Axel Vervoordt: Accepting Things as They Are

In this interview, Co-editor and visual artist Amy Hilton meets and is led through the organically curated home of one of Belgian design’s most influential figures and collectors; Axel Vervoordt. Here, the two speak of their mutually shared interest and affinity towards stones, and the importance of ‘earth-centred’ design approaches.

From restoration to curation and design, Axel Vervoordt’s career has been guided by his intuition and his discerningly curious gaze over different genres and time periods. His art and antique expertise lend themselves to an organic approach, a fusion of elements from nature, in keeping with a respect of their existing environments. He creates serene, mediative atmospheres – often through dialogues between complementary opposites. By mixing subtle tones and hues with shadows, he draws out their power to reflect the dark sheen of materials like gold, embroidery, patinas or cloudy crystals. Less concerned with a continuous search for light and clarity, he seeks more subdued forms, of the natural and the time-worn, with a particular focus on what is oriental and ancient. Digging deeply into aesthetic and philosophical meanings, he assumes an all-encompassing silent power over what he does, exuding a sense of cosmic harmony.

Perhaps the most captivating moment of our exchange took place before the visit of his enchanting home at ’s-Gravenwezel, just outside of Antwerp – and even before he guided me through his exquisite art collection. While conversing outside on the patio, he carefully placed three smooth white stones on the table in front of us, between spots of light and shadows of overhanging vine leaves. It was an effortless yet elegant arrangement of these stones, which he told me he had found in Greece. This simple, understated gesture gave the stones a sudden, deeper meaning, underlining the vison that has suffused his work over the past half-century. For Axel Vervoordt, these three white stones were as precious as a Brancusi.

TLmag: Stones possess something ultimate, something that will never perish. They have an intrinsic, infallible and immediate beauty. They help me find a sense of balance. We seem to share a mutual interest and affinity to stones.

Axel Vervoordt (AV): I am fascinated by them too. These three are so beautiful, I could admire them for such a long time. In the park over there, I have a collection of huge stones I found in a granite quarry in East Germany. They are part of the origin of the world. The first time my horse saw them, he felt their presence. He was afraid of them. I feel like stones themselves are like living animals. Even after millions of years of existence they are still alive; they just live very, very slowly. They have that patience.

TLmag: Patience is such a fundamental virtue, particularly in light of current events. We are undergoing a radical state of change and uncertainty, demanding a major re-evaluation of our values in respect to our relationship with the Earth itself.

AV: I think that the value of Earth is greater than ever now, even with the global pandemic. We humans used to think that we were the rulers of the Earth, but now we realise that it is Earth ruling us. And this is something that we have to accept: we are servants of the Earth, not at all its rulers. We have to treat Earth as something so precious and so essential to our being.

TLmag: What you describe aligns itself with the current paradigm shift towards a deeper ecological, more holistic, unified way of thinking. It is becoming essential now that we maintain more of a ‘non-anthropocentric’ viewpoint, that is to say, more of an ‘earth-centred’ approach, not putting ourselves as humans above or outside of nature.

AV: Indeed. As humans, we are part of the Earth. If we don’t respect it, it’s auto-destruction. And this is what we see is happening. However, I do think that when one thing goes extremely negatively in a society, another thing goes positively as well. Because things are going so badly, there are a lot of people thinking very positively and wanting to do something to generate or foster change.

TLmag: Yes. There is a sense of equilibrium in that idea. It is time that the ‘yang’ now retreats in favour of the ‘yin’. How should we move forward?

AV: I think it’s important to be open to all kinds of influences. Not rationalistic or dogmatic. Not thinking that we know; but knowing that we don’t know. You can never make the same square in a circle, though you can attempt it. I want to be a free person, and make the best of every moment. I want to be open to people who have new ideas.

TLmag: The animistic belief system in Japan known as Shinto posits the sacredness of all phenomena without hierarchy, including stones. The ancient Chinese considered that insight could be obtained from the strange shape or pattern in a rock or a veined or perforated stone.

AV: On the side of my swimming pool in the garden here I keep a small collection of 13 stones that I’ve brought from all over the world. I have given every stone a name, as each one represents something different. Every day I arrange a new composition with them. I start with Earth or Heaven or Intuition, Wisdom, Intelligence. The heart-shaped one I tend to leave placed in the middle.

TLmag: And to think there are some among us who just ignore them, viewing them as such mundane objects. Personally, I have always favoured the gnarly ones, the broken ones. The diamonds with the flaws. Which leads me to that Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi, a guiding principle in your work.

AV: Yes, wabi is the beauty of imperfection. Accepting things as they are. It advocates simplicity and humility. There are parts of Japan where they admire two apples that are exactly the same, but that’s not necessarily the type of Japan I am attracted to. I love the Japan of beautiful pottery where the humans are part of its creation, not the totality of it. A sort of ‘in-between creator’. The artist makes the pottery, he gives it to the fire, and the fire transforms it. Part of the final creation is left to nature to complete.

