Alex Schweder: Performance Architecture

Modifying the everyday, even just slightly, can have surprising effects. For reformed architect-turned-artist Alex Schweder, reexamining the mundane through strategic experimentation reveals how buildings perform and how humans genuinely interact with interiors. With an installation- and intervention-based practice, he explores this central question from various angles, for example looking at how constraints imposed by architecture force inhabitants to adopt alternative patterns and how the fluidity of built surroundings makes them reconsider their own routines, identities and relationships as well as their interactions with time and each other. Schweder touches on larger questions of society, commerce, culture, politics and the environment but modestly, does not claim to be a visionary. Still, the artist channels his design aptitude into the creation of visually and viscerally bold archetypical structures, which acts as an effective means of communication that invites the viewer in. A New York native educated at Pratt, Princeton and Cambridge, Schweder has developed work for venues including Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, The Glass House, London Design Festival, Scope Art Fair, SFMOMA, MoMA, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Manhattan Mini Storage and numerous galleries. Currently, he also teaches sustainability through performance at Pratt and interior renovation at Parsons School of Design. TLmag spoke with Schweder about his reflective approach and various projects that represent his artistic range.

TLmag: In exploring the function of collaboration, you’ve created installations with artist Ward Shelley that enact the idea of tension but also demand interpersonal balance. How do such projects come about?

