Why Tschumi Matters

In architecture, there is a fear of “theory.” Ever since the end of the Critical Project in the 1990s, many in the discipline have backed away from directly engaging with social and political thought. Maybe this change in direction was the product of the engagement with the then-nascent virtual explorations of space that took place twenty years ago. Maybe this retreat from engaging with obtuse ideas outside of architecture’s purview is endemic of the “blissful” 1990s where some proclaimed that “history” was finished and that dialogues with social life no longer had political consequences. However, the bliss of the Third Way of the 1990s is long over. With political, economic and social conditions rapidly changing, one has to wonder how architecture – arguably the most public of the arts – will adapt. We should ask ourselves how far the formalism manifested by computers can take us in terms of the discipline’s reconciliation with our current historical situation. Architecture may find itself at a juncture where theory – dense and prosaic as it may be – could help establish disciplinary relevance amongst a diverse populace in uncertain times. The works of Bernard Tschumi matter more now than ever. Didactic in his practice and precise in his execution, Tschumi offers architecture a means of synthesising practice and theory with reality. He does so not in order to flex intellectual muscle, but to demonstrate that the built environment can play an active role at a time when history’s future is more uncertain than ever before.

Architecture has always been problematic because of its inability to address issues in a timely manner. It is the nature of the discipline. The reality is that many years often pass between the birth of the initial idea, its design, its construction and the eventual occupation of the space. As a result, it is hard for a design to maintain any level of currency vis-à-vis its ability to engage with contemporary environments. In an art form as style-driven as architecture, aesthetics exist in a temporal limbo. While fashion and graphic design are able to respond to changing ideas and tastes with great speed, architecture is often unable to react quickly. It is left to either anticipate and establish future trends or else find that is outdated and irrelevant upon completion. Tschumi’s works show us that another way is possible. Architecture can be mutable insofar as it can create an environment that instantly responds to what is happening at a particular moment. This mutability allows for those who interact with these spaces, in other words the agents of the “now,” to define their present-day identity.

