Ola-Dele Kuku – Architecture as Critique

TLmag spoke to the conceptual architect Ola-Dele Kuku about his unique approach and two key projects.

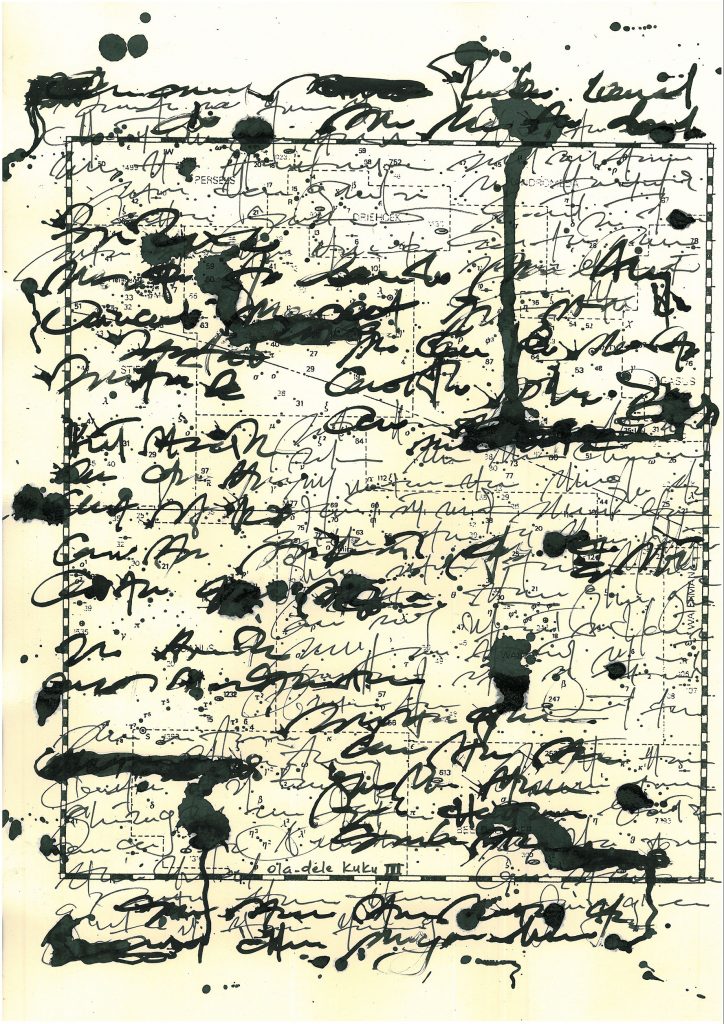

Nigerian born, Brussels based architect Ola-Dele Kuku has translated his architecture training into a conceptual art practice. His ongoing projects stem from deep philosophical inquiries into the current state of culture, identity, and geography. Having studied at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-ARC) and later in Italy, Kuku has received numerous accolades including the Grand Prize – Prime Minister’s Prize’ Award – IFI Nagoya International Design Competition and the ‘License of Honour’ Tech-Art Prize Award from the Vlaamse Ingenieurs kamer. His instigation-based installations have been shown in exhibitions around the world, including the 15th Venice Architectural Biennale.

TLmag: How are you able to channel your background in architecture while formulating conceptual works that address the social and philosophic issues of culture, perception, identity and dissemination?

Ola-Dele Kuku: The greatest human achievement is the discovery of numbers; anchoring the abstractions of the universe through representation and objective distinction. I’m interested in how thought becomes reality, in scale. However, perception is often measured, in one’s own mind, based on previous sensory experiences. An image arouses far more than visual response and deals with one’s attitude, impression, and audible experience. Such foregone conclusions form a bias that impedes our understanding of space and time. We need clocks to guide us. Drawings and imaginative thinking help us rectify these dimensional disconnections. As an architect, I’m drawn to the composition of structure; which is defined by both tangible and intangible force. Any creative endeavour begins with the consideration of reason; both in terms of function and a subsequent thought process. It is paramount that applied architecture, design application, and the creative arts today are adopted as adaptive tools to address the recurring epidemic of conflict and post-conflict rehabilitation; as what drives the evolution of our culture.

TLmag: In what ways does an ongoing project like Opera Domestica project combine furniture design and architecture to express meaning?

O.D.K.: We live according to past definitions of repetitive domestic ritual, as reflected in different areas of our homes: the living, bathroom, bed, dining and cooking rooms. Yet, these spaces no longer represent the specificity of our day to day. Today, architecture is detached from human experience. Our activities are no longer rooted in particular spaces. Instead, objects themselves are the determinant factor, which render the organization of space redundant and out-of-touch with changing socio-cultural conditions. My intension was to challenge this standard, Opera Domestica is a personal archive; an architectural object that stores and disseminates information. The project was instigated by my fascination in Medieval automatons; da Vinci’s inventions. The first iteration of the project, entitled Teatro dell’Archivio was inspired by Capitano Agostino Ramelli’s Book Wheel concept from his book, Le diverse et artificiose machine del Capitano Agostino Ramelli, published in 1588. My reinterpretation comprises different key elements: outer wheel as the information unit is divided into 12 segments as to denote the 12 months and zodiac signs of the year. It not only rotates vertically but also revolved horizontally. Inside, a second assimilating unit opens up as a reading table. The dynamic object is intended to communicate the value of knowledge and wisdom.

TLmag: The Diminished Capacity installation you developed for the 15th Biennale Architettura di Venezia (2016) posed the question “Africa is not a Country.” What problematics were you highlighting?

O.D.K.: There is a common misconception that comes with the use of the word Africa. There are currently 54 sovereign countries, nine territories and two de facto independent states that make up this continent. Hence, Africa is not a country. This habitual representation paves over the individual achievements and potential of each nation. Semiotically, the words London and Paris elicit the image of the Big Ben and the Eiffel Tower, respectively; both are symbols of intellectual expression, people’s achievements and potential. This in turn illustrates a synthesis of people-environment interrelationship and interdependence. Perception of the environment by the individual is manifested by means of subjective analytic translation of experiences and endeavour which in turn reflects a behavioural response and attitude towards that environment. The word ‘Cotonou’ or Accra or Lagos and the names of other major African cities still need to be acquainted to symbolic images of reference and identity. The conclusive product of intellectual expression and creativity lies in Architecture, Art, Design and Literature. This is also what is referred to as culture and inevitably, becomes a dynamic quality of collective participation within any social system.