Kaspar Hamacher in the Trees

Giovanna Massoni writes about the work of Kaspar Hamacher for the A/W 2021 issue of TLmag36: All Is Landscape. Hamacher currently has a selection of his sculptures on view at Spazio Nobile Gallery through January 16, 2022.

Being asked to write about Kaspar Hamacher puts me in a rather difficult position. It doesn’t happen often that trying to find the right words gives me a feeling of artificiality, a sense of inappropriateness. Because his pieces – which are simulacra of doing – need to be experienced. His work evokes and reveals worlds made up of wind, earth, water and fire. Useful or useless, works of art or functional objects, they are hard to describe because they have been carved, burned, chiselled, to fit in with an interstitial space between nature and culture. And this shape-shifting place belongs to nobody, because it is part of a whole that is for everybody.

Explaining Kaspar reminds me of the story of Italo Calvino’s story of The Baron in the Trees, a teenager who decided to live in a tree, up high, free, surrounded by nature. Cosimo does not withdraw from the world. He doesn’t become a hermit. He loves, he cultivates his friendships, he takes part in life at a distance that helps him understand, that gives him a clearer perspective of nature and the lives of others.

“Everything happened as though the more he decided to remain hidden in his branches, the more he felt he needed to create new relationships with the human race”.

Designer, artisan, sculptor. Nature and being, life, force and noises, smells and the landscape are so present that nothing can reduce them to a single language. What syntax can be used to compose an account that can convey the life, the dimension of the experience of this unique fusion between intuition, sentiment and physical strength? What idiom can be communicated, without making use of categories, which would be pointless here? Function, abstraction, pragmatism and a profound spirituality, all of these definitions in which we put our trust to create an acceptable narrative never seem to fully fit with Kaspar’s approach. The questions he is asked strive to put him into context, establish a theory about him, and even to slot him into a segment that is not truly his, or which does not totally fit him.

Kaspar is Kaspar. But far from being a self-referential character, he opens up his approach to confrontation and to the advice of others, of friends, of colleagues. His laid-back dimension, his “natural state”, makes him impervious and impartial to any theoretical construction in favour of a more intuitive and empathetic approach with the material and the natural dimension of his profoundly “terrestrial” being (1). And it is around this broad freedom and this simple attitude that he invites us to pull up a chair and take part in an intimate meeting with his world without any prejudice or points of reference.

THE ROOTS

When you meet people with such deep roots in where they are from, few are as capable of making it understandable and so universal. He was born in Eupen, on the edge of the High Fens, just a few kilometres away from Aachen (DE), Maastricht (NL) and Liège, in the south of Belgium, which suits him perfectly. Forests as far as the eye can see, a prestigious artisan heritage, the immense riches of a cross-border culture. Kaspar has lived and worked in nature since he was a child with his family. He learned to understand it and listen to it, taught by his father, a forest ranger. Growing up among trees, knowing how to look after them and respect their life cycle is a heritage that he has decided to perpetuate and pass on. For him, working with wood became the most direct way of protecting and adding value to this natural resource.

He was inevitably seduced by the art of the great sculptors, and Michelangelo and Constantin Brâncuși in particular. Two artists who revealed material by show- casing its natural purity. The non-finito, the unfinished aesthetic of the Renaissance genius, who asserted that the form is already present in a block of marble, in nature, in clouds; or the material power of the Endless Column by the Romanian artist who wrote: “It is the very texture of the material that stipulates the theme and the form that must come out of the substance, they are not imposed by anything external”.2

“At the beginning, I wanted to become a sculptor but the colleges that I went to didn’t have that as an option. So, you could say that I am a bit of an autodidact.” An aspiring sculptor, a trained carpenter, a graduate in product design. Explaining Kaspar’s training by focusing on his academic career would move us away from his main goal: creative freedom. However, the different stages and experiences that have marked his journey have fed into a personal endeavour with a constant balance between artistic drive and working environment. During his studies, this open conflict with the academic precepts of mass production and industrial materials found a sense of relief that would turn out to be a crucial step in Kaspar’s career: his experience as an apprentice, in the workshop of Casimir Reynders, finally helped him hone his understanding of solid wood, opening up new prospects for his approach. Wood can be “sculpted”, combining the designer’s perspective with exceptional craftsmanship. Without any compromises.

It was at that moment that I met Kaspar. Chequita Nahar, director of ABK (Academie Beeldende Kunsten in Maastricht), had asked me to work with design students on their final year projects. When I saw Das Brett – the control, the balance: nothing was superfluous or meaningless – this silent, majestic object that could coherently communicate with the brilliant simplicity of Der Lederriemen, I immediately stopped thinking of Kaspar as a slightly confused student whose hand I needed to hold and I allowed myself to be guided…

THE BRANCHES

Despite his aspirations and how difficult he found it to adapt to a restrictive discipline, the work that he built on during his studies announced his official arrival in the design world. His pieces stand out right away: in an environment that is packed with industrial prototypes, his furniture-sculptures make a statement about the courage of unique objects that have been created out of authenticity and real savoir-faire.

