Glissant As A Toolbox

On what would have been Édouard Glissant 92nd birthday, TLmag revisits Hans Ulrich Obrists’ insightful essay focusing on the influential Caribbean thinker and cultural commentator.

I believe a lot in rituals. I get up very early every morning, and I always start the day by reading 15 minutes of the Martinican poet, writer, and philosopher, Édouard Glissant. His work is like a daily toolbox, a means of understanding our world, but also a way of thinking through other possibilities for it. Across the world today we witness the homogenising forces of globalisation whereby local differences are negated in favour of dominant and at times dangerous worldviews. Moreover, the plurality of words, meanings and interpretations has increasingly become under threat from cultural colonisers who seek to quash the richness of our differences.

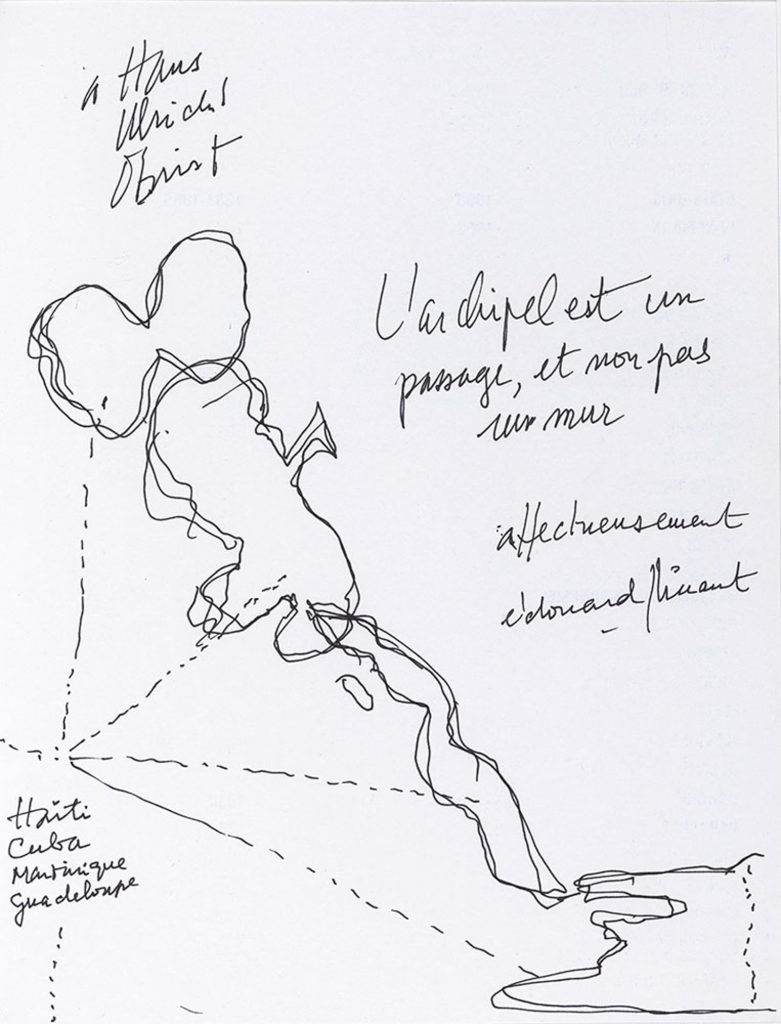

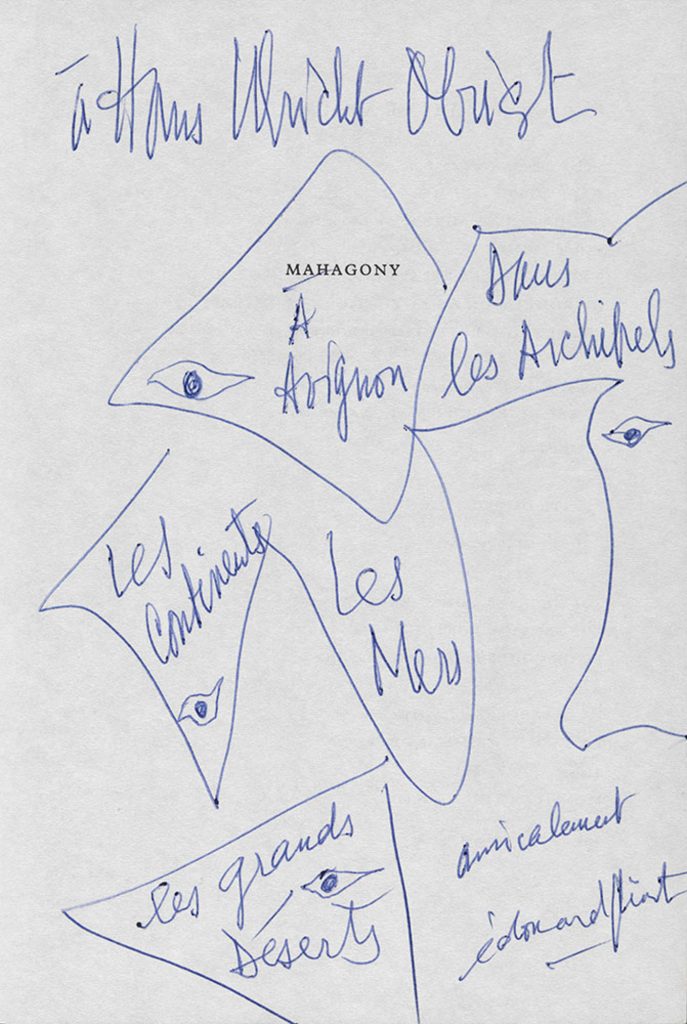

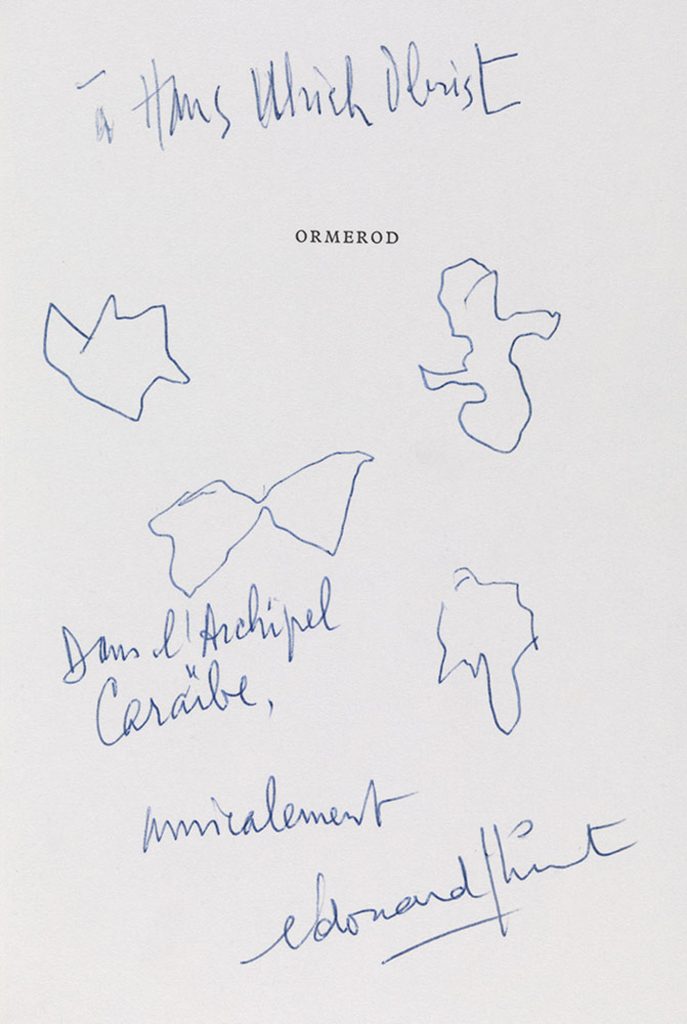

Glissant, who was born Martinique in 1928 and died in Paris on 3 February 2011, was one of the most important writers and philosophers of our time. He called attention to means of global exchange that do not homogenise culture but produce a difference from which new things can emerge. Islands of Creation is a particularly relevant term to Glissant’s work, as it is the very history and landscape of the Antilles that forms the departure point for his unique mode of thinking. For Glissant, what is so significant about the Antillean archipelagos is the fact that they are an island group that has no centre but consists of a string of different islands and cultures. Contrary to continental thought, which as we have witnessed with increasing alarm, leads to forms of nationalistic self-enclosure and self-determination, archipelagic thought endeavours to do justice to the world’s diversity. It permits difference whilst maintaining connection; it finds shared commonalities whilst preventing tactics of cultural exclusion. As Glissant says:

Continents reject mixings . . . [whereas] archipelagic thought makes it possible to say that neither each person’s identity nor the collective identity are fixed and established once and for all. I can change through exchange with the other, without losing or diluting my sense of self. And it is archipelagic thought that teaches us this.