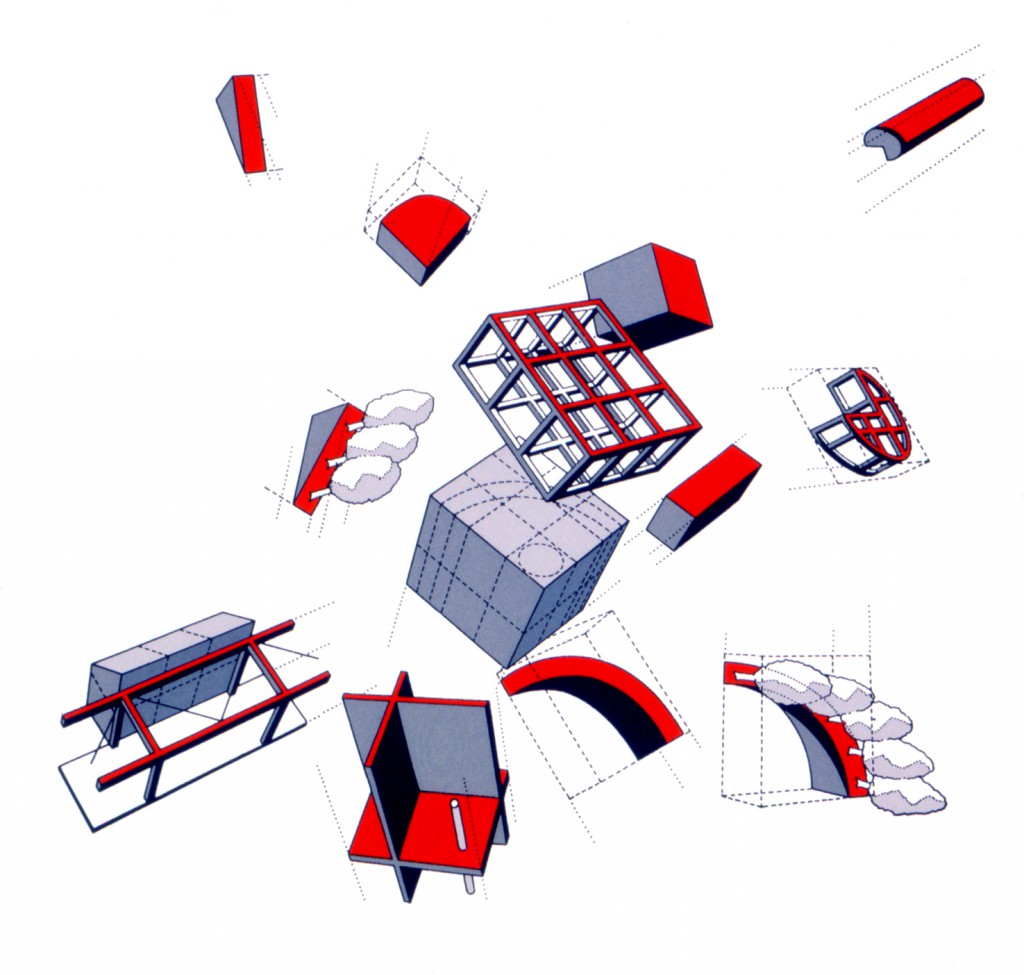

The Parc de la Villette, a former abattoir from the time of Napoleon III, is located in northeastern Paris in the city’s 19th arrondissement. The la Villette commission helped to solidify Tschumi’s presence in the canon of architectural history. His work there was the result of a competition to reimagine the site. It has since become the proverbial bread and butter of university architectural theory courses and much has been written about it. The project consists of a didactic, flowing landscape punctuated by 35 precisely placed red follies. It is endemic of the ideas of the late 1970s and early 1980s that abounded during the period when it was completed. However, these ideas, notably the mutability of language and understanding, have allowed for a project that is able to grow and live in the present moment. In his essay, “Abstract Mediation and Strategy,” Tschumi writes, “La Villette looks out in new social and historical circumstances: a dispersed and differentiated reality that marks an end to the utopia of unity.” It is a place where that which has not been choreographed can happen.

Because it is a design that operates through a set of complex operations, la Villette resists being situated within a particular architectural lineage. According to Tschumi, the design’s resistance to easy classification within a precise genealogy allows it to be defined by the people who populate it at that specific moment. While Tschumi is responsible for designing la Villette’s environment, it is more apt to think of him as having set in motion the mechanism that is the park. Be it the follies or the abundant greenery, the “architecture” appears when people interact with the space in infinitely unpredictable ways. Every person who comes to the Parc de la Villette, whether in the 1980s, 2016 or 2116, will have a different and unique way of interfacing with the site. Each of these approaches to understanding the space is unique and is shaped by an endless cast of figures, events, ideas and places, among other things. As a result, la Villette will always be current. It could be argued that this work from the 1980s is more recent than certain structures completed in 2016. It is more recent because its programmatic identities, which Tschumi wisely chose not to author, are in a constant state of reinvention. In contrast, architecture that heavily prescribes its uses and imposes a strict aesthetic interpretation will forever be tied to a specific moment and will resist any sort of transformation.

Because architecture takes so long to come to fruition, it behoves it to be flexible. It is advantageous for a design to not be fixed to a certain moment in time. This allows the design to not only engage with the environment around it for a longer period but also, more importantly, to invite people to engage and interact with it while defining it. To some extent, this idealism naturally comes up against the reality of the architect as author. The discipline, like other learned professions, prides itself on guarded knowledge and expertise. Architects do not dedicate years of their lives to study and practice only to have their work altered by an anonymous public. Nevertheless, it is true that architecture as a profession, like medicine or law, has ethical standards. In comparison with its peer professions, architecture is far less defined and outlined. Yet many in architecture believe the profession has an obligation to do work that benefits and enriches the public. By no means does this mean that design should be sacrificed in any capacity. Rather, the relationships between authors, subjects and objects should be reconsidered in a more totalising light.

We are now in a period where once-silenced voices are able to reshape the narrative of Modernism’s didacticism. Practitioners in architecture should be aware of the ways in which different people might and likely will interact with a designed space. Tschumi sets a salient precedent for this way of thinking. By creating a critical distance from the Modernist orthodoxies that prescribe the relationship between the viewer and the built environment, architects can help to create architecture that can engage and interact with an epoch that is increasingly difficult to define and illustrate. If the conceptual identity and even the physical operations of a built environment are plastic, then that environment will be able to respond instantaneously to a global environment that is in constant flux.

The Parc de la Villette serves as a model for creating anticipatory architecture that can be appropriated by anyone who engages with the space. This appropriation allows for anyone to develop their own understanding of the park and furthermore, to act upon that understanding. For architecture to have currency in the future, it must be ready to take on this role.