Kaspar’s work radiates more than most. The warmth of the wood is profoundly human, and probably conveys one of the main virtues of his œuvre: it speaks to others and brings together what others feel. This empathy, this tension be- tween the inside and outside worlds, like branches that help the leaves absorb the sunlight that they need for photosynthesis and to produce oxygen, is a circular system.

The energy of his approach is a constant exchange with others. It offers itself generously, and at the same time comes from a network of friends and colleagues, suppliers, collectors and gallery owners, or quite simply the public. The role played by those around him has created a durable constellation, based on trust and friendship. “The thing that motivated me the most is the people around me: they encouraged me, they helped me learn techniques or make choices. First of all you, Giovanna, and definitely Casimir, Bram Boo, Alain Gilles, then Damien Gernay, Norayr Khachatryan, and friends Fabian von Sprenkelten, Valentin Löllmann, John Franzen, Matylda Krzykowski, and Lise Coirier and Spazio Nobile Gallery.” The many exhibitions and the prizes he has won since his early days have definitely helped to consolidate his intent to persevere and uphold his own values and the way he works over time.

The solo exhibition that the CID Grand-Hornu dedicated to him was a real challenge: telling his story through the pieces he has created over the course of a decade and demonstrating his determination to pursue his work, in an endless quest for forms that create a dialogue driven by the intuition between mankind and nature. “For me, the exhibition at the CID Grand-Hornu represented a very important point, it is the summit, and it is a challenge to carry on. I have evolved every year, and this exhibition offers me the chance to show the different stages I have been through side by side. From pieces that were more functional in the beginning, to those that are more metaphorical and artistic.”

Kaspar Hamacher’s work is convincing. His work appears in collective and personal exhibitions, at international design events, in museums and in galleries (starting with Stefan de Jaeger’s Box Galerie in 2010 and carrying on today with Spazio Nobile in Brussels). His audience includes private customers, collectors, architects… This popularity, which has seen him receive a people’s choice award on at least two occasions (Dynamo Design Award in 2008 and the Henry van de Velde Label in 2012) reveals the consistent quality of his pieces: the essential language that expresses his craft, his respect for the material and his passion, without any conceptual or stylistic mediation. Kaspar is a kind of outsider who finds where he belongs in a crucial time when the debate about the Anthropocene, the dichotomy between culture and nature, sustainability, ecology and a return to frugality demand that the mass production of objects and ideas be called into question. And it has been his good fortune, I’m sure of it, that he has been exhibited in industrial contexts. His pieces, his functional sculptures have been and continue to have the power to assign artisan production its true value.

THE TRUNK

Kaspar is not an urban dweller. The reason why he gave up the idea of living in a town or city after a few years in Brussels once again reveals the essence of his work: “When I had the idea of using fire to hollow out pieces of trunk and create the legs for my stools, I realised that it was impossible to do that in a town. I needed open spaces. So, I returned to Eupen.”

