Wim Delvoye: Art in the Making

A conversation with MUDAM director Enrico Lunghi, who curated the institution’s vast retrospective on the unclassifiable Wim Delvoye

MUDAM celebrated its tenth anniversary with a vast retrospective dedicated to Wim Delvoye. The singular, unclassifiable Belgian artist has created a veritable world of Walt Disney —whose initials he shares— that swings between the sacred and the profane, the noble and the squalid, object and process.

In 2006 Enrico Lunghi, museum director and curator of the exhibition, convinced MUDAM to commission a chapel at the museum by the “Flemish master.” Ten years later, Chapel is still the site of artistic pilgrimages, proof of the artist’s position and status for an entire generation as it reflects on important questions: What does it mean to be ancient versus contemporary? What is the relationship between the fine arts and the decorative arts? How does seduction relate to dissonance?

TLmag talks with Enrico Lunghi, whose long, meaningful friendship with Delvoye reveals a shared sense of altruism.

“I wanted to show work by Wim Delvoye other than his Cloaca pieces and his tattooed pigs. His factory in China has actually closed and there are only about 40 of his pigs still circulating in private and museum collections. This themed exhibition does an excellent job of showing Delvoye’s work over time and its coherence. Though the art forms he uses may vary, he always asks fundamental questions.”

While viewers focus more on the values behind his pieces than on the pieces themselves, Delvoye’s artistic approach is evident throughout. He possesses a flawless mastery of numerous kinds of craftwork. “His works reflect the world in which we live, with its everyday objects, such as football goals and ironing boards. He reinterprets them in a way that is both idiosyncratic and logical. He adorns ordinary, commonplace objects with precious ornaments. By using manual processes and the decorative arts, he transcends the identity of objects in order to make them into something noble. This is true of his wooden and ceramic sculptures and his tyres. They allow us to see these objects in a different way with their full visual, conceptual and artistic added value.”

Unpacking Society and Systems

Delvoye also calls into question the way that our society functions. One excellent example is his gas canisters. “Millions of gas canisters are delivered throughout the world. He raises them up to the level of artwork by painting them with lavish designs inspired by Dutch earthenware from 17th century Delft. In doing so, Delvoye isn’t simply trying to distort the canisters. This intentional act sheds light on the whole symbolisation of the system. The same goes for his circular saw blades, which he decorates as though they were collector plates and then arranges in expensive dressers or other pieces of furniture.” Delvoye pushes us to think about systems of objects, those objects’ use and the way that society manages and oftentimes wastes them. “Super Cloaca” (2007), which greets you as you enter MUDAM, raises the issue of how to avoid waste. By pushing the concept to the extreme, he makes art out of waste so that we can better understand it and ask the right questions. He applies this same logic to the tractor tyres that he sculpts into rubber works of art.”

This temporary exhibition will surely go down in history. Walking through the rooms of the exhibition, the clear common thread is the art of transforming ordinary objects into noble objects. There are also the obvious exceptions of the Maserati, which is the luxury car par excellence, and the engraved shotguns, which evoke themes of masculinity. There is also a nod to the famous moped, displayed in a red felt case like a musical instrument.