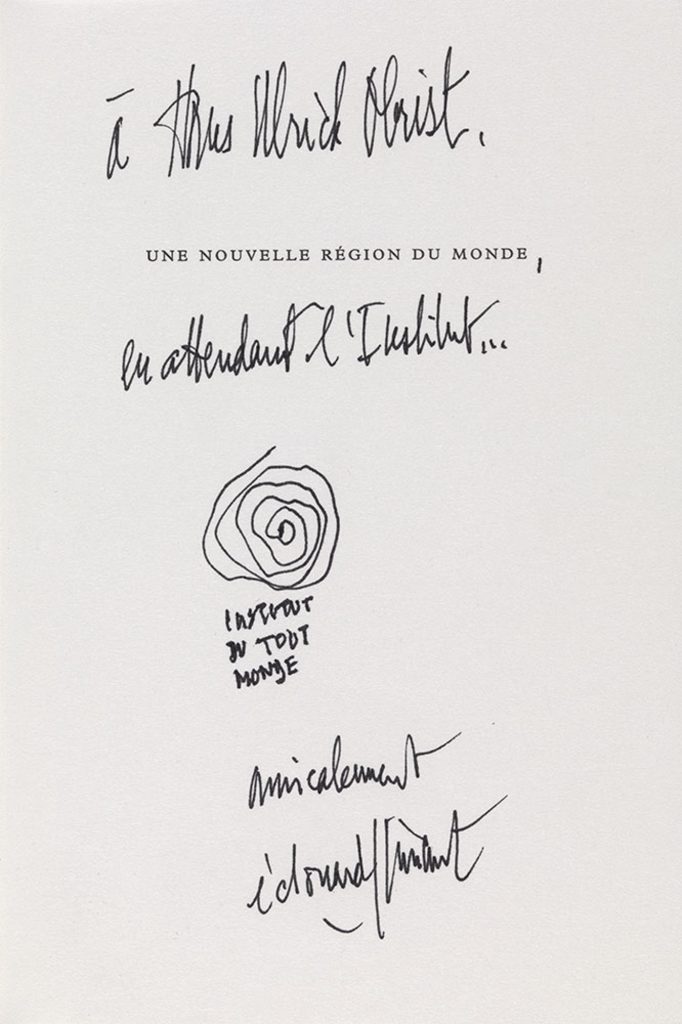

To counter the homogenising forces of globalisation, Glissant coined the term ‘globality’ (mondialité) for a form of worldwide exchange that recognises and preserves diversity and creolisation.

Glissant considered the blend of languages and cultures a decisive characteristic of Antillean identity. His native Creole was formed from a combination of the languages of the French colonial rulers and the African slaves; it contains elements of both, but is itself something independent and unexpectedly new. On the basis of these insights, he later observed that there are similar cultural fusions all over the world. In the 1980s, a period in which a theory around globalisation was developing, in essay collections such as Le Discours antillais (1981; English: Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays, 1989 and 1992), he expanded on the concept of creolisation, applying it to the worldwide process of continual fusion: ‘Creolisation is a process which never stop’.

Many of my exhibitions, such as ‘Cities on the Move’, which I curated with Hou Hanru, and ‘Do It’, a project that emerged from dialogue with Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier, have been based on the archipelagic ideas of Glissant. Particularly in the case of co-productions that toured worldwide, we wanted to create an oscillation between the exhibition and the venue. The exhibition changed places, but each place also changed the exhibition. There were continual ‘feedback effects’ between the local and the global. Similar things occurred in ‘Do It’, in which every location had its own instructions for the actions of local artists. What came to be called ‘globalisation’ has led to exhibitions traveling between continents. The question is how we can react to that circumstance in such a way as to produce differences rather than assimilation.

There is something defiantly utopic about Glissant’s term and worldview, which I believe is also very much rooted in the unique potential and value of art as a means to reconfigure reality as we know it. In the research for ‘Utopia Station’, which I curated with Molly Nesbit and Rirkrit Tiravanija at the Venice Biennale in 2003 and later in other venues, we conducted countless conversations with Glissant about this concept of utopia. He criticised the classical utopias, such as Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s island of Utopia, for being conceived as static systems. He designed a new, alternative form of utopia consisting of a continuous dialogue that used the archipelagic structure of connected islands as its starting point. It has always been my belief that artists are leading the way in proposing alternative realities. Through Glissant’s archipelagic thinking, together with the radical potential of artists to offer new ways of understanding our present reality, we can conceive a multiplicity of future possibilities.

This article was originally published in TLmag 31: Islands of Creation and is being reposted today on the occasion of Édouard Glissant’s birthday on September 21st (1928). Glissant passed away in France in February 2011.

