Mounir Fatmi: Experimental Archives

Mounir Fatmi has always been curious about the transformation of objects and how, with a slight change of context or position, they can take on entirely new meanings. Now, he regularly goes back into the archive, transforming materials into a highly charged body of work.

TLmag: What does the phrase, “archaeology of materials” mean to you? How does it relate to your work and your vision on materials that you are interested in using in your artwork?

Mounir Fatmi (MF): The first things that come to mind when I think of the word archaeology are the field work, the digging, the dust. I was fortunate to live across from the museum of archaeology in Rabat, Morocco. It was a great pleasure for me to see over and over again all the prehistoric and pre-Islamic artefacts. The utensils found at the Sala-Chellah site. The sight of these end-of-life objects often reminded me of the flea market in the Casa Barata quarter of Tangier, where I was born. I also passed my childhood there playing among the mountains of antenna cables, televisions, radios and electronics. I understood later that these objects had had a life, a time of glory, and that they then fell into disuse, became obsolete and were finally stranded in my neighbourhood. They created within me a deep reflection on technology and its use. They also compelled me to take a critical position towards the history of the technologies and their influence on popular culture.

TLmag: When we think of archaeology we generally first think of ancient burial sites, stones, or pots. But in a sense, with the speed of technology we are seeing materials become “artefacts” in our own lifetimes: VHS cassettes, Super-8 Cameras, 8-tracks, typewriters. There is a nostalgia for these objects, but they are relics of a time gone by. What is your perspective on this?

MF: I personally don’t have a sense of nostalgia towards these obsolete objects. The starting point for all of my works is more critical. It is true that the development of technology has been moving very fast these past years, and that we find ourselves with all these technological objects on our hands, without knowing what to do with them. We passed very quickly from the era of the typewriter to analogue images, to digital, and now we are already speaking about post-digital. This issue of speed, which is one of the characteristics of our modern culture, compelled me to also search within religious books, like an archaeologist trying to understand the past. We can’t forget that the first book printed by machine was the bible. I think this is the first time in our history that we find ourselves in this situation where there are so many ‘undead’ media. We can look in the past for artefacts and at the same time experience this obsessive desire to archive everything. We archive practically everything we produce, and thanks to new media, we record nearly every moment of our lives. We can describe this as the archaeology of new media, television, cinema, internet. In the future, this archaeology will no doubt be carried out in “information clouds”, and archaeologists will be like young children who are gifted in computer languages. We need to see the media of today as the fossils of tomorrow.

TLmag: You’ve talked about how in the future, even 30-40 years from now, people will see the materials/artefacts in your work before the actual artwork itself? What do you mean by that?

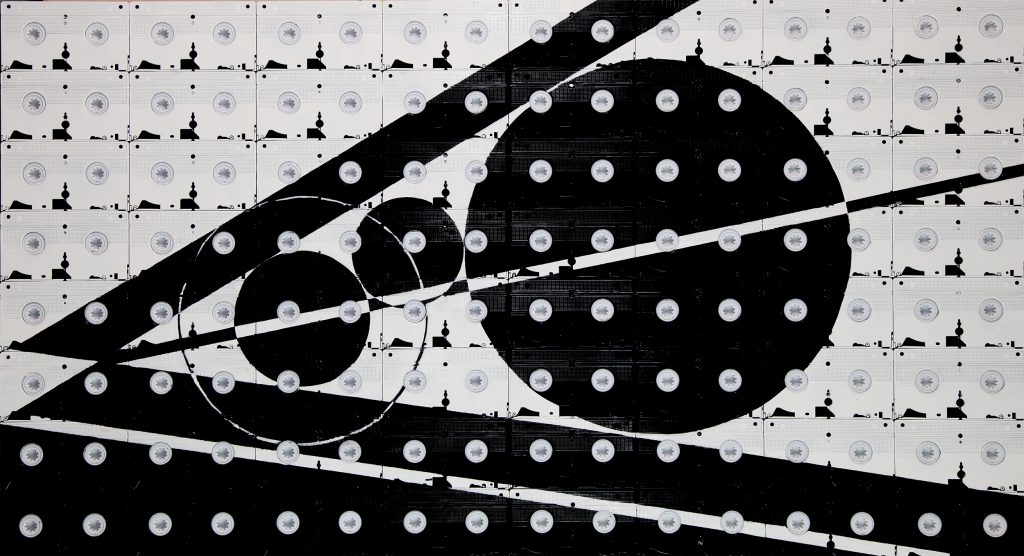

MF: I know that my works will be seen differently in the near future: because they associate the design materials and the design itself. I work more or less with what American sci-fi author Bruce Sterling called in the 1990s “Dead Media”. My installations propose an artistic concept and at the same time they archive the materials and the media for future generations. It’s a type of archaeology that converges cultural media fossils, such as television antenna cables, VHS cassettes, photocopiers, religious books, but also dead languages and video games. We mustn’t forget that everything “old” had a moment when it was “new”. In fact, I can never get that idea out of my head. When faced with an artefact of the past, I always try to imagine it at the time when it was a functional object. It is true that we live in a period of great acceleration, and new media and objects quickly become old. What is interesting is to also find this new concept of “vintage”, which makes old objects new again. So we find ourselves with the old in the new, and the new already old. We finally moved from Marcel Duchamp’s Ready Made to Ready Dead. So to answer your question, yes, in 30 or 40 years, my works will also be seen as pieces of archaeology archiving the media and materials of the past.

