A Disappearing Act II at Galerie Party

For the second part of their kid-friendly exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, GGSV’s Gaëlle Gabillet and Stéphane Villard recruited an unlikely partner: silent protester Liu Bolin

For their latest design project, a “gallery” for the youngest museumgoers of the Centre Pompidou, Studio GGSV’s Gaëlle Gabillet and Stéphane Villard worked with two ruthless consultants: their eight-year-old and three-year-old children —their youngest, not yet one, couldn’t articulate any opinions on the amorphous objects they were testing for the exhibition.

“Sometimes we’d show them pieces that we thought would interest them, and [the eldest] would say: ‘That’s horrible, it frightens me!’”, explains Stéphane. But they did figure out a pattern during the prototype phase: “They always liked the weirdest, strangest ones. Children are curious by nature.” As they quickly realised, the Under-10 audience was more demanding and exacting than they had foreseen.

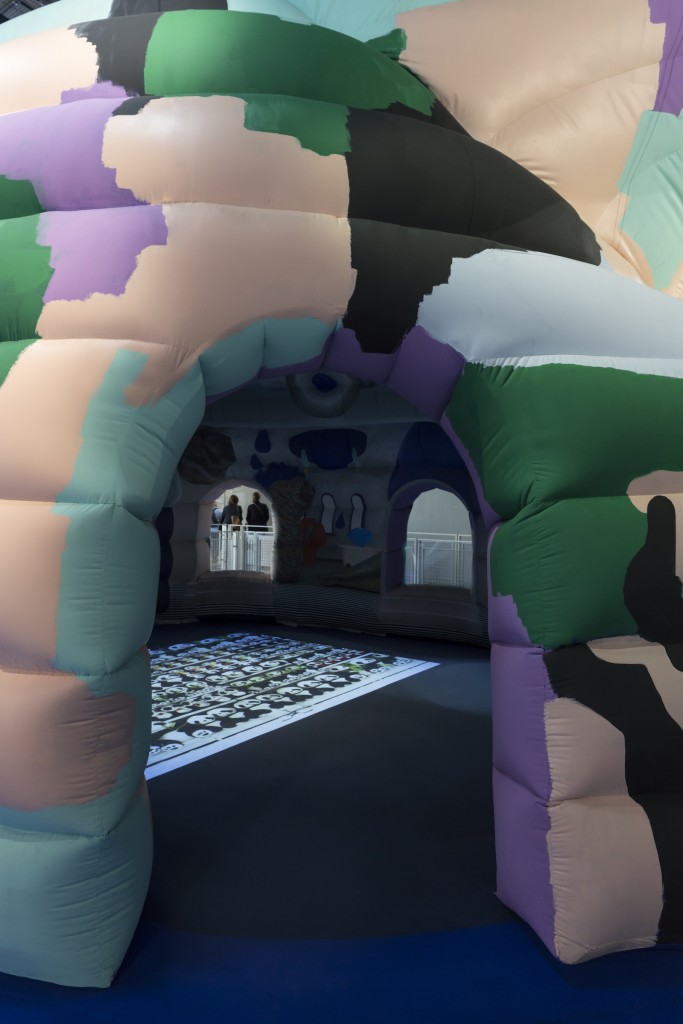

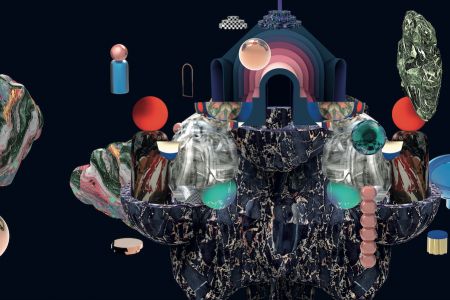

But that was for Act I of Galerie Party, the much praised exhibition they arranged for a commission to celebrate the Pompidou’s 40th anniversary. The objects inside, with references to the likes of Sottsass, Pesce, Miró, Magritte and LeWitt, came from the timeline of the art centre itself. To explain this to small visitors, the duo used the story of two little creatures, Gellaé and Séphante, who lived in a cavern under what is now the Pompidou. Once one of Renzo Piano’s blue pipes reached their abode, the couple decided to follow its path and explore the new building, where they saw “humans doing strange things, looking at big colourful images,” according to Villard. The “Galeroom” replicates, in their style, their favourite artworks from those daily observations throughout four decades —including an inflatable homage to Piano and Rogers’ landmark structure.