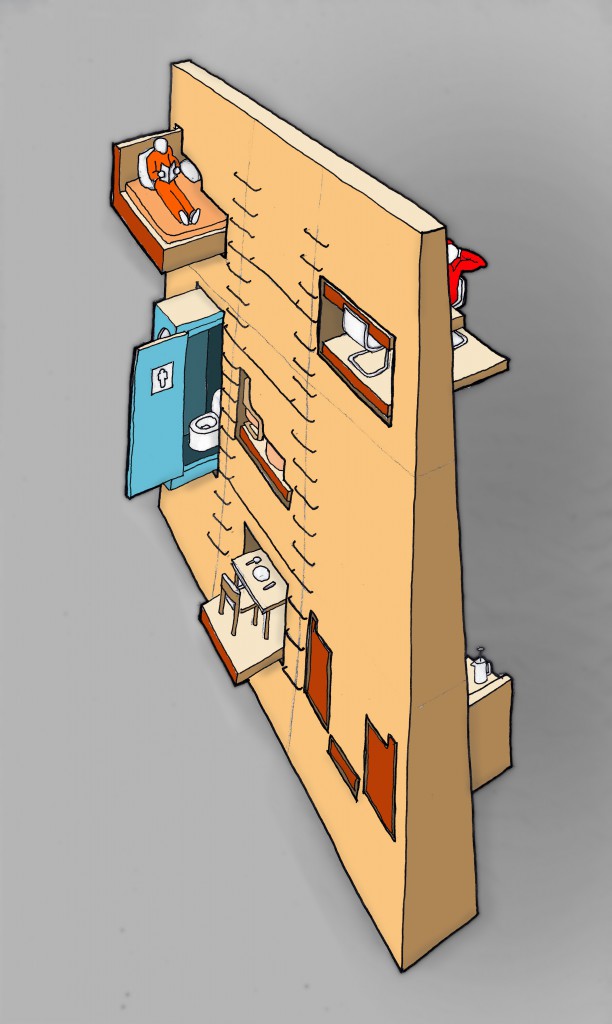

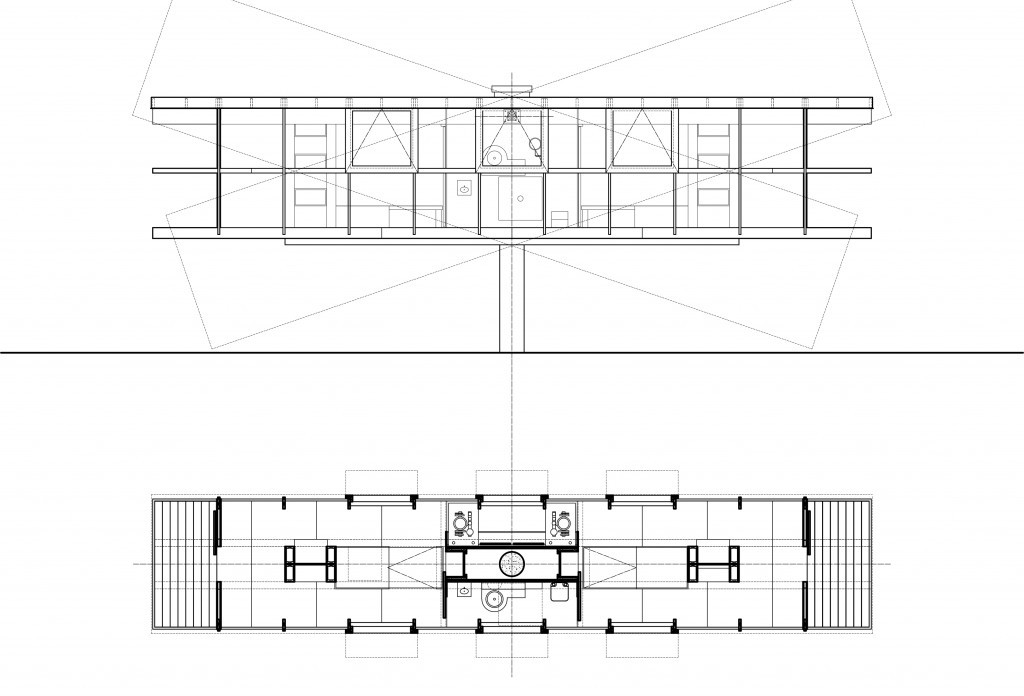

Alex Schweder: We develop our conceptual propositions first and determine logistical issues later on. It is only through living the experiences that we understand what these projects mean to us. Such an approach differentiates what we do from publicity stunts. Still, there are sensationalist aspects to living in a wheel. [In Orbit was a 2013 project in which Schweder and Shelley lived on the interior and exterior of a circular installation for 10 days.] It becomes much more about taking care of each other and balancing power dynamics when you consider the precariousness of living on a continuous curve. What I did inside had a strong impact on Shelley’s condition. In projects like Counterweight [where two performers live in a tall shelving unit and share the same tethered rope], or ReActor [a 2016 installation comprised of a house pivoting on a single pillar, where two performers needed to achieve a physical balance], there was more equity. These performances were scripted to reflect the banality of everyday life. Presenting this idea within the extreme context of our installations, a contrast emerges. It’s about changing one factor in the standard formula. There’s no fourth wall, which allows us to have open conversations with visitors. However, we try to answer their basic questions—like where we go to the bathroom—through visually explicit elements to facilitate a deeper discourse. This fall, we will be mounting Your Turn at the Aldrich Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Inspired by Terry Gilliam’s dystopian film Brazil, the installation will feature a space divided by a wall. Shelley and I will occupy either side but share one set of essential amenities and furniture. Though the concept is symbolic and relevant at the moment, this latest project shows that, for us, the world is better when people cooperate.

TLmag: Where do architecture and design come into play?

A.S.: My field of inquiry is architecture, but I approach it with an artistic methodology. We offer questions, not solutions. But it’s also important to note that the user has become central to architecture. Rationalism and the history of performance both support this approach to the field. Both explore similar questions about interaction. Take the Frankfurt Kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1926. It was a functionalist piece of design that prescribed a set of rules for efficient movement through a small space. Bernard Tschumi took formalism and transformed it into “programming,” a principle that could exist separately from the building in question. Furthermore, the user becomes central. In my practice, I explore how inhabitants participate in and interpret their spaces, how they employ architecture to enact their identities. You can look at an Ikea Survival Kit in quantitative terms, i.e. how many people will be able to use it. Or you can take the same object and examine it through an art-space framework and see how it raises larger questions about how we live. I see performance and architecture as intrinsically connected. It’s not about doing something radical, it’s about helping to change people’s perspectives on how things occur in the everyday.