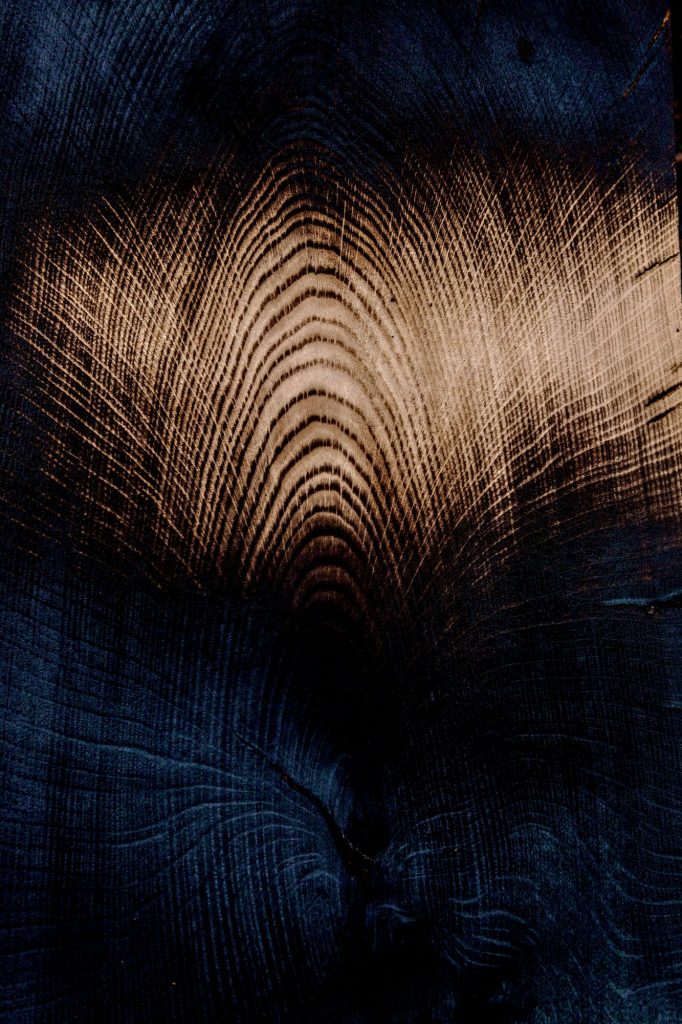

His work’s seductive power does not lie in the object or the material itself, but in the traces of his métier, which are always visible. Like a topographical survey of gestures, techniques and tools, these objects reveal the performance, the physical and mechanical efforts, like an intimate relationship with texture, volume and weight. The challenge of working with solid wood involves a series of ethical rules that need to be followed: nearby natural resources that have already had their lives taken away from them; the quality of the work, self discipline; the value of time; creative freedom. The hub is the workshop, but it is not an enclosed, solitary space; rather it is the heart of his work, where the most important branches converge. Exploring the forest, collecting dead trees, transport. His work is a never-ending, dynamic, ceremonial activity, where a well regulated production cycle, for the most part one that is self-sufficient, organises the process: long waits (the climate allowing him to go into the forest, or the time he needs to allow before he can start working the wood) are interwoven with cutting, burning, chiselling, all the while allowing his intuition and ideas to mature while he works.

Der Hocker, Der Lederriemen, Das Brett, Die Chaise- longue, Ausgebrannt, Der Stein, Der Baum… Kaspar Hamacher, cares as much about his freedom as he does about ours. The titles of his pieces are the names of things, of functions or of the technique used, always expressed in his mother tongue, German. The object is given to us directly, without any mediation. It is up to us to choose the level of abstraction, to decide whether or not to elevate it above the status of a piece of sculpture or to see it as a piece of furniture; or even to contemplate it in its essential simplicity, like a poetic fragment of nature.

“I have never constructed strategies, conceptual frameworks. For me, the concept is a feeling, people, the materials that I choose. Each individual sees different things in my work. That is what I love.”

You can see the routine, the technical repetition. The choice of simple functions (chairs, tables). The forms that are repeated but are never the same. The variations in scale take the object from the functional to the symbolic. Wood is never a medium but rather a substance. His ongoing commitment to mastering his technique drives him to constantly assess himself, in an ongoing process of self-study.

The material is cut, sheered, polished, chiselled, dissected, burned, to reveal its heart through touch, smell and the visual and emotional experience. All of these actions, which look violent and invasive, are never de- signed to exalt or transform nature, but are rather the results of an intelligence de la main (intelligence of the hand) that is capable of expressing a pure feeling of attachment to natural phenomena.

“It’s hard to make a tree trunk more beautiful than it already is. My ideas must always respect the boundaries between destruction and creation”.

THE HEART

“I love the heart of the tree, I find it really interesting to see the wood as a whole and not just the pieces.” The wood in the heart of the tree is a guarantee of authenticity and purity, but it is also a life message. Kaspar often talks about his pieces as metaphors. And you could say that the heart of the tree is the perfect metaphor for his approach.

His technical research always aims to achieve one main goal: to make sure he is able to express himself and create his pieces with complete freedom. That’s why not long ago, he would alternate between his work in the work- shop with collaborations involving carpentry or making stands. The money that he earned was always invested in machines and tools. “I am now living for my work. But it was hard before. Carpentry funded my freedom, my art.”

“I’m not short of ideas, but I am aware that I have not totally mastered my savoir-faire. That’s why I feel that it’s important and necessary to talk to people who have more experience and who can help me. There is always a technical solution. Break your borders – friends say to me, push your limits!” In fact, savoir-faire is never a series of notions, it’s actually about adapting to ideas, to physical and emotional conditions. It evolves, experiments, is assimilated.

“The reason why I started to make my burned stools is that I could make them myself. To empty out the trunk of a tree, I needed a lathe, and I didn’t have one. So, I decided to hollow out the wood using fire.”

Burning is one of the most remarkable techniques that he uses. But can it be regarded as just a technique? Or is the idea of burning more about the meaning expressed by the performance of the fire and how the material reacts, which determine and convey the content, the message, the metaphor? Or is it just an ingenious and profoundly natural process that creates a frugal alternative to a technical deficiency? Describing the work of a craftsman, Richard Sennett writes “an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake”.3 This attitude is probably the one most inherent in the approach taken by Kaspar and his workshop.

“My objects need to be touched, to be used. I don’t want to create icons.”

This phrase, which places Kaspar even more firmly in a hybrid, but resolutely creative, dimension, invites us to approach his work without filters, and to let it live. Kaspar’s pieces bring us closer to nature and liberate us. It’s serendipity.

*The Kaspar Hamacher quotes are taken from a conversation that I had with him in his workshop in Raeren on 14 January 2021

Footnotes:

(1). Musée du Centre Georges Pompidou. Dossiers pédagogiques-Collections du Musée 2010. <http:// mediation.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-brancusi/ENS-brancusi.htm>

(2). Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climate Regime, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2018, “Le Terrestre tient à la terre et aussi au sol mais il est aussi mondial, en ce sens qu’il ne cadre avec aucune frontière, qu’il déborde toutes les identités.”

(3). Richard Sennett,Ce que sait la main. La Culture de l’artisanat, Albin Michel, 2010

Kaspar Hamacher is currently exhibiting work at Spazio Nobile Gallery through January 16, 2022

This article appears in the A/W 2021 issue of TLmag36: All Is Landscape