For Act II, which opened in early September, the creatures’ human namesakes enlisted Chinese artist Liu Bolin to create a disappearing performance. Bolin, known as The Invisible Man for his chameleon-like performances, camouflages himself through clever use of paint and photo angles in thought-provoking urban landscapes as a form of protest. When Gaëlle and Stéphane do design for adults, part of their work is focused on pollution and the conscious use of waste materials, so they were very interested in working with Bolin to include this social thread in the Galerie —another part of their work is their production of colourful scenography, which is why they were picked by the Pompidou for this project in the first place. But there was another, more emotional reason behind their partnership with Bolin. “There’s always something magical that comes from this effect of disappearance,” explains Stéphane. “Children can feel it. It’s close to what they think: sometimes they are here but they don’t want to be here.”

Faithful to the referential style of Gellaé and Séphante, for the Liu-inspired Act II children can now find aprons that play off the patterns found on the floor and the large objects in the Galerie. If they place themselves in just the right spot, the mimetic effect allows them to blend with the background and become almost invisible. The artist himself visited the spot in early September to enact a similar performance in the vicinity of the gigantic, wooden birthday cake located in the center of the space.

And what did the most experienced of their consultants think of this apron-based proposal? “At first, he said ‘c’est nul’,” remembers Gaëlle, laughing at the memory of their critical eight-year-old. “But then he started to play with the prototypes, and he said ‘not bad… not bad’.”

Small visitors have indeed responded effusively to these installations. In Act I, children as young as two would put together dining rooms and cars with the spare pieces; others would make up silly games with the floor projection of Gellaé’s object-producing magical fountain. “We thought it would be a moment for meditation, where children would sit and look at the objects appearing in the fountain, and in fact, it was a crazy game for them,” Gaëlle says, amazed. “They tried to catch the shapes. They would scream ‘It’s coming!’ and run after them” —a scene that Stéphane describes as crazy as “a Berlin nightclub, with people dancing early in the morning, but for children.” In Act II, the designers were delighted to see that the costumes didn’t register as gender-specific —boys didn’t see them as a “girl” thing, and they were instead very excited to play dress-up. “It just surpassed our expectations,” she adds. “Even the mediators, who are there every day to help the children in case they need it, were astonished to discover new things every day. They found their happiness contagious.”

But the adult visitors were also fond of the Party. Some have thanked the duo for giving them a place to connect with their children in their own worlds. Others have giddily seized the opportunity to behave like their younger selves, first dipping their toes in the water by helping their offspring with the pieces and then surrendering to the playfulness of it all. “It’s like the toy train on Christmas Day: in the end, it’s the dad that plays with it, not the kid,” laughs Stéphane, kneeling on the Galerie’s carpet floor to impersonate some of the “No, Daddy will do it!” parents. Others, with no child in tow, would sheepishly take a peek at the colourful, dream-like space and ask: “What is this? Can I go in without children?”

It’s a sign of the times. For a recent project with the Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Gabillet and Villard went over an archive of 50 years of production and saw that art in the last decade, with crashed, burnt and black themes, had mainly screamed against our current fears: war, environmental crisis, genetic modifications. But now Memphis, with its critically lighthearted nature, is all the rage —just turn to the most recent example of its influence, the London Design Festival’s playful Villa Walala. “We took from [Memphis] because we think it’s good,” added Stéphane. “We have to prolong it, to make it live again.”

But the GGSV team had yet another aim. The main intention of Galerie Party is, indeed, to provide children an environment that is complex enough to entice them —“children, as young as they are, have complex questions”— but lax enough that it allows them to express themselves by playing “a game where they cannot fail.” But below the surface, the object was to start nourishing the first layers of something quite… well, French: an artistic heritage. It’s a birthday party, for sure: there’s an anniversary, a giant cake, an inflatable castle, costumes, games and a present. “The idea is that art is a culture you can learn, but also a heritage that belongs to them, and that you can transform in your own way,” explains Stéphane. The hope is that these shapes, based on the works of some of the best and brightest in the art world, will somehow be absorbed by their sponge-like minds and remain in their subconscious, to emerge later as a visual vocabulary and historical references to better understand the world as adults.

On display on the east-facing wall of the Galerie, next to the entrance, are both Bolin’s scrap-made installation (see the cover image) and the suit he used to disguise himself in it. Stéphane and Gaëlle worked together with him in Biarritz, clipping together the waste material as quickly as possible to fit the painter’s schedule before their photo deadline. Once they zoomed out and looked at their joint creation, to their own surprise they realised that, unintended, it looked a lot like the map of the United States, from sea to shining sea, even with a hanging Florida in the lower right corner. That was around the time of Trump’s ascent. The subconscious does act in strange ways.

Act II of Galerie Party is open until January 8, 2018. Act III, with the collaboration of French artist Morgane Tschiember, opens on January 20.