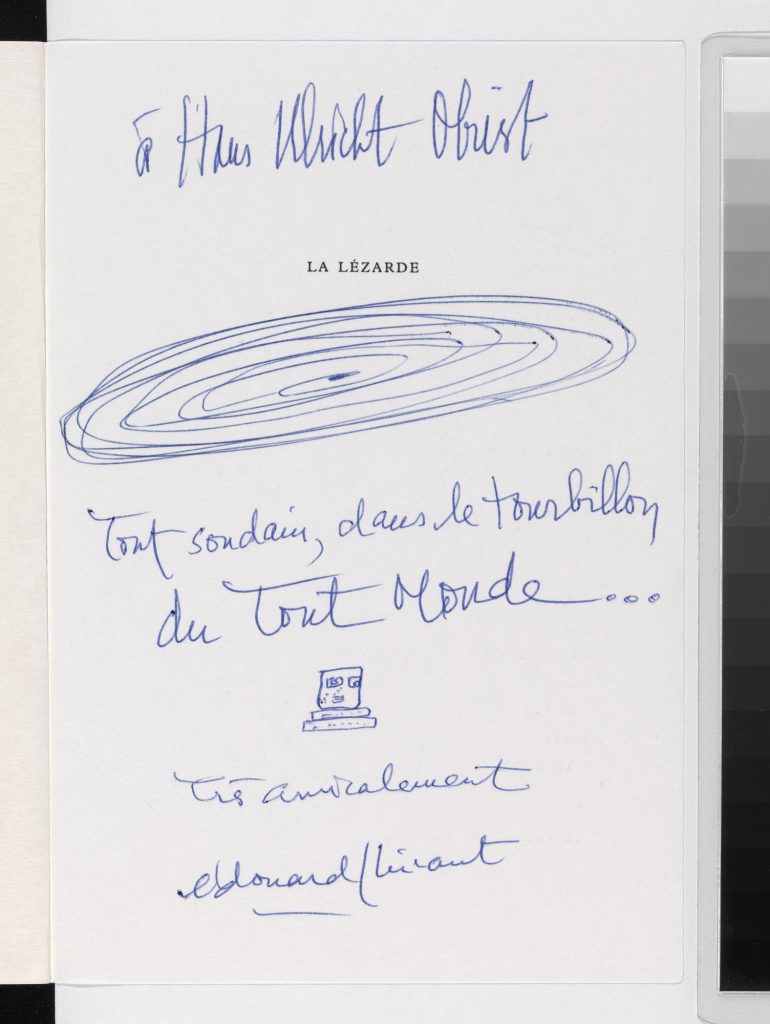

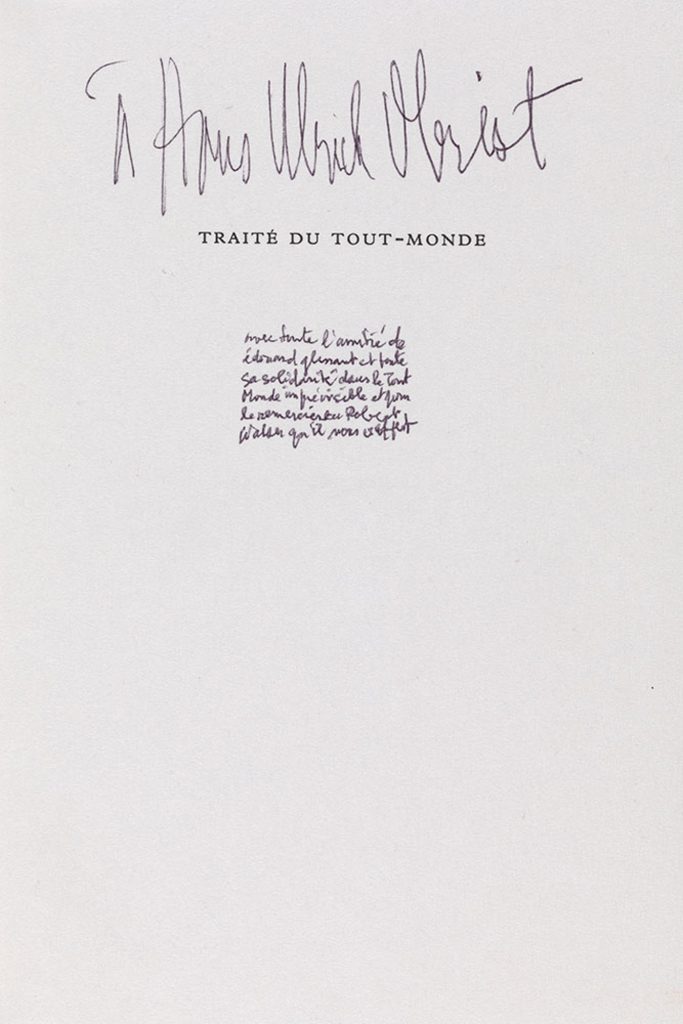

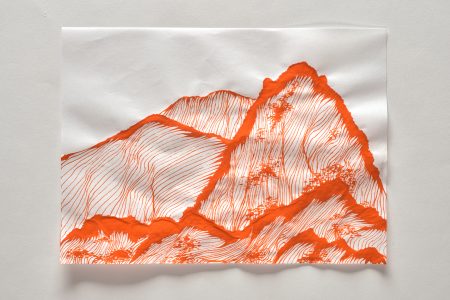

Cover Photo: Edouard Glissant, drawing for Hans Ulrich Obrist