TLmag: Art that comes into being in an interstitial space between phenomena. Recognising nature as an active creative agent.

AV: Yes, there is such beauty in the interaction with nature. And more, when there is an artist who is humble enough to realise that it is not just him who made it. I admire how the Japanese have a lot of respect for everything. Even the paint itself. And this is what impressed me so much especially in my discovery of the Gutai movement. It is not about the subject of what would be painted necessarily, but it is the paint as a material itself that they have the most respect for.

TLmag: When did you cross that bridge to the East? And was there anyone significant who inspired you or had any impact upon this path?

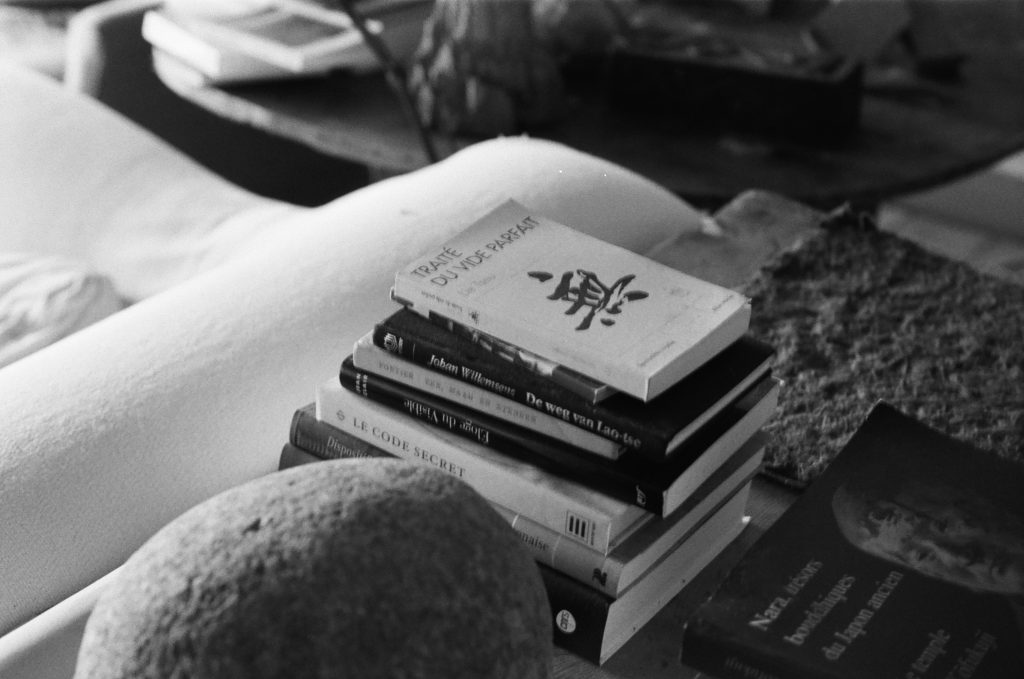

AV: I became a collector at a very early age, and an art dealer when I was only 21 years old. From the beginning, I always loved old, non-restored pieces. I always had a taste for great simplicity. At around the age of 22-23, I bought a little street of houses to restore in Antwerp and I met some fantastic people – artists, philosophers and collectors. I knew a particular collector at the time, a neurologist, Dr. Jos Macken, who, as well as having a strong interest in contemporary art, had a special collection of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy and pottery; it was at this moment that I was initially introduced to Zen philosophy. Furthermore, it was this man who introduced me to my artist friend, Jef Verheyen. Jef and I subsequently became very close friends. I learned so much from him; he brought me the sense of the ‘void’ in art. He taught me about sacred geometry. He gave me my first book on the Golden Section.

Tlmag: Your vision is not dissimilar to that of an artist. I witnessed that for the very first time in Venice, where you presented one of your series of six major exhibitions at the Palazzo Fortuny between 2007 and 2017. I was completely immersed in the powerful dialogues you had conceived between art and philosophy.

AV: The series of exhibitions during the Venice Biennale’s were very major events in my life. Each exhibition took two years to finalize. We took the first year to prepare the theme. I organised think-tanks to understand the meaning behind each exhibition – Artempo, In-finitum, TRA, Proportio and Intuition. And only in the second year did we start to make a choice of the artworks to be exhibited. The last one was Intuition, and we knew that it would be the last. With regards to the dialogues, I have always liked to mix very valuable things with very humble, basic things. I always want to look at art like a child who doesn’t know its value – just purely to feel and love things as they are. Like placing a rusted piece of iron next to an Andy Warhol. Or just as if I placed ones of these stones next to a synclastic sculpture.

This article was originally published in TLmag34: Precious, A Geology of Being.