Art History in Perspective

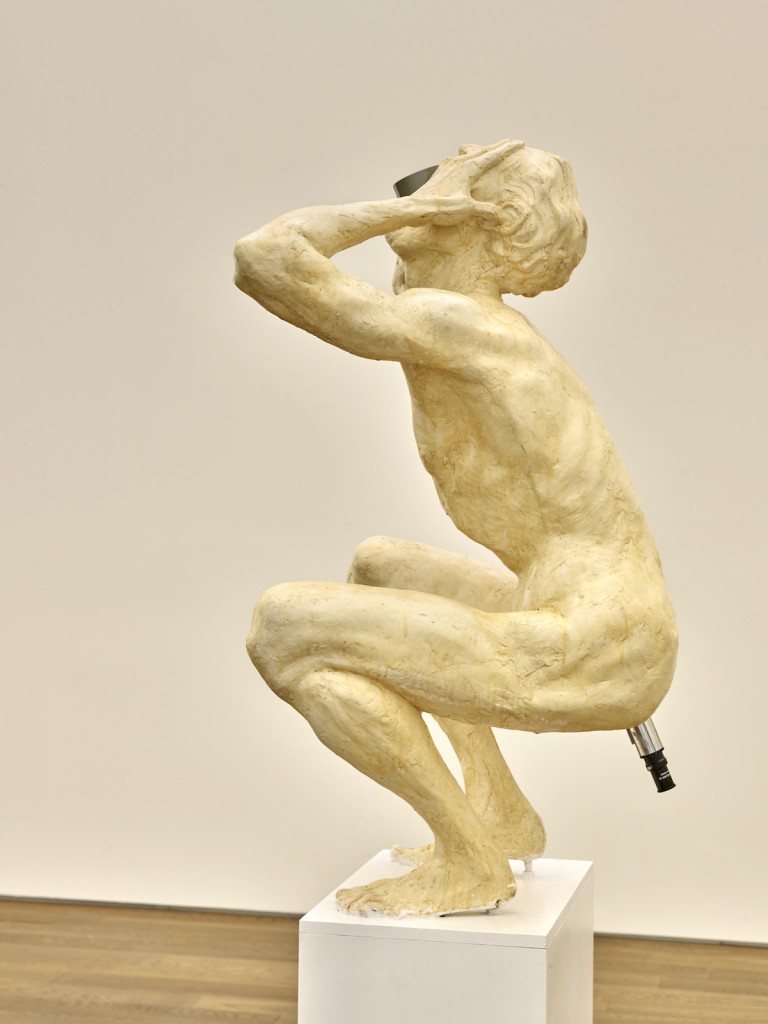

It was surely Delvoye’s upbringing in a devout Flemish community in Ghent that led to the artist’s fascination with art history and its Catholic undertones. “In his eyes, Christianity made it possible for the decorative arts to develop. You can see this in his crucifixes, which are anamorphoses of the crucifixes that preside over churches. The same can be said of his sparkling 19th century style sculptures and his earthenware discus throwers, which are made by the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory. While Delvoye’s ornamentation is polished, refined and full of references, his subjects are idiosyncratic. They invite viewers to see the work from a different point of view and bring new life to narratives. For example, his metal concrete mixer is an idealised model in the spirit of the bourgeois salons. It evokes certain clichés about the art history of the former Low Countries.” By referencing the Low Countries, Delvoye references the history of Flanders, Europe and Europe’s colonial past. Lunghi adds, “We are seeing reverse colonisation throughout the world today. In the past, artists sent their sculptors to the colonies. Today’s artisans are elsewhere. Delvoye is searching for superior kinds of savoir-faire. He blends patterns and ornaments drawn from western culture with elements taken from Indonesia and other faraway countries.”