TLmag: The French philosopher, Michel Foucault, has been an important inspiration to you. How has his work connected with you as an artist?

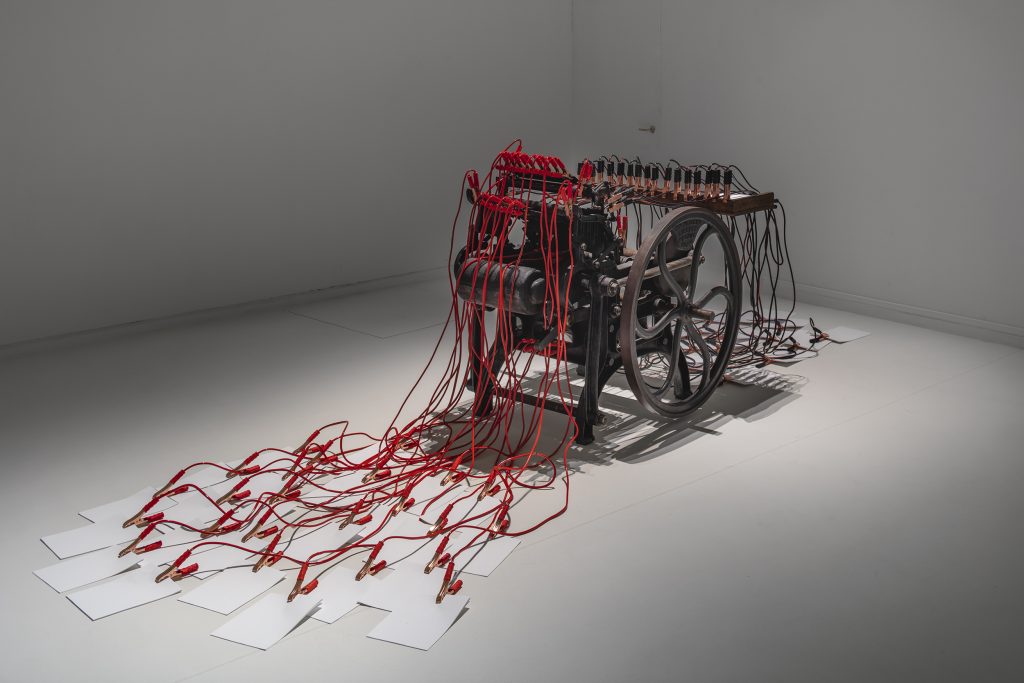

MF: I’m very happy that you bring up Michel Foucault. My artistic research has been influenced by many philosophers and anthropologists, and Michel Foucault certainly has a good spot on the podium. In his book “The Archaeology of Knowledge”, he described archaeology as a dangerous word. He developed a theory of the essence of history and historicity by contrasting them with his own “archaeological method” as a new, universal way to describe the history of ideas. If we see history as the domain of archives, then archaeology is intended to analyse it. Michel Foucault’s lectures were a great help to me during the creation of the “ Sortir de l’histoire” installation, where I used the archives of the Black Panthers and especially the FBI’s wiretapping documents, to which most of the members were subject. I believe that it is essential for an artist to survey the field of archiving like that of archaeology; for me, they are very closely linked and are complementary. I certainly don’t search for truth in these documents. I know there is no absolute truth, except in the dogmatic, as Foucault says. What interests me in using the archives or the archaeological artefacts is again the history of ideas and their transformations. 20 years ago, “PC” meant (in French) “Parti communiste”, today it means “Personal Computer”. Charles de Gaulle and John Fitzgerald Kennedy were once presidents; today they are also airports. To start, Picasso was only an artist, now it is also a car. This evolution of concepts functions for me as a barometer, as clues to understanding the rapid transformation of our modern society.

TLmag: The installation you recently made in Japan for the Echigo Tsumari Art Triennale, titled, Casabarata, is a house filled with working chimneys. It almost looks like a future ruin or a comment on the environment. Can you tell us about this piece?

MF: With the installation Casabarata, I explored the relationships between memory and architecture, between past and present, conscious and unconscious. In my artistic work, memory, or rather forgetfulness, is something that keeps coming back to haunt me. I had to dig deep within myself, to detect the true from the false memories I have of my childhood home, in order to design the project for this installation. Casabarataacts as the ruins of my own memory, as a hybrid place, holding the imaginary and the real. Both reassuring for its allusion to the family home, and dangerous for its open, unprotected aspect. Behind the beautiful façade, the third dimension of the installation enables the discovery of a house in chaos. It starts with missing windows, a narrower-than-usual front door, a non-existent roof and many chimneys that desperately attempt to warm the cold home that is completely open to the outside. I especially wanted to offer a retrospective reading reminiscent of a screen memory, the deconstruction of this same memory, and the recomposition of another memory.