Rotor: Archaeological Practices Applied to Architecture

Rotor is shifting perceptions of how buildings are torn down and reassessing the manner in which they rise, taking a critical look at the industry and challenging notions of “new” being better.

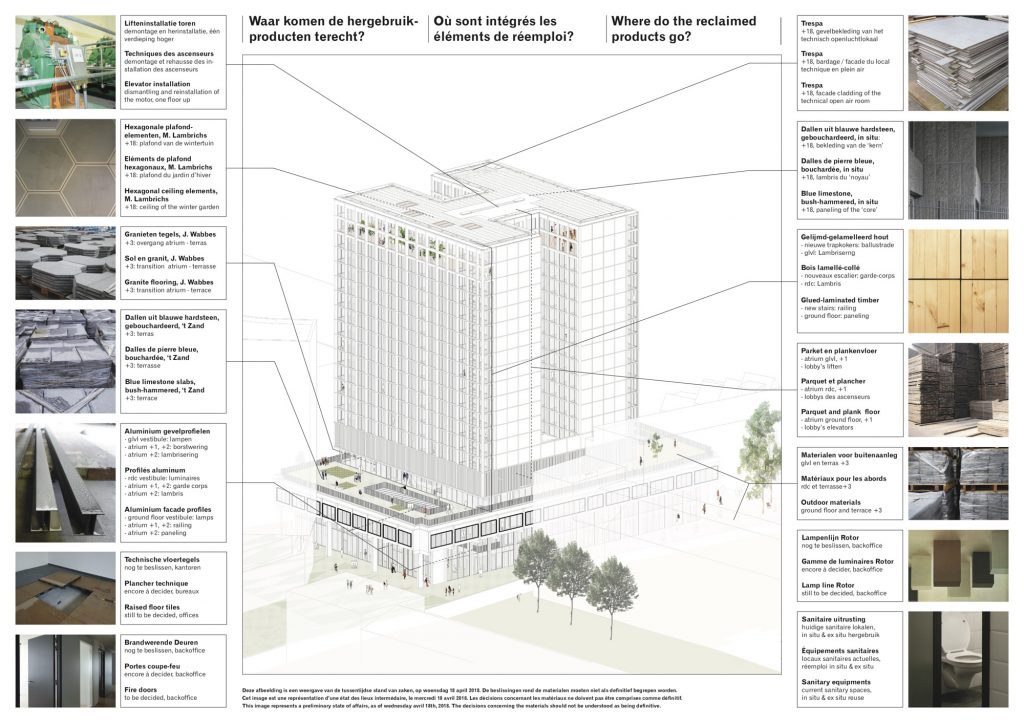

For the five months of October 2019 to February 2020, a careful deconstruction process was taking place on Brussels’s mammoth Brouckère Tower. Its façade of blue limestone was carefully removed, slab by slab, to be reused on its interior and exterior renovations. Two-hundred-and-eighty square metres, making up 140 tonnes of stone, mined locally and placed on the building in the 1960s, was recovered in this intricate process.

This delicate salvage operation was coordinated by Belgian company Rotor, a cooperative design practice that assesses and facilitates design decisions that integrate reuse, showing an alternative to deconstruction and demolition by promoting the careful dismantling of industrial parts, construction materials and other useful elements.

Through its more than 35 current collaborations, Rotor is shifting perceptions of how buildings are torn down and reassessing the manner in which they rise, taking a critical look at things happening in the industry in the name of sustainability and challenging notions of “new” being better. By reusing bricks, steel, tiles, doors and even handles and ventilation units, it works to have these installed in constructions or renovations that lie within 100 metres of their deconstruction site, calling for a lighter footprint that discourages imports.

Rotor’s approach to the built and natural environment casts a holistic lens over the industry as it explores the birth and afterlife of buildings, and considers that which is extracted from the earth in the process. Besides projects in architecture and interior design, the organisation produces exhibitions, books, economic models and policy proposals, taking both future generations and nature into consideration.

Believing in materials and bringing them back to life

In 2018, Rotor founding member Maarten Gielen noted: “Architects sift through everything that is, and everything that could be. Proposals of what to keep, what to amplify, what to invent, what to enact, what to glorify or what to erase are the essence of the practice. While the choice for marble cladding might help express a certain pretension of luxury or sophistication of a hotel, that choice also justifies the existence of a quarry and certain landscape alterations. The design has thus two spatial outcomes at the same time. An addition of material in an urban context, and a subtraction of material in its economic hinterland. Why is the one considered more ‘architectural’ than the other? Isn’t the architect ordering both of them with the same gesture?”

With such sentiments in mind, Rotor points decision-makers in the direction of better-employed resources. It encourages the support of skilled labour rather than the extraction and production of new materials, and evaluates how projects can lessen the impact of manufacturing and decrease the burden of waste materials that would normally be discarded in rivers and fields. At the same time, it contemplates manpower and the economy of jobs in deconstruction, cleaning and preparation, and respectfully engages with the cultural value of architecture and materials and the meaning they have in the world.

Rotor’s collaborative model is an innovative way to progress through the very controlled environment in which architects, designers and builders work. It presents an opportunity to create a new dialogue with old matter – like the 140 tonnes of blue limestone extracted from the earth in the 60s. By being treated and re-instated on the Brouckère Tower, these slabs remain part of the living Belgian memory of past and future generations.

Images courtesy of Rotor.