Artist, Artisan, Entrepreneur

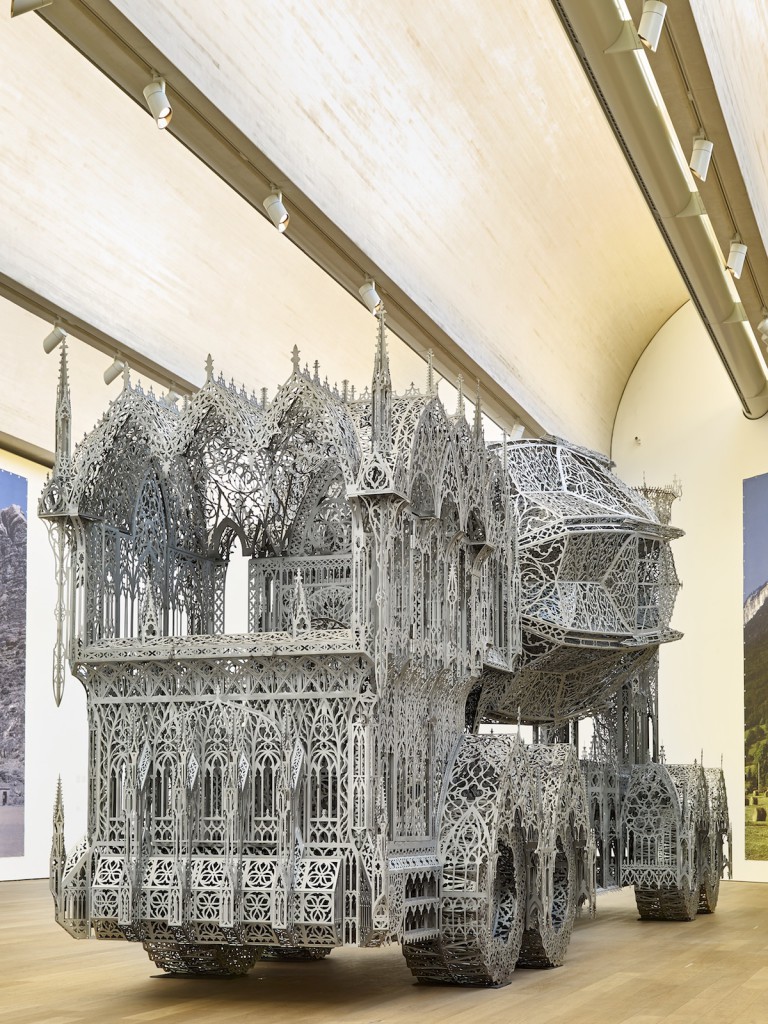

In Vitraux, in vitro et in vivo, the seminal text that Michel Onfray wrote for the Eldorado exhibition in 2006, Onfray describes Wim Delvoye as an artist who makes oxymorons. Lunghi takes another view, saying, “What strikes me about him is his ability to turn the ordinary into something noble. Suddenly, invisible objects become a familiar presence. Crucifixes are subjected to new rules, like the double helix of DNA.” Delvoye creates strong contrasts that reveal his deep knowledge and intuitive sense of the BioArt movement. In her exhibition catalogue essay, the young researcher Sofia Eliza Bouratsis describes how Delvoye’s art of distorting his subjects is counterbalanced by his exceptional mastery of “a vast range of incredibly sophisticated artistic techniques: canister varnishing, enamel painting, wooden sculpture, laser-cutting with steel, stained glass, photography, x-rays, drawing, various kinds of imaging and advertising design. He reinterprets both Walt Disney and the works of classical sculptors.” Delvoye’s fascinating poetics are in a class of their own. Rare is the artist who does not feel humbled by Delvoye’s multicultural, multidisciplinary talents. His gothic concrete mixer is without a doubt the ultimate symbol of the current-day human condition and of our globalised society, a society in which we are losing our identity.

There are few spaces or cultural phenomena that Delvoye has not explored yet. Lunghi notes, “The big room on the first floor of MUDAM displays Delvoye’s work etching ephemeral messages into giant mountainsides, inscribing them there for eternity. Alongside this site-specific installation are the big, gothic concrete mixer, which is a response to the neo-gothic Chapel, the Maserati 450s and the Rimowa-emulating suitcases, which are engraved in Iran and China. It’s truly a trip around the world.” After the exhibition, Delvoye may leave one of his trucks on deposit in the museum park. He is also working on a secular cemetery with a gothic cathedral in Luxembourg.

As for the exhibition, it is now on display at Museum Tinguely in Basel. The exhibition there focuses on the dialogue between Delvoye and Tinguely’s “useless” machines, whose sole purpose is to raise our awareness regarding vital issues by physically producing disenchantment and reenchantment. The underlying subtext of their work is childhood, topped with a hint of cosmopolitan, and in Delvoye’s case Belgian, surrealism.

The exhibition will be at the Museum Tinguely through January 1, 2018