says “the order has no importance” in jumbled up letters. It’s an incredible work in public space, and we’re fortunate that it went through, especially knowing that censorship is very tough in China. When you think of that sentence, “the order has no importance”, specifically in the country today — it sends a strong message.

TLmag: What has been the biggest challenge in the run-up to Convex/Concave?

CF:What took us longest was finding the financial means to do this exhibition, and we were very lucky to have the support of the different communities in Belgium, as well as of the artists, certain galleries and generous sponsors. It took us a long time and, honestly, until pretty late in the project we weren’t even sure if it was still going to be able to happen, especially now with so many cuts to funding within the arts. Having said that, these struggles make you really get to the core of your project and make it stronger. It makes you think about why it’s essential to do a show like this now, not only for WIELS but for the artists and for Belgium too.

TLmag: And was the reaction from the audience what you expected?

CF:The feedback from Shanghai and from colleagues from all over the world who got to see the exhibition has been extremely positive and we’re very grateful for this. For many, it was quite a revelation, through the diversity of voices that we presented and the quality of the works featured, always careful not to fall into any shortcut or cliché of what one might think of as ‘Belgian’. Some of the artists that we brought were already quite known from the art world over there and attracted the initial attention, which allowed lesser-known artists in the group to really be looked at and considered at the same level of importance. The curiosity and professionalism of the TANK team and their mediators were also instrumental in bringing this show very close to their audiences.

TLmag: What was it like for the artists?

CF:We were lucky to have seven out of the fifteen present for the setup and the opening. As none of them knew TANK, some were a bit nervous about space – but that soon disappeared as each managed to perfectly balance their work in the space. It was also great to see some of them meeting each other for the first time, even as Belgian fellow artists! It became a space for new exchanges. A lot of them were also really inspired by what you could do, see and get in Shanghai, and by direct responses from the audience to their contributions. It’s another, fast-paced world over there — everything is extra large and complex, everything seems possible, while at the same time contrived and closely monitored, and so it was a unique experience for all of us to be able to experience that from the inside.

TLmag: Is there anything that you’ve learnt from curating this exhibition that you’d like to take incorporate back at WIELS?

CF:I think we’ve taken some curatorial risks there that should inspire us for our program here in Brussels, being off the beaten track and adventurous to perpetually reinvent ourselves.

“Convex/Concave: Belgian Contemporary Art” will be on view at TANK Shanghai until January 12th 2020, and includes works by Francis Alÿs, Harold Ancart, Michaël Borremans, Jacques Charlier, Berlinde De Bruyckere, Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys, Koenraad Dedobbeleer, Edith Dekyndt, Michel François, Ann Veronica Janssens, Thomas Lerooy, Mark Manders, Valérie Mannaerts , Luc Tuymans and Sophie Whettnall.