TLmag: Talk about your Inflatables series.

A.S.: I create inflatable forms that condition space to evolve over time based on scripted sequences that oscillate to various sounds. The Sound and The Future (installed at Detroit’s Wasserman Projects in 2016) is one example. In this case, I wanted to pay homage to the city’s history and the origins of Techno music. In 2014, I mounted Wall to Wall Floor to Ceiling at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Every available space was filled with inflatable installations that changed how visitors experienced the venue at different times of the day. There are cues in architecture that tell us how to behave. A door handle’s shape provides you with instructions on how to use it. These understandings are partly cultural, but they also come from the way form can inherently direct certain interactions. Space is thought to be static, but what I try to do is layer it with time. Viewers who engage with these inflatable installations witness the formation of a window, room or doorway. The continual changes keep them on their toes, inspiring a sense of awareness about their relationship to architecture.

TLmag: How do your Performative Renovations push your approach a step further in reconsidering the social and user-centric aspects of finite space?

A.S.: Having worked as an architect in New York for eight years, I designed many high-end residential apartments. In hindsight, I realize that these spaces were frozen in time and could not reflect the changing identities of their inhabitants. With this in mind, I wanted to see how far I could push the idea of architectural performance. From a sustainable angle, I also wanted to explore how I could suggest the concept of renovation through a set of guiding instructions that would reorient how people use what’s already there, rather than gutting their kitchens and using new materials. It’s hard to deny that we map our stories onto our stuff. It’s a way of writing who we’ve been and who we want to be. This project began with one-on-one conversations I had with people about their interiors at both a Berlin gallery and a space provided to me by Manhattan Mini Storage. Almost a form of psychology, conversations like these allow us to take tacit stories and verbalize them. With problems laid bare, it’s easier to rectify them. From these conversations and by identifying key issues, I developed performances based on the design principle of instruction. Dressing up like the client and reenacting an improved experience in their space, I afford them a level of detached reflection. They compose images of their apartments as a reminder of how they can solve their problems. As part of my PHD dissertation, I’ve enacted 60 of these interventions in mostly New York. Once I have the title of doctor, I hope to set up SOAP (Schweder Office of Performance Architecture) and use my studio near Times Square as a space for these conversations. I hope to develop this New York-based project even more in the future. In one case, I worked with a South Korean investment banker who had just bought a beautiful ‘perfect six’ apartment on Central Park West. It had just been renovated but something was still missing for him. The new space was too impersonal and didn’t feel like home. I asked him if there were any moments in the day or physical elements in the apartment that alleviated that feeling. He told me the kitchen contained some reminders of his family in Seoul. Together, we determined that he was home sick. There are no marble countertops you can order that will remind you of home. Like anxiety, this condition is associated with sociability. My intervention consisted of changing the time zone in one room 13-hours ahead, to match South Korean time. Now every time he feels homesick, he can go into the room, change into traditional clothing, eat a Korean meal and call his mother. The scenery reflects this atmosphere.

TLmag: How have things changed in New York. What does it mean to work in this city?

A.S.: I’ve lived in New York on and off for 46 years. I’ve gone away and returned multiple times. What I’ve been able to understand over the years, is that this city is the best place to grow. It’s a big enough place to become who you are within it. New York accommodates those of us who leave and come back; it accepts our changes. In truth, no one is stagnant. Like us, this city is in constant flux. Creatively, there are endless opportunities to collaborate that exist from just being here, in the proximity of major institutions and influential figures. In paraphrasing John Baldessari: if you’re at it long enough, you’re the only one left. A large part of being a New York artist is finding ways to sustain and adapt your practice beyond any of